Death is an inevitable part of life. People are born, they live their lives, and then they die. This has always been the case, and for now, at least, the unending cycle continues. However, throughout history, there have been those who sought to rebel against the natural order — and defy death itself.

The idea of immortality is nothing new. Since the earliest tales of humanity, the concept of living forever has remained a pervasive fixture, an unachievable goal that just so happens to make for enjoyable fantasy or science fiction.

But what if immortality was truly achievable? Could humanity grasp the unlimited potential of a life extended beyond its natural limitations? These are the questions the nine people on this list sought to answer. Of course, their various attempts at immortality did not pay off.

Qin Shi Huang, The Chinese Emperor Who Wanted To Live Forever

A portrait of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China.

More than 2,200 years ago, the first Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang began seeking a potion that would grant him immortality. The emperor even issued a nationwide call for his subjects to search for an elixir of life.

In 2002, 36,000 wooden strips with ancient calligraphy were found in an abandoned well in China’s Hunan province. A later study determined that some of the strips contained messages in response to Qin Shi Huang’s bizarre decree.

According to the Chinese outlet Xinhua, one of the messages stated that although villagers in Duxiang hadn’t yet discovered the desired potion, they would keep looking. Another strip suggested that an herb from a nearby mountain may help the emperor.

It’s believed that the emperor may have eventually resorted to consuming cinnabar, or mercury sulfide, in an effort to live longer. Ironically, that may be what killed him at the age of 49.

In fact, Qin Shi Huang’s death is perhaps what he is most famous for. In 1974, farmers stumbled across the emperor’s tomb — and the 8,000 life-sized terracotta warriors guarding it.

Pope Innocent VIII, The Supreme Pontiff Who Drank The Blood Of Children

A portrait of Pope Innocent VIII.

A common theme in many fictional stories about immortals is blood. Tales of vampires may be the best example of this: The monsters feed on the blood of their innocent victims to extend their own eternal lives.

As it turns out, the idea of drinking blood as a method of extending life isn’t completely fictional. Per a study published in Transfusion Medicine Reviews, one of the first instances of a blood transfusion may have occurred in 1492 — and the recipient was none other than Pope Innocent VIII.

It should be noted that, despite being a holy man, Pope Innocent VIII was not the sort of person his name would suggest. He sired several illegitimate children and was obsessed with money and power. In fact, the pope’s time in the Holy See was largely marked by an increase in immorality among the clergy.

As the pope aged, his health began to decline sharply. He suffered a stroke in 1488, and by 1492, he was nothing more than “an inert mass of flesh.”

Pope Innocent VIII recruited a Jewish physician to help save his life. According to various historical sources, the doctor took the blood of three young boys, killing all of them in the process. Some stories suggest that the blood was somehow infused into the pope’s veins — but most indicate that he drank it.

The boys’ lives were sacrificed for no reason, as Pope Innocent VIII died just days later, on July 25, 1492.

Diane De Poitiers, The Woman Who Drank Herself To Death — With Gold

Diane de Poitiers was a mistress of King Henry II of France.

A 16th-century French noblewoman, Diane de Poitiers held significant influence in the court of her lover, King Henry II. Her sway on Henry was stronger than that of his wife, Catherine de’ Medici. The king even gifted her the crown jewels and Château de Chenonceau, which the queen herself wanted.

Diane de Poitiers rarely used her influence over the king for matters of state, however. Rather, she exerted her power to gain material possessions and luxuries for herself, her friends, and her family.

Given her penchant for lavish items, it’s no surprise that de Poitiers went to extremes to maintain her beauty — and it may have killed her. According to Atlas Obscura, the noblewoman routinely drank gold chloride mixed with diethyl ether.

Though she lived to be 66, contemporary records state that she appeared forever young. French historian Brantôme wrote, “I believe that if this lady had lived another hundred years she would not have aged… in her face, so well-composed it was.”

The idea of drinking gold to retain one’s youth predated de Poitiers, of course. Even ancient Egyptians used “gold-water,” believing that because the metal didn’t corrode, it would bring longevity to those who ingested it.

