Buried in the sand for a millennium: Africas roman ghost city

While the whole city often does not vanish, the Roman colony of Thamugadi was established in the North African province of Mumidia by Emperor Traian about 100 A.D., the city, also known as Timgad or Tamugas.

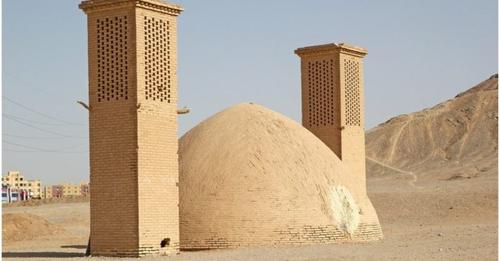

Home to Veterans of the Third Augustan Legion, Thamugadi flourished for hundreds of years, becoming prosperous and thus an attractive target for raiders. After a Vandal invasion in 430, repeated attacks weakened the city, which never fully recovered and was abandoned during the 700s.

The desert sands swept in and buried Thamugadi. One thousand years would pass before the city received a visit from a team of explorers led by a maverick Scotsman in the 1700s.

Originally founded by Emperor Trajan in 100 AD and built as a retirement colony for soldiers living nearby, within a few generations of its birth, the outpost had expanded to over 10,000 residents of both Roman, African, as well as Berber descent.

Most of them would likely never even have seen Rome before, but Timgad invested heavily in high culture and Roman identity, despite being thousands of kilometers from the Italian city itself.

The extension of Roman citizenship to non-Romans was a carefully planned strategy of the Empire – it knew it worked better by bringing people in than by keeping them out.

In return for their loyalty, local elites were given a stake in the great and powerful Empire, benefitted from its protection and legal system, not to mention, its modern urban amenities such as Roman bath houses, theatres and a fancy public library…

Timgad, also known as Thamugadi in old Berber, is home to a very rare example of a surviving public library from the Roman world.

Built-in the 2nd century, the library would have housed manuscripts relating to religion, military history, and good governance.

These would have been rolled up and stored in wooden scroll cases, placed in shelves separated by ornate columns. The shelves can still be seen standing in the midst of the town ruins, today a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a monument to culture.

The remains of as many as 14 baths have survived and a mosaic portraying Roman flip-flops was found at the entrance of a house in Timgad dating back to the 1st or 2nd century, with the inscription “BENE LAVA” which translates to ‘wash well’.

This mosaic, along with a collection of more than 200 others found in Timgad, is held inside a museum at the entrance of the site.

Other surviving landmarks include a 12 m high triumphal arch made of sandstone, a 3,500-seat theater is in good condition and a basilica where a large, hexagonal, 3-step immersion baptismal font richly decorated with mosaics was uncovered in the 1930s.

You can imagine the excitement of Scottish explorer James Bruce when he reached the city ruins in 1765, the first European to visit the site in centuries. Still largely buried then, he called it “a small town, but full of elegant buildings.” Clearing away the sand with his bare hands, Bruce and his fellow travellers uncovered several sculptures of Emperor Antoninus Pius, Hadrian’s successor.

Unable to take photographs in 1765, and without the means to take the sculptures with them, they reburied them in the sand and continued on Bruce’s original quest to find the source of the Blue Nile.

Upon his return to Great Britain, his claims of what he’d found were met with skepticism. Offended by the suspicion with which his story was received, James Bruce retired soon after and there would be no further investigation of the lost city for another hundred years.

Step forward Sir Robert Playfair, British consul-general in Algeria, who, inspired by James Bruce’s travel journal which detailed his findings in Timgad, went in search of the site. In his book, Travels in the Footsteps of Bruce in Algeria and Tunis, Playfair describes in detail what he found in the desolate and austere surroundings of the treeless desert plain.

“The whole of this district is of the deepest interest to the student of pre-historic archaeology … we left Timegad not without considerable regret that we could not afford to spend a longer time there. We would fain have made some excavations as there is no more promising a field for antiquarian research.”

Just a few years later, French colonists took control of the site in 1881, and began a large-scale excavation, which continued until Algeria gained independence from France in 1959.

“These hills are covered with countless numbers of the most interesting megalithic remains,” wrote Playfair in 1877.