A former Topgun instructor describes a typical combat training mission during his time at the Navy Fighter Weapons School.

In September 1982 I was one of eight students being briefed in a classroom at the Navy Fighter Weapons School at Naval Air Station Miramar for a series of flights over southern Arizona, part of the five-week Topgun class. We were four pilots and four radar intercept officers (the RIOs included me) from four different squadrons. When the instructor was done, we headed back to our hangars and manned-up our F-14A Tomcats.

We took off in pairs, for the day’s scenario was two fighters versus an unknown number of adversaries, which showed up on the flight schedule as 2vUNK. The first number always referred to the fighters (good guys), while the second referred to the bandits (bad guys). Each run would begin with about 30 miles of separation between the opposing parties. The fighters would run a radar intercept against the bandits and launch simulated missiles along the way if shot criteria were met. When we intercepted the bandits, we would engage any that remained in a swirling dogfight. As F-14 pilots and RIOs we were confident in our abilities and looked forward to the day’s challenges, even though our opponents were highly skilled, wily Topgun instructors.

Grumman F-14s had been part of Topgun since they joined operational Navy squadrons in 1974. Over the next few years they displaced the legendary McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II as the Navy’s frontline fighter, but F-4s hadn’t completely disappeared. In addition to the four Navy Tomcats in my Topgun class, four Marine Corps Phantoms filled the remaining openings in the then-standard eight-plane class. But we mostly operated with our own species, mixing aircraft types on a few flights as the syllabus progressed from 1v1 to 8vUNK in 28 flights over the five weeks.

While the F-4 had earned an impressive reputation in combat, partly as a result of training conducted by Topgun and similar programs during the Vietnam War, the F-14 brought many useful improvements to the tactical air combat arena. In terms of aerodynamics, the F-14’s swing wings maintained the optimum angle as the Mach number changed, while the “tunnel” area between the engines provided substantial lift, both of which increased the Tomcat’s turning ability compared to its predecessor’s. Cockpit switchology was more logical than in previous fighters, and the large canopy provided the crew with excellent visibility all around. The Hughes AWG-9 radar and weapons control system enabled F-14s to detect and track targets at long range, track multiple targets and launch radar-guided missiles at targets below our altitude, known as “look-down, shoot-down.” Though common today, these were important improvements when the F-14 was introduced.

I didn’t think about these innovations that morning as I orbited 15 miles east of the Marine Corps Air Station at Yuma, Ariz. I was flying with Lieutenant Sandy Winnefeld, call sign “Jaws,” a talented pilot and squadron mate in Fighter Squadron 24 (VF-24). We hadn’t flown together much, but a few warmup hops and some frank discussions with Topgun veterans in the squadron helped us to be ready when the course started.

“Boomer” and “Jake,” Lieutenants John Stufflebeem and Steve Jacobsmeyer, were our wingmen. They were the pilot and RIO, respectively, of an F-14 from sister squadron VF-211. Our squadrons were assigned to the same carrier, and in standard Topgun fashion we were wingmen throughout the class. In the “2v…” phase, we flew with Boomer and Jake on every flight, taking turns as flight lead while the other plane was the wingman. Once an intercept developed, we could switch tactical lead and wingman roles if necessary. We briefed the ground rules for these switches, and used radio calls to accomplish them. After a few flights we operated well as a team.

Crusing above the Pacific, “Bio” Baranek enjoys the 360-degree view afforded by the Grumman F-14s cockpit. The Tomcat was the first U.S. fighter in decades to offer such all-around visibility. (Dave Baranek)

Crusing above the Pacific, “Bio” Baranek enjoys the 360-degree view afforded by the Grumman F-14s cockpit. The Tomcat was the first U.S. fighter in decades to offer such all-around visibility. (Dave Baranek)

We had completed F-14 training within months of each other, and had roughly 1½ years in our fleet squadrons at this point. All of us had flown multi-aircraft missions, but few of those had the intensity we experienced in Topgun, which was really a “graduate course” in fighter employment. As the scenarios evolved, I expanded my sphere of tactical concern outward from my own cockpit to encompass multiple aircraft and consider how my fight affected our assigned mission. Thanks to Topgun’s intense debriefs and a no-holds-barred attitude shared by Jaws, Boomer and Jake, my skill as an RIO increased rapidly from the first day.