However, when Diane de Poitiers’ grave was ultimately rediscovered centuries after her passing, researchers discovered high levels of gold in her hair. This indicates that she likely died of chronic intoxication due to her efforts to maintain her youthful appearance.

Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard, The Physiologist Who Believed Guinea Pig Testicles Would Grant Him Eternal Life

Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard was a successful physiologist but attracted controversy for his use of animal testes extracts.

Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard was always something of an outcast. A horribly depressed and withdrawn student of medicine, he often traveled as a means of escaping his less-than-ideal life. It is said that he crossed the Atlantic Ocean more than 60 times in the mid-1800s, setting sail whenever he experienced moments of sadness or difficulty, according to a study of his work in Brain: A Journal of Neurology..

Colleagues described Brown-Séquard as difficult and distractible yet energetic and full of grandiose plans. Unfortunately, he often fell into fantasies that made it nearly impossible for him to function normally.

One of his more eccentric ideas was that he could achieve anti-aging effects and sexual prowess using extracts from dog and guinea pig testes. Over a three-week period, he injected himself with these extracts and claimed that he noticed improvements in his concentration skills, his strength and endurance, and even his bowel habits.

Brown-Séquard had also previously infused his own blood into criminals who had been decapitated by a guillotine, ingested the vomit of cholera patients, and varnished his skin — only for his students to have to sand the varnish off when they found him unconscious.

So while Brown-Séquard’s work with guinea pig testicles was far from his most bizarre self-experiment, it was his most infamous. News of his hypothesis spread quickly, inviting harsh ridicule. Brown-Séquard’s reputation took a hit — and he died five years later, despite the supposedly anti-aging injections.

James Schafer, The 1920s Cult Leader Who Tried To Raise An Immortal Child

A photo of Baby Jean in a 1940 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Sometimes, people seek immortality not for themselves but for their cause. Enter James Schafer, the leader of a little-known cult called the Royal Fraternity of Master Metaphysicians.

Schafer founded the cult in the 1920s and referred to himself as its “Messenger.” He claimed the group was devoted to “the joyous work of helping others to help themselves,” according to TIME.

Schafer made a number of other wild claims, including that he could cause people or things that stood in his way to vanish. He also believed that death and illness were the result of negative thoughts.

In 1939, Schafer and his cult announced that they were going to achieve the impossible — by raising an immortal baby. The infant was a foster child named Jean Gauntt, whose mother reportedly lacked the financial means to care for her.

Baby Jean, as she came to be known, was never officially adopted by Schafer or anyone within his cult. Nevertheless, Schafer brought her to his Long Island mansion when she was just a few months old and strictly governed every aspect of her life.

He raised her under the belief that she should not be exposed to anything that would lead to “bad or destructive” thoughts. Schafer fed her a vegetarian diet void of alcohol, tobacco, coffee, tea, mustard, vinegar, and spices, all to prove that immortality “can actually be achieved, not as a ghost or spirit.”

James Schafer planned for Baby Jean to take over as the cult’s leader in the event of his death, but after just 15 months, the experiment came to an end when the child’s mother sued for custody.

Nicolas Flamel, The Alchemist Who Allegedly Found The Philosopher’s Stone

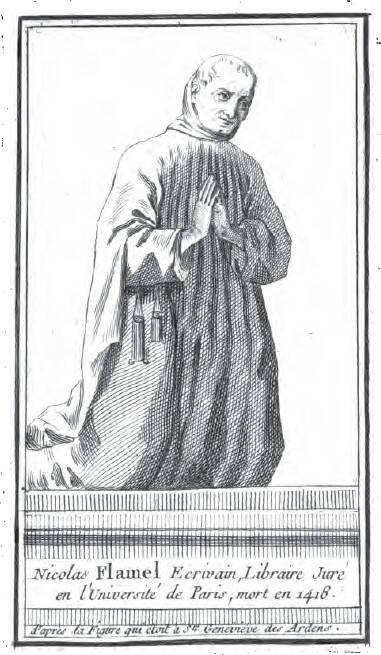

The real-life Nicolas Flamel, who served as inspiration for the character in Harry Potter.

The goal of all alchemists was ultimately to make gold out of more common elements. Of course, most of them were unaware that gold itself is an element and, therefore, impossible to create out of other substances — but that didn’t stop them from trying.

