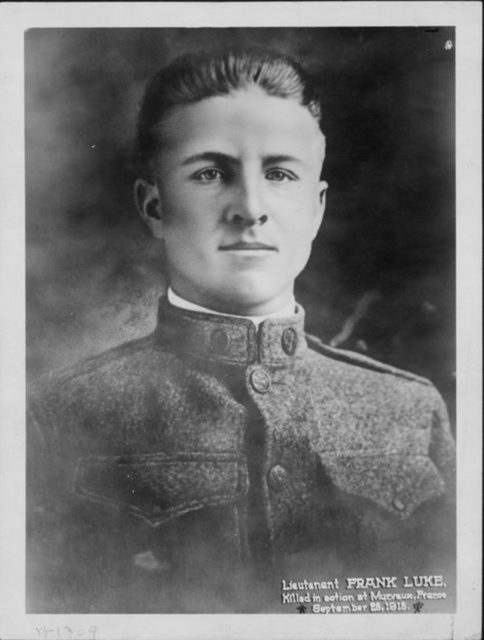

While dogfights first occurred during the Mexican Revolution, it wasn’t until the First World War that they became widespread. Upon returning home from service, pilots with the Aviation Section, US Signal Corps and the US Army Air Service were treated like heroes. Sadly, not all of them came back, including Frank Luke, a dashing and talented pilot who racked up an astonishing record before being shot down over France.

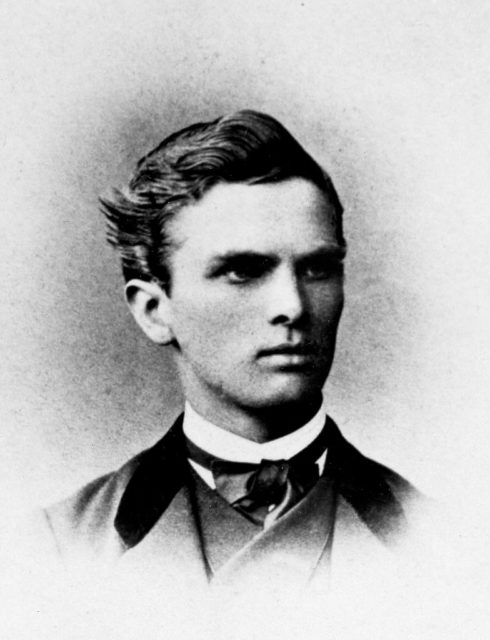

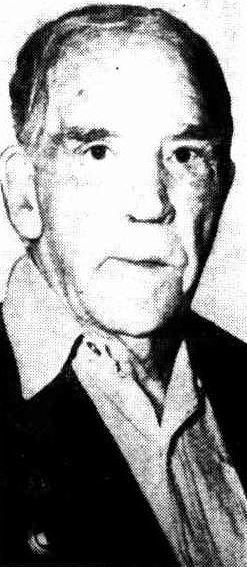

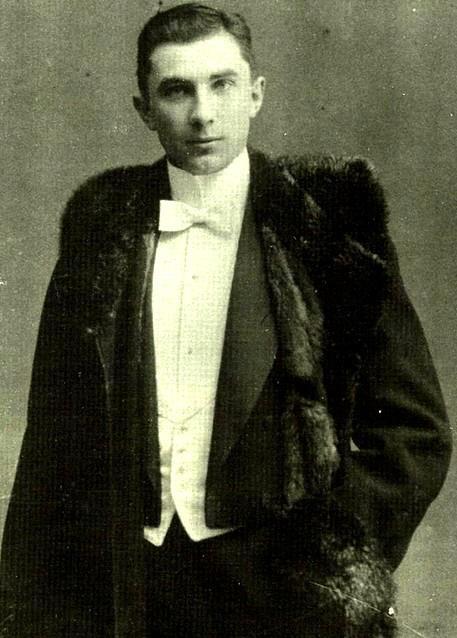

Frank Luke excelled as an athlete in his youth

Frank Luke was born in May 1897 in Phoenix, Arizona Territory as the fifth of nine children. While growing up, he was a star athlete, playing basketball and football, captaining his school’s track team, and participating in bare-knuckle boxing. He also worked in copper mines to help support his family.

