Many ancient festivals had elements that were far from innocent, often involving rituals, practices, and customs that might seem strange or even disturbing by today’s standards. From bloodletting, to stoning outcasts, all the way to sacrificing many animals, these festivals were anything but festive. But even so, they had special meaning for the ancient people who practiced them. Here are 10 ancient festivals that were far from innocent.

1. Lupercalia (Roman Empire)

Lupercalia was an ancient Roman festival celebrated annually on February 13th-15th. This peculiar festival was dedicated to the Roman god Lupercus (often associated with Faunus) and celebrated fertility and purification. The festival had a unique blend of rituals, some of which might seem bizarre by contemporary standards.

One of the central activities of Lupercalia involved the sacrifice of goats and dogs. After the sacrificial offerings, young men known as “Luperci” would strip naked and use strips of goatskin to whip women and crop fields. This act was believed to promote fertility and protect against evil spirits. It’s important to note that women willingly participated in this tradition, as they believed it could enhance their chances of conceiving.

The Lupercalia Festival in Rome: Cupid and Personifications of Fertility encounter the Luperci. (Public Domain)

Lupercalia’s association with fertility and purification was further evident in the custom of matchmaking. During the festival, young men and women would draw lots to form temporary couples, sometimes leading to marriages. This practice was a precursor to the modern concept of “blind dates.” Despite its apparent strangeness, Lupercalia was a significant event in ancient Rome, steeped in tradition and belief. Over time, some elements of the festival evolved and intertwined with the early Christian holiday of Valentine’s Day, which now celebrates love and affection in a considerably tamer fashion.

2. Thargelia (Ancient Greece)

Thargelia was an ancient Greek festival with deep religious significance, primarily dedicated to Apollo and Artemis. It was celebrated annually in various Greek city-states, with Athens being one of the most prominent locations for this festival. Thargelia typically took place in the month of Thargelion, roughly corresponding to May in the modern calendar.

The festival’s rituals had both positive and negative aspects. On one hand, it was a time for celebrating the harvest, offering first fruits to the gods, and expressing gratitude for their blessings. People would engage in feasting, singing, and dancing as a way of honoring the divine.

On the other hand, Thargelia also featured a dark and somewhat unsettling tradition. A purification ceremony called “pharmakos” involved selecting two individuals, typically marginalized or undesirable members of society, who would symbolically absorb the community’s sins and troubles. These individuals, often foreigners or beggars, were dressed in rags, paraded through the city, and then either expelled or, in some cases, sacrificed to cleanse the community.

During the ancient festival of Thargelia, the pharmakos was a person, often a societal outcast or someone considered impure, who was expelled from the community as a means of purifying it from perceived evils or misfortunes. (Public Domain)

The purpose of the pharmakos ritual was to purify the city and protect it from misfortune. It reflected the ancient Greek belief that by eliminating these scapegoats, the community could rid itself of negative influences and ensure its continued well-being. Thargelia served as a reminder of the complex and multifaceted nature of ancient Greek religious practices.

3. Saturnalia (Roman Empire)

Saturnalia was one of the most popular and festive celebrations in ancient Rome, taking place over several days each December, usually between December 17th and 23rd. The festival was dedicated to Saturn, the god of agriculture, and marked the winter solstice, a time of transition and renewal. Saturnalia was characterized by a temporary suspension of social norms and hierarchy, allowing for a topsy-turvy atmosphere that contrasted with everyday Roman life.

During Saturnalia, various customs and practices were observed. People exchanged gifts, particularly small figurines and candles, and it was customary to give small presents, known as “strenae,” to children. Social roles were reversed, with slaves being served by their masters and often participating in feasts as equals. Gambling, singing, and dancing were common, and many people indulged in excessive food and drink.

Painting entitled ‘Saturnalia’ (1783) by Antoine Callet. (Public Domain)

One of the most iconic features of Saturnalia was the use of evergreen boughs and decorations to symbolize the renewal of life and the return of light as the days began to lengthen after the winter solstice. While Saturnalia was a time of merriment and relaxation, it also carried a deeper cultural significance. It allowed Romans to temporarily escape the rigidity of their social structure and provided a sense of unity and equality, even if only for a short period. It served as a much-needed release from the stresses of daily life and a way to celebrate the changing of the seasons and the hope of better times to come.

4. Beltane (Celtic Europe)

Beltane is an ancient Celtic festival celebrated on May 1st, marking the beginning of summer. It is a cross-quarter day, falling roughly halfway between the spring equinox and the summer solstice, and is one of the four major Celtic festivals, alongside Samhain, Imbolc, and Lughnasadh. Beltane, with its focus on fertility, fire, and the turning of the seasons, was a time of great significance in Celtic culture.

One of the central rituals of Beltane involved lighting large bonfires, symbolizing the sun’s growing strength as summer approached. People would leap over these fires, a gesture believed to bring good fortune and protection from harmful influences. The smoke and ashes from the bonfires were considered purifying and were used to bless livestock and fields.

Beltane. (chrisdonia/CC BY NC SA 2.0)

Couples would often join in hand fasting ceremonies, a precursor to modern hand fasting or marriage rituals, where they pledged their commitment to each other for a year and a day. This practice symbolized the union of the god and goddess, celebrated during Beltane.

Beltane was also a time for dancing, music, and feasting, as the community celebrated the lush fertility of the land and the promise of a bountiful summer harvest. The Maypole, adorned with colorful ribbons, was a central feature of the celebrations, and people would dance around it, weaving intricate patterns with the ribbons. However, not all was completely innocent – in some parts of the pagan world, the Beltane was accompanied by orgies where intercourse was done in plain view, in celebration of fertility gods.

Today, Beltane is still celebrated by modern pagans and Wiccans as a time to honor the Earth’s fertility and the interconnectedness of all living things, often with outdoor rituals, dances, and feasts that pay homage to the festival’s ancient roots.

5. Carthaginian Child Sacrifice (Carthage)