One of the most well-known alchemists was Nicolas Flamel, a man who allegedly claimed to have found the one missing ingredient needed in order to create gold: an elusive material known as the philosopher’s stone, also called the “elixir of life.”

According to Dr. Joe Schwarcz of McGill University, the largely incoherent writings that supposedly belonged to Flamel claimed that he discovered the philosopher’s stone on April 25, 1382, unlocking the key to transmutation — and to immortality.

These writings were later discovered by another alchemist named Vincenzo Cascariolo, who believed that he, like Flamel, could create the philosopher’s stone. There was just one problem.

Nicolas Flamel was indeed a real person, but he was not an alchemist at all. He was actually a 14th-century scribe who made a fortune speculating on real estate, and he used his wealth to help build hospitals and homes for the less fortunate.

But for some reason, books supposedly written by Flamel began to appear in the 16th century, well after he had passed. Some theorists speculate that Flamel did indeed discover the philosopher’s stone, became immortal, and faked his own death in the 14th century — but the facts suggest otherwise.

Still, many associate his name with the philosopher’s stone and the quest for immortality.

Alchemists who believed in the philosopher’s stone spent decades of their lives searching for the right combination of ingredients to create it. Of course, most of these efforts were in vain. Cascariolo was one of them — and for a moment, he believed he was on the right track.

Combining barite, powdered coal, and iron, Cascariolo produced a material that shone in the dark and could be reenergized by exposure to the sun. No, it was not the philosopher’s stone, but Cascariolo did create the world’s first glow-in-the-dark substance.

Alexander Bogdanov, The Soviet Genius Who Died Trying To Become Immortal

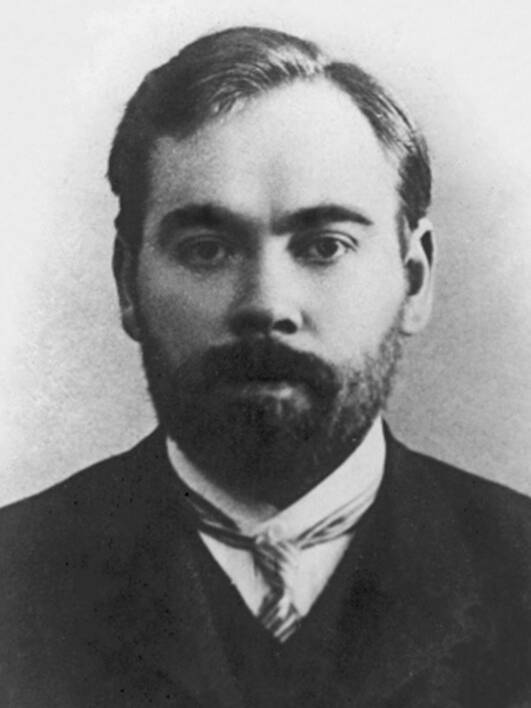

Alexander Bogdanov was a science fiction writer, poet, and hematologist.

Alexander Bogdanov was a man of many talents. A highly intelligent doctor who served in World War I, Bogdanov also wrote a series of essays on the politics of war economies in which he made several predictions about the modern military-industrial complex. In his spare time, he dabbled in science fiction and poetry.

After the war, Bogdanov became fascinated with the idea of blood transfusions, particularly as a method of extending one’s life. According to Gizmodo, he even believed that he could make himself immortal through these transfusions.

Throughout the 1920s, he subjected himself to a series of blood transfusions, which he claimed had several positive effects on him. He said that his eyesight had improved and his hair had stopped falling out. His friends even told him that he looked younger.

Unfortunately, Bogdanov’s hubris got the better of him. For someone so obsessed with blood, he had little foresight — or capability — to actually test the substance before the transfusions.

In 1928, Bogdanov took the blood of a student who had both malaria and tuberculosis. The student made a full recovery after being injected with some of Bogdanov’s blood. Bogdanov, on the other hand, became incredibly ill and died shortly after.

Robert Nelson, The TV Repairman Who Was Obsessed With Cryonics

Bob Nelson (left) and biophysicist Dr. Dante Brunol cryonically freezing a patient in 1967.

