Many of the bloodiest battles in World War I occurred along the Western Front. There was, however, another lesser-known combat theater that was as equally brutal and bloody: the Isonzo Front. This was the site of the Battles of the Isonzo, which saw more than one million casualties over two years of fighting.

Overview of the Battles of the Isonzo

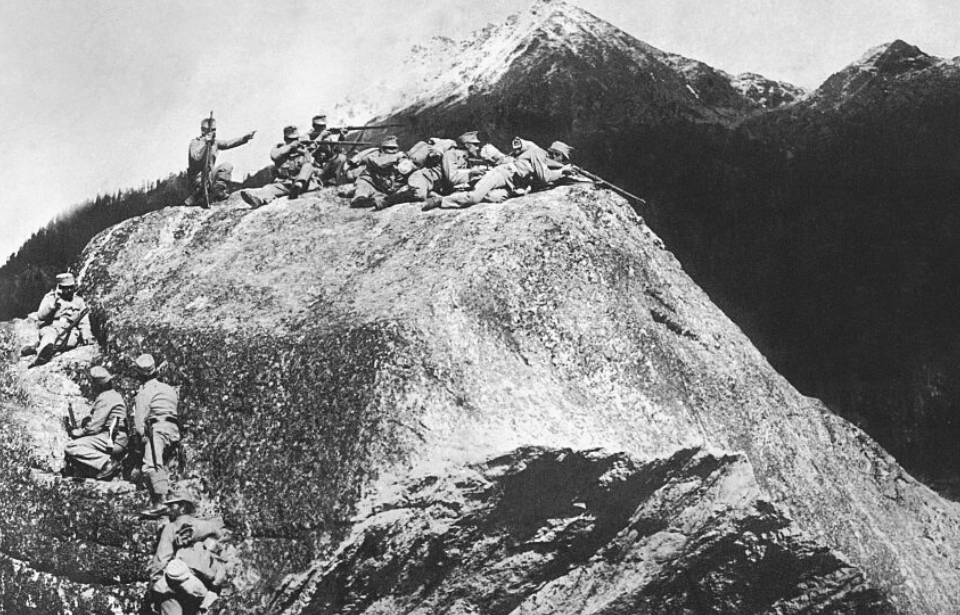

The Battles of the Isonzo were a series of 12 battles fought between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian armies along the border of what today is Slovenia. Lined with rugged peaks, the Austro-Hungarian forces had fortified the surrounding mountains before Italy officially entered the war.

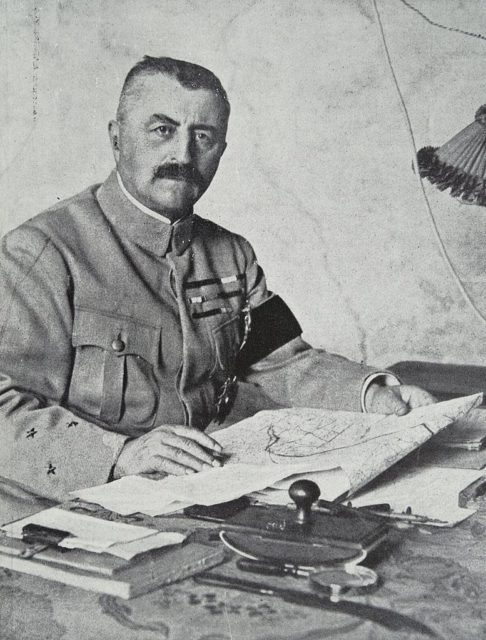

Italy set its sights on Austria-Hungary following the 1915 Treaty of London, which promised the country territories belonging to the Empire. Led by Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna, the Italians planned to seize Ljubljana. The first attack came on June 23, 1915. Despite their efforts and having more soldiers (ratio of 2:1), the Italian Army failed to secure a victory against the heavily-fortified Austro-Hungarian forces.