My own call sign was “Bio,” though for a week or so it was “Bionic,” since that rhymes with my last name. One of my F-14 instructors, Lieutenant Steve “Superman” Jones, encouraged me to go with that call sign when I was an ensign, but it didn’t sound good on the radio, and I wasn’t very “bionic” anyway. So my first pilot in VF-24 shortened it to Bio, which stuck.

Our 2vUNK scenario was one of the most realistic, because the basic unit for combat employment of Navy fighters is a section (two fighters) composed of lead and wingman. The value of a second fighter was borne out repeatedly, and the Navy almost never assigned a single fighter to a combat mission. If we started out as a division of four fighters, we could easily split into two sections.

On the bandit side, in the real world you rarely knew for sure how many you were actually facing, so it was always good to think there were an “unknown” number of bandits. Despite the quality of E-2 Hawkeye, E-3 Sentry AWACS or shipboard radar control, despite the fighters’ ability to sanitize airspace and kill enemy aircraft before the merge, additional enemy fighters could show up over hostile territory at almost any time. Focusing on killing those you see is a good way to be killed by those you don’t. One of the worst times an unknown could show up would be while the fighters were running an intercept—with RIOs looking at their radars, pilots setting up a tactical formation, everyone checking switches in their cockpits, communicating with the radar controller and thinking 15 to 30 miles ahead. Topgun wanted to give us the most challenging training possible, so it had the option to use a“Wild Card,” a single bandit that could jump the fighters any time after the fight’s-on call.

Crews were always briefed when we were susceptible to being jumped by a Wild Card, because otherwise the appearance of an unexpected aircraft would be cause to terminate the run. And even when we weren’t actually jumped, just checking for the Wild Card added to our workload.

Our Topgun opponents were flying Northrop F-5E and F-5F Tiger IIs and McDonnell Douglas A-4F Skyhawks. On paper the F-14 bested both aircraft in most measures of performance, even though it was much larger than either of them. But their small size and agility helped both types challenge the Navy’s frontline fighters. Moreover, the experience of their Topgun pilots was a huge factor and one of the school’s major teaching points: Aircrew training and performance are frequently the deciding factor in aerial combat.

Led by a two-seat Northrop F-5F, three single seat F-5E Tiger IIs head out for an early morning mission—to give Topgun students a run for their money over Southern California. (Dave Baranek)

Led by a two-seat Northrop F-5F, three single seat F-5E Tiger IIs head out for an early morning mission—to give Topgun students a run for their money over Southern California. (Dave Baranek)

For this Wednesday morning run—halfway through the five-week program—all Topgun aircraft were simulating MiG-21s with simple heat-seeking missiles that had to be fired from the rear quarter so they could track our exhaust heat. That gave the F-14s a decided advantage during the intercept, but would still be a challenge once we engaged the bandits.

Flying in loose formation at 22,000 feet and about 220 knots indicated airspeed, we waited for the first two F-14s to finish so we could take our turn on the range. Rather than just kill time waiting, we switched the front-seat radios in both jets to listen to the other section. We heard the fighters ahead of us run intercepts, call missile shots and engage at the merge. It did not go well. Since it played out just moments before we were to enter the same arena, however, this helped us prepare mentally and gave us fresh incentive to remain calm and professional.

The other section knocked off their last fight and headed for Yuma to refuel and debrief. We reset our front-seat radios to our assigned frequency, and on the back-seat radio I called, “Topgun 3 and 4 ready for weapons checks.” We coordinated with our controller to verify that our TACTS pods were working. Each aircraft carried a small pod that linked us to the Tactical Aircrew Combat Training System, transmitting our position, speed, Gload and other information to ground stations where it was viewed in real time and recorded, making it a priceless aid for both real-time control and detailed debriefs. I thought TACTS was a cool gadget when I was first exposed to it, and the more I used it, the more I appreciated its value.