Robert Nelson was a television repairman and a high school dropout with no scientific background. What he did have, however, was a deep obsession with cryonics, the idea that humans could be posthumously frozen and then revived in the distant future after scientists found a cure for aging.

Nelson told Los Angeles Magazine in 2014 that his obsession began after reading Dr. Robert Ettinger’s 1962 book, The Prospect of Immortality, in which Ettinger theorized that death was not an inevitable part of life but rather a disease that could one day be cured. He also theorized that a man could be frozen in the present and thawed out in the future when the technology required to achieve immortality had been discovered.

Nelson was infatuated with the idea, and he even met Ettinger before the author died — and was subsequently cryonically frozen.

Despite lacking the credentials, Nelson attended the first meeting of the Suspended Animation Group, which was dedicated to the idea of cryonic freezing. His passion must have preceded him, because he was voted president. With Nelson at the helm, the group then formed the Cryonics Society of California, a non-profit largely made up of believers who dreamed of being cryonically frozen.

Unfortunately, it was also largely made up of non-scientists. Still, in 1967, they found a volunteer willing to undergo cryonic preservation: 73-year-old psychology professor Dr. James Bedford. Bedford was dying of kidney cancer and had agreed to let the Cryonics Society freeze his body.

Bedford passed away on Jan. 12, 1967. After days of quite literally being put on ice, his cryonic coffin was completed. Nelson and a few “pothead friends” he had enlisted for help loaded the dead man in, injected what was essentially antifreeze into his veins, and surrounded him with dry ice.

Over the next decade, Nelson’s organization continued to grow, though it always struggled with funding and suffered from a lack of expertise. He ultimately walked away from the venture in 1979.

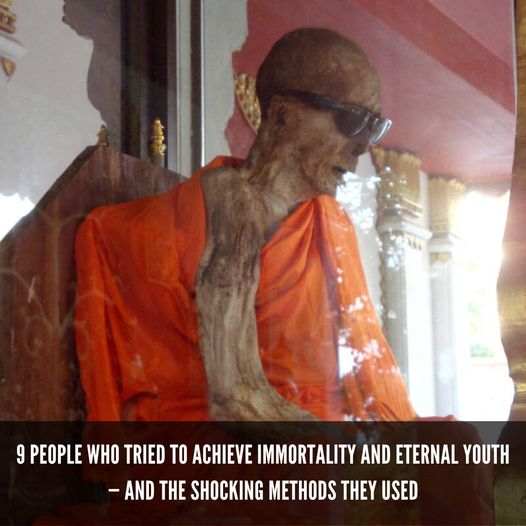

Sokushinbutsu, The Buddhist Self-Mummifying Monks

The body of a monk who underwent self-mummification.

Between 1081 and 1903, around 30 living Shingon monks underwent the process of sokushinbutsu — or self-mummification.

In order to complete this macabre process, the Japanese monks adopted a diet known as mokujiki, or “tree-eating,” by foraging in nearby forests and subsisting exclusively on tree roots, bark, pine needles, nuts, and berries. The purpose of the extreme diet was to prepare the body for biological mummification by removing any fat and muscle from the frame. It also helped the body avoid decomposition by depriving it of its naturally-occurring bacteria formed from vital nutrients and moisture.

This spiritually-imposed diet could last up to 1,000 days. Then, according to the Penn Museum, the monk would move on to the next phase: sanrō, or “confinement” on the mountain. This could go on for 4,000 days.

Finally, the monk was placed into a pine coffin and buried ten feet underground with nothing more than a bamboo rod to breathe through. He would ring a bell periodically to let his followers know that he was still alive, but otherwise, the monk did nothing but meditate until he died of starvation.

When the bell stopped ringing, the monk’s followers would remove the bamboo rod and seal the tomb for 1,000 days. After those three years and three months had passed, they would remove the monk from the ground and examine him. If his body showed signs of decay, they would simply reinter him. If not, he was considered a true sokushinbutsu, dressed in bright robes, and enshrined.

The mummified bodies of 21 sokushinbutsu survive in Japan to this day. In a way, they indeed succeeded in achieving immortality.