Cadorna believed the best location to launch an attack was the lower end of the Isonzo River, but he also saw a potential opportunity by striking north, to avoid the mountains altogether. Following the initial attack, the Italians tried to gain ground over several other offensives, and while they managed to penetrate a few miles, the Austro-Hungarian forces inflicted heavy losses.

It was clear the only way to succeed was for the Italian Army to take out positions in the mountains. However, at the same time, they had to cross the Isonzo River if they wanted to neutralize the Austro-Hungarian defenses – a dilemma Italy’s forces would never overcome.

Even with a better strategy, the next three battles throughout the autumn of 1916 were marred by the fortresses of the Austro-Hungarian-controlled mountains. As the fight for the Isonzo continued, countless resources were poured into what many could argue was a seemingly pointless conflict.

Mounting casualties

The casualties of the Battles of the Isonzo were horrific. Some 645,000 Italian soldiers were killed, accounting for roughly half of Italian military casualties throughout the First World War. The Austro-Hungarians suffered 450,000, for an overall total of around 1.2 million casualties – and that was prior to the final battle.

According to reports, the final battle, also known as the Battle of Caporetto, resulted in around 305,000 Italian casualties and 70,000 on the Austro-Hungarian side.

The first eleven Battles of the Isonzo

First Battle – June 23-July 7, 1915: Cadorna, a firm believer in the benefits of the campaign in Austria-Hungary, launched the first attack. The battle lasted 14 days, and, as aforementioned, the Italians were fought back by the Austro-Hungarians. The Italians were ultimately defeated.

Fourth Battle — November 10-December 2, 1915: The Italian Second Army attempted to occupy Gorizia. They successfully captured the nearby area of Oslavia and San Floriano del Collio, but failed to take their initial target. At the same time, the Italian Third Army launched a series of attacks, but these failed to bring about any significant gains.

Fifth Battle – March 9-17, 1916: The Second and Third Italian Armies once again attempted to take Gorizia, in order to reach the Tolmin Bridgehead. Though the battle was less bloody than those previous, Gorizia still remained free of Italian control.

Eighth Battle – October 10-12, 1916: With a similar goal to the previous, this offensive saw both sides struggle to achieve victory, as heavy Italian casualties forced the battle to be called off. They suffered between 50,000 and 60,000 casualties, while the Austro-Hungarian forces saw 38,000.

Ninth Battle – November 1-4, 1916: Now positioned in the Soča River Valley, the Italian Army tried to advance further inland, but were, again, met with heavy Austro-Hungarian resistance.

The twelfth and final Battle of the Isonzo

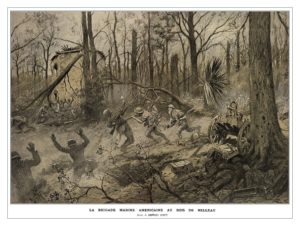

The twelfth Battle of the Isonzo was one of the most sweeping successes of the war. Austro-Hungarian and German forces collaborated and broke through the Italian line along the northern end of the Isonzo, surprising the enemy. By the afternoon of October 24, 1917, the Italians were exhausted and overwhelmed by the Austrian offensive attack; the troops threw down their weapons as Austrians rushed over the Isonzo River to claim Caporetto.

The Italians retreated toward the Piave River, where they established a position by the middle of November. It’s known as one of the worst losses in Italian history.

At the end of the Battles of the Isonzo, both sides had suffered massive losses, with very little accomplished. The fighting triggered violent anti-war protests throughout Italy, and Cadorna was forced to resign from his role. A new Italian strategy was put in place by Gen. Armando Diaz, who transformed Italy’s role in the war. By shifting from offensive campaigns to defensive ones, the country grew to be a resourceful aid to the Allied forces for the remainder of the war.

Ernest Hemingway’s famed novel, A Farewell to Arms, was somewhat inspired by the bloody Battles of the Isonzo. The book follows the first-person account of an American lieutenant serving in the Ambulance Corps of the Italian Army. Hemingway drew from his own experiences as an ambulance driver along the Italian Front during the Great War.