Our controller said, “Bandits on station, ready.” Having done this about two dozen times so far in Topgun, our section was ready so I replied, “Fighters are ready.”

The controller said, “Recorders on, fight’s on. Bandits 108 degrees at 36 miles, angels 22, headed northwest.” Angels 22—they were at an altitude of 22,000 feet. That would surely change during the run.

As we completed our left turn, Jake and I both slewed our radars to the limit of their scan volumes to point toward the threat. I was searching medium to high altitude, he was searching medium to low. For initial detection I used long-range automatic mode, and almost immediately saw initial radar contacts, so I said over the radio, “Jaws contact that call. Fighters steady one-zero-zero.” On a mission like this, we used the pilot’s call sign for our aircraft.

The hits on my radar were off a few degrees from the controller’s call, but it was close enough for the start of the intercept. My directive call to the pilots—fly a heading of 100 degrees—was more important than the target’s exact location at this point. This was something all RIOs are taught starting in Pensacola, but at Topgun it was hammered home for me. During the intercept, the lead RIO had to drive the fighters.

The radar placed a small symbol for the contact on the 9-inch scope between my knees. This was the tactical information display (TID). Jaws had a duplicate of the display, but he wasn’t looking at it. We’d talked about who looked where during the intercept, and at this point his attention was focused outside.

I took two seconds to look high over my left shoulder, then jerked my head to look high over my right, scanning for a Wild Card. He would be hard to see against the bright midday sun. Nothing up there. Jake was doing the same in his jet. I returned to my radar.

I noted bandit altitude, about the same as ours, and figured this would be a good time to switch the radar to a manual mode (pulse search) to try for a better sense of the number of bandits and their formation. I adjusted antenna elevation, then twisted other knobs to enhance the radar picture, actions that were essentially subconscious by then, given my 700 hours in the F-14. I leaned forward to squint at the small 4-inch detail data display (DDD) in front of my face. On the glowing green screen I saw black blobs representing mountains, and discerned several well defined black dots.

“Jaws, single group, 108 at 32,” I estimated over the radio. It was still early in the intercept, so I didn’t have to be too accurate. I reached up and switched back to the autotrack mode. I told Jaws about my radar mode switches. If I was having problems, he might suggest a solution, but this run was going fine so far.

Jake said, “Boomer same.” He saw the targets that the controller and I called, and had no additional bandits in his altitude block.

We were flying at about 350 knots, the bandits about the same. Every second we came almost 1,200 feet closer to each other. This was the slow part of the intercept.

It was now about 30 seconds after the fight’s-on call. “Jaws, 112 at 30, angels 22, heading west, speed 350.” Bearing, range, altitude, heading and speed. My radar was automatically tracking one of the targets and occasionally showed another symbol, but it couldn’t yet distinguish all the additional targets. Our heading was fine, so I didn’t need to give direction for a few seconds. We were headed roughly east (100 degrees), accelerating through 400 knots, with Boomer and Jake on our left side about 1½ miles away. Every few seconds I looked for a Wild Card.

On the intercom I told Jaws,“I see additional targets in pulse, but they’re just a gaggle.”

“Roger.”

I looked up and left again, then right, and called over the UHF radio, “Jaws, hard right, tally, right five high!” I’d spotted a bandit about 10,000 feet above us, just beginning his attack—a Wild Card.

Jaws added power and pulled our jet into a level 4-G turn to the right, abandoning the intercept to deal with the immediate threat. Boomer started to go nose-low so both fighters were not in the same piece of sky. Four sets of eyeballs looked high and to the right.

After 30 to 40 degrees of turn, we heard over the radios, “Fighters continue.” That call came from the Wild Card pilot and meant we had seen him early enough to meet the training objective, so now we could turn our attention back to the intercept. Over the radio I immediately said, “Jaws, left, steady 110.” Estimating we were about 25 miles from the bandits, I wanted to get them on radar and reassess. The AWG-9 lost the target in the turn but displayed an estimated location. This agreed with my mental plot, so I ensured my radar was looking in the right place.