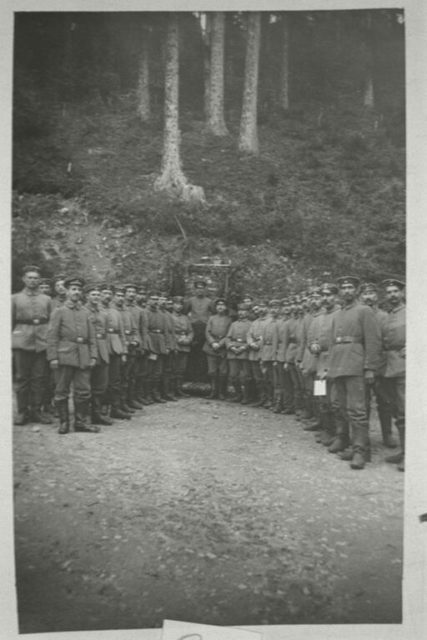

Luke enlisted with the Aviation Section, US Signal Corps in September 1917, months after the United States entered the First World War. After training in Texas and California, he was deployed to France with the rank of second lieutenant, where he underwent further training before being assigned to the 1st Pursuit Group, 27th Aero Squadron, which today is known as the US Air Force’s 27th Fighter Squadron, operating out of Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Virginia.

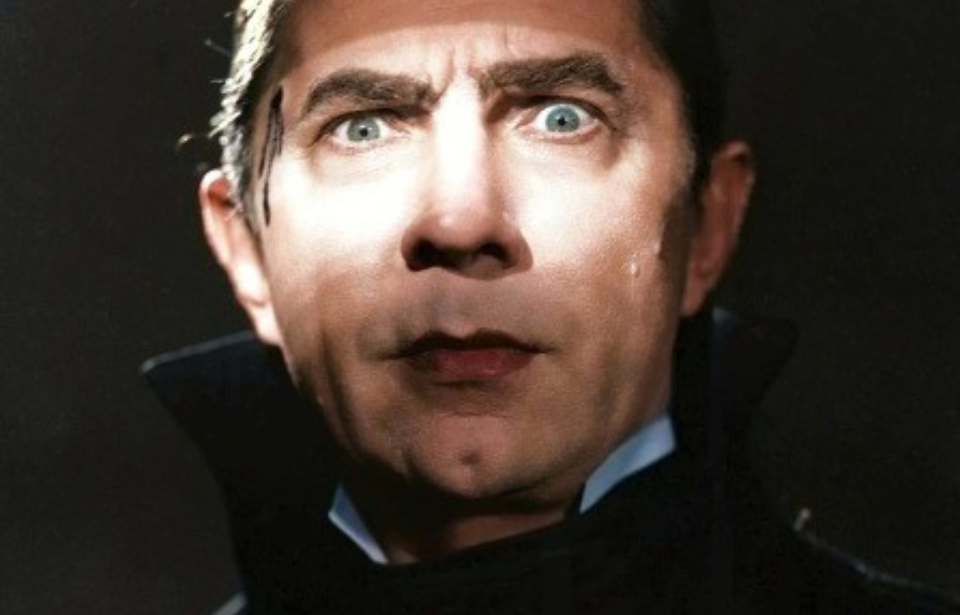

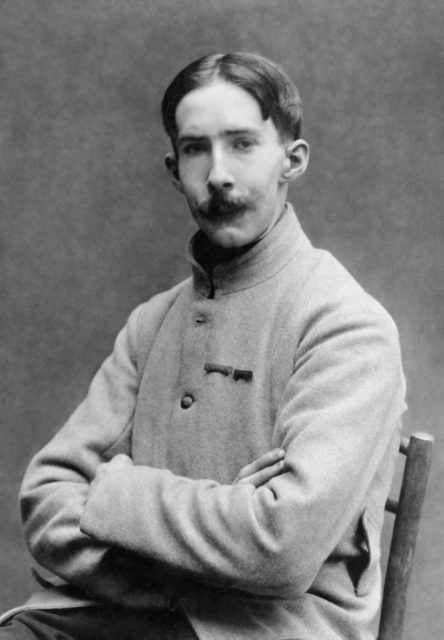

Frank Luke proved himself to be a remarkable pilot

Upon taking to the air, Frank Luke’s talent was immediately recognized, despite only flying in Europe for 17 days before his death. His commander, Maj. H.E. Hartney, later said of him:

