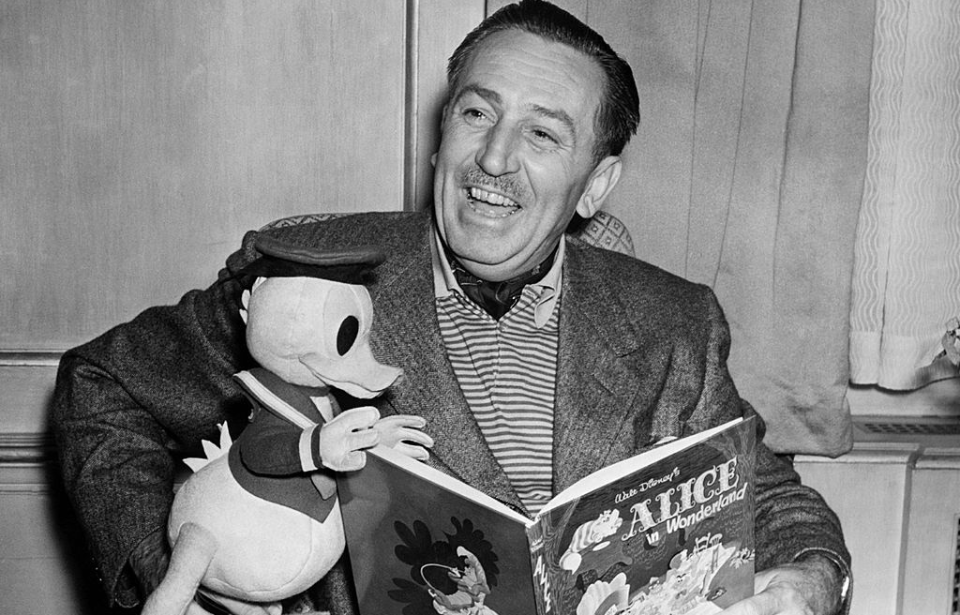

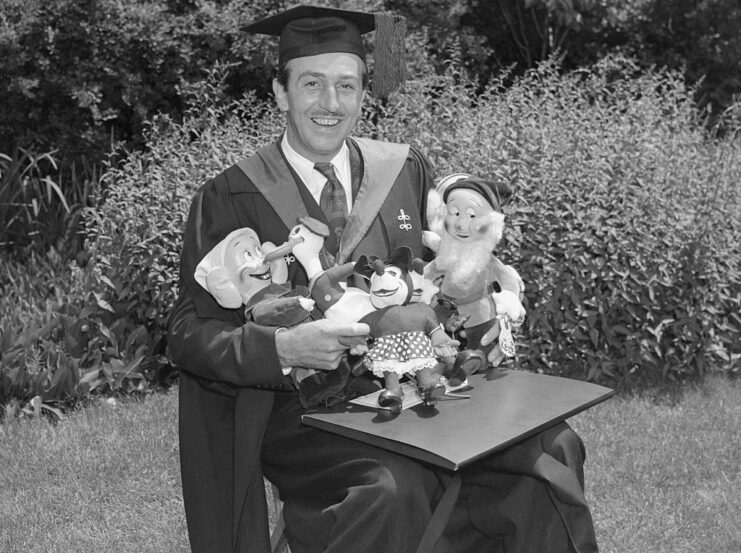

Growing up, Walt Disney had a passion for drawing. He pursued this as he matured, turning sketching into not just a career, but the biggest animation studio in the world. Disney had other passions, too, and one of those was serving his country in times of war. Unfortunately, he was either too young or too old to enlist during World War I and II, meaning he had to find other ways to contribute to the war effort.

Walt Disney’s early life

Walter “Walt” Disney was born on December 5, 1901 in Chicago, Illinois. In 1906, his family moved to Marceline, Missouri, where he spent his younger years developing his initial interest in art. While in Missouri, he received a commission to draw the horse of a retired neighborhood doctor, sparking his knack for drawing.

Disney’s father, Elias, had purchased a subscription to the Appeal to Reason newspaper, which the youngster used to practice his skills; he’d copy the front-page illustrations. Branching out and experimenting with different art mediums, Disney also tried his hand at watercolors and crayons.