In just a few seconds the target reappeared, and now the radar broke out additional targets.“Jaws, single group, 115 at 22 miles, come left 090. They’re at angels 18, let’s go down.”

Jake answered, “Boomer, second group in eight-mile trail.”

Aside from its relatively slow roll rate, the F-14 was remarkably maneuverable for a 60,000-pound fighter with a 62-foot length and fully extended wingspan of 64 feet. (Dave Baranek)

Aside from its relatively slow roll rate, the F-14 was remarkably maneuverable for a 60,000-pound fighter with a 62-foot length and fully extended wingspan of 64 feet. (Dave Baranek)

We immediately recognized this tactic from our classes. While we were dealing with the Wild Card, some bandits performed a tight delaying turn that put them a few miles behind the lead. This would complicate our decision-making: We couldn’t dogfight the first bandits, or the trailers would easily shoot us, but we couldn’t ignore the lead bandits either. If we could use the Tomcat’s vaunted AIM-54 Phoenix missile, we could each launch missiles at some targets, then attack the others with our other weapons. But in those days AIM-54s were “reserved” for defending the carrier against a Soviet bomber raid, so we had a real challenge—especially since we were required to visually identify all aircraft before shooting.

As we had planned, Jake now focused his radar on the second group.

We were now inside of 20 miles to the lead group. Jaws descended to 16,000 feet and leveled off. I switched again to the manual radar mode and got an accurate look at the bandit formation. Both the fighters and the bandits accelerated, so we were now approaching each other at one mile every four seconds. On the radio I described the bandit formation, “Jaws, lead group is lined-out right, 18 miles, angels 18.”

Jake said, “Boomer, trailers at 25 miles.” It sounds like a long distance, but I knew things would happen fast in the next minute and was feeling the excitement.

I switched back to auto-track mode, and adjusted the scale of my display. The radar took a few sweeps to process information. Now we were about 13 miles from the lead group. On the intercom I said, “Jaws, look at the TID.” For most of the intercept to this point Jaws had been looking outside the aircraft. When we had less than 15 miles to the merge I set up a picture on the display that he could see, then told him when to look.

This was his cue to say, “Boomer is at left eight low,” using the common clock code.

Jaws looked in to get the tactical picture. I looked out to locate our wingman. He said, “Got it,” and I said, “Visual,” so we both accomplished what we intended.

I turned to the radar again and took a radar lock on the lead bandit, which would allow us to shoot an AIM-7 Sparrow missile. Once I saw the two small green lights indicating a good lock, I said over the radio, “Jaws, locked lead, 10 miles, lined-out right.”

Jake said, “Boomer, trailers at 16 miles, angels 15, line-abreast.” So the second group had sped up a little, and they were a little below us.

Jaws turned our fighter to the right to put the targets on the nose. He looked through the head-up display on his windscreen, and a green diamond showed target location based on our radar lock. Jaws had good vision and called, “Speck in the diamond.” This let everyone know he could see something where the bandits were supposed to be, which was good.

I divided my attention between ensuring the radar lock stayed good, checking Boomer’s position, checking fuel and making notes for the debrief. If the radar hiccupped, I could manually get another lock, but that didn’t happen on this run. I didn’t write a lot of notes during intercepts, but the Topgun debrief was always in the back of my mind.

“Fox One, lead A-4, 18,000 feet.” Jaws squeezed the trigger on his stick, and a tone indicated that the simulated AIM-7 shot registered on the TACTS instrumentation. He had identified the aircraft type and altitude to show he was not just taking a wild shot.

In the next 30 seconds things happened fast, and there was a lot of information to process. Boomer made a radio call that he saw both bandits in the lead group. Jake made a radio call about the trail group; he had a radar lock. I updated Jaws on Boomer’s position (9 o’clock low, one mile). The bandit we shot was called dead by the TACTS controller. Jaws selected a Sidewinder heat-seeking missile, got a tone and called a shot on the second bandit in the lead group. That one was also a kill; the lead group was gone. Jaws gave Boomer the lead to get us to the trailers, only eight miles away now. From looking out and forward to acquire the bandits, I went back to the radar and took a lock on the second bandit of the trail group.

“Fox One, northern F-5, 15,000 feet.” Boomer had identified and shot one of the trailing bandits. On his call the entire formation was considered hostile, so Jaws also launched a missile: “Fox One, southern bandit that group.”

The TACTS controller announced both of those bandits killed, then said, “Knock it off, knock it off. Jaws, knock it off. Boomer, knock it off, state 10.8.”

So there had been four bandits downrange, and we were awarded kills for all of our missile shots. A great way to start a day of flying! We flew back to our holding point and set up for the next run.

On the second run we did not have a Wild Card, but that aircraft flew with the other bandits to present us with a 2v5. We also did not kill all the bandits before the merge, so we had some great engaged time. We then flew a third engagement, a short setup of about 20 miles, before landing at Yuma to debrief, turn the jets around and brief for an afternoon go. On later flights Topgun would simulate bandits armed with radar-guided missiles, presenting us with a more challenging intercept.

I rarely thought about the specific elements of the F-14 that made us so capable in both the intercept and engaged portions of air-to-air combat. They were all things that I had been trained to use, and my expertise in employing the total system was demanded. In looking back and comparing the systems, capabilities and threats from 1982 to those of today, however, it is interesting to think how much has changed. In general, fighters worldwide now have greater maneuverability and increased engine thrust compared to aircraft then in service. Avionics and air-to-air missiles of friendly and threat forces have also seen significant advances.

Yet a common element links combat aviators of all eras: The aircrew makes the difference. The training, skill and performance of the pilot and additional crew are often the deciding factors in an engagement. Topgun and similar programs have always realized this, and they continue to prove its validity and relevance in aerial warfare.

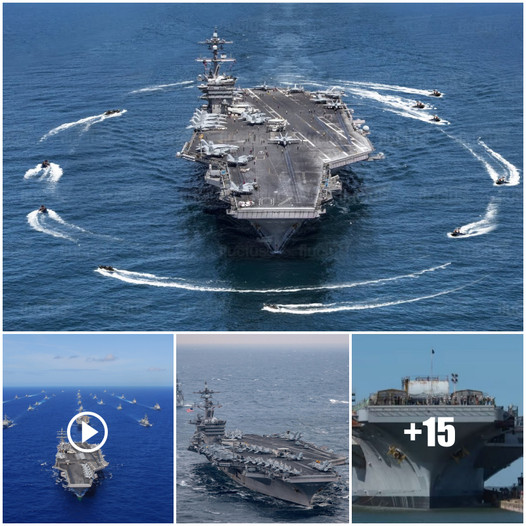

BlueBarronPhoto/Shutterstock

BlueBarronPhoto/Shutterstock

Crusing above the Pacific, “Bio” Baranek enjoys the 360-degree view afforded by the Grumman F-14s cockpit. The Tomcat was the first U.S. fighter in decades to offer such all-around visibility. (Dave Baranek)

Crusing above the Pacific, “Bio” Baranek enjoys the 360-degree view afforded by the Grumman F-14s cockpit. The Tomcat was the first U.S. fighter in decades to offer such all-around visibility. (Dave Baranek) Led by a two-seat Northrop F-5F, three single seat F-5E Tiger IIs head out for an early morning mission—to give Topgun students a run for their money over Southern California. (Dave Baranek)

Led by a two-seat Northrop F-5F, three single seat F-5E Tiger IIs head out for an early morning mission—to give Topgun students a run for their money over Southern California. (Dave Baranek) Aside from its relatively slow roll rate, the F-14 was remarkably maneuverable for a 60,000-pound fighter with a 62-foot length and fully extended wingspan of 64 feet. (Dave Baranek)

Aside from its relatively slow roll rate, the F-14 was remarkably maneuverable for a 60,000-pound fighter with a 62-foot length and fully extended wingspan of 64 feet. (Dave Baranek)