“No one had the sheer contemptuous courage that boy possessed. He was an excellent pilot and probably the best flying marksman on the Western Front. We had any number of expert pilots and there was no shortage of good shots, but the perfect combination, like the perfect specimen of anything in the world, was scarce. Frank Luke was the perfect combination.”

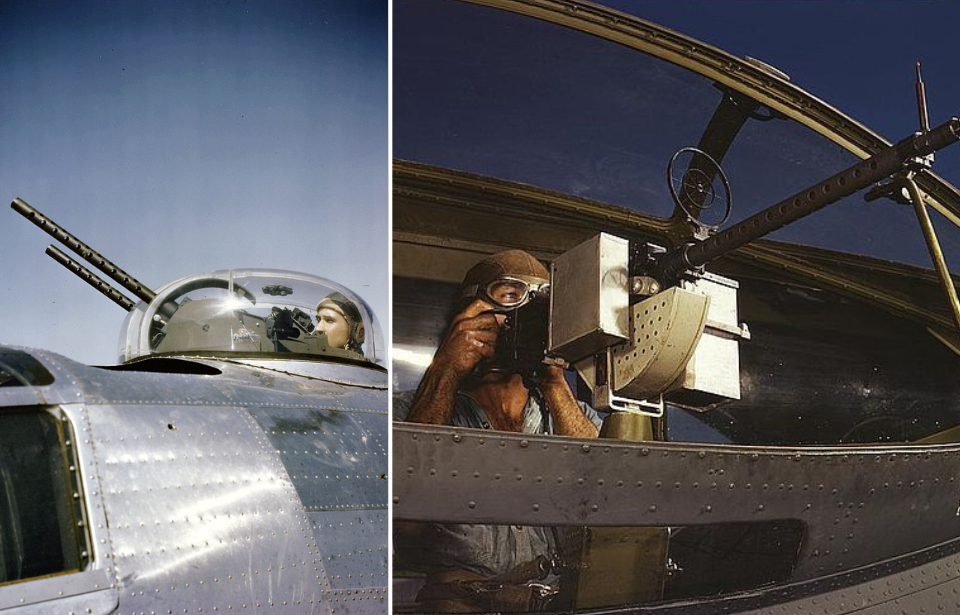

Observation balloons and dangerous missions

Throughout World War I, the German Army heavily relied on observational helium balloons. They were critical to the trench warfare that was occurring on the Western Front, as they allowed the Germans to see deep behind enemy lines. Given their importance, they were often protected by both anti-aircraft weaponry and a fleet of pursuit aircraft.

The American forces were eager to destroy these balloons. Despite the danger, Frank Luke and fellow pilot Lt. Joseph Frank “Fritz” Wehner regularly volunteered to take on the missions, with the former attacking the balloons and the latter serving as protective cover. Between September 12-28, 1918, the second lieutenant took out 14 balloons. In addition, he shot down four German aircraft, earning him the title of the “Arizona Balloon Buster.”

Frank Luke was shot down over France

Frank Luke’s final mission came in the early days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. On September 29, 1918, he took off looking to shoot down additional German observation balloons, having experienced success the previous day.

Luke had destroyed three balloons near Dun-sur-Meuse when he was struck by a bullet fired from a machine gun position on a nearby hill. It entered his shoulder, causing him to enter a tailspin toward the ground. Despite what was happening, the pilot strafed a group of German soldiers positioned beneath him.

Recipient of the Medal of Honor

Following his death, Frank Luke was awarded the Medal of Honor, which his family donated to the National Museum of the US Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, and posthumously promoted to the rank of first lieutenant. His additional decorations included the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Aero Club Medal for Bravery and the Italian War Cross. He was also named the nation’s greatest air hero by the American Society for the Promotion of Aviation in 1930.