Trying to enlist while underage

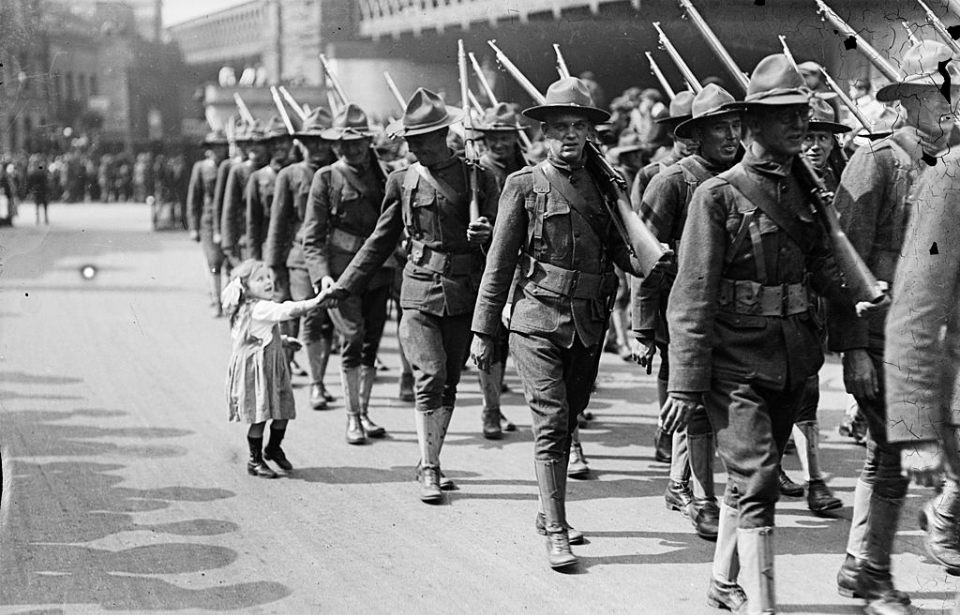

Walt Disney was inspired at a young age to serve his country. His older brother, Roy, enlisted in the US Navy in June 1917, which made Disney want to join the war effort even more. “He looked so swell in that sailor uniform,” he once recalled. “So I wanted to join him.” His two other older brothers, Ray and Herbert, also joined the US Army, serving as part of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

In an attempt to serve in WWI, a 16-year-old Disney tried to drop out of school and enlist in the Army (some sources say Navy). Unfortunately for him, he was rejected for being underage. Next, he and a friend attempted to join the Canadian Armed Forces, but his pal, Russell Maas, was rejected due to poor eyesight and Disney didn’t want to serve without him.

Undiscouraged, the young Disney forged the date of his birth on his birth certificate, so it looked like he was of age to join the Red Cross. The organization accepted him in September 1918, and he was trained as an ambulance driver.

World War I was over before Walt Disney arrived in France

Training for the Red Cross Ambulance Corps took place at Camp Scott, a temporary encampment at an old amusement park near the University of Chicago. To learn how to repair the ambulances, if needed, and drive on rough terrain, mechanics of the Yellow Cab Company spent weeks instructing the recruits. After this, they were subjected to two weeks of military training.

When Disney was sent to France in November 1918, the armistice had already been signed. Despite this, he made the most of his time overseas, explaining to his daughter, Diana, “The things I did during those eleven months I was overseas added up to a lifetime of experience. It was such a valuable experience that I feel that if we have to send our boys into the Army we should send them even younger than we do. I know being on my own at an early age has made me more self-reliant.”

Was Walt Disney dishonorably discharged?

A rumor has long circulated that Walt Disney was dishonorably discharged. However, this can’t be true, as he never served in the US military. He himself explained what sparked the story.

“It was in February… they sent me with a white truck,” he later recalled. “I was the driver and I had a helper. A white truck loaded with beans and sugar to the devastated area in Soissons. Well, I went out of Paris and it started to snow. I got up part way and I burned out a bearing on the truck, close to a watchman’s shed…

Offering support during World War II

Walt Disney was too old to serve in the Second World War, but he still did what he could to support the war effort. “Tomorrow will be better for as long as America keeps alive the ideals of freedom and a better life,” he once said of the conflict. To encourage these ideals, he partnered with the US military to create short films to boost morale, both at home and overseas.

During WWII, long after Disney Studios had been established, he formed the Walt Disney Training Films Unit, committing 90 percent of his workforce to developing instructional and propaganda films. Working with Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., he created the Donald Duck short film, The Spirit of ’43, which encouraged Americans to purchase war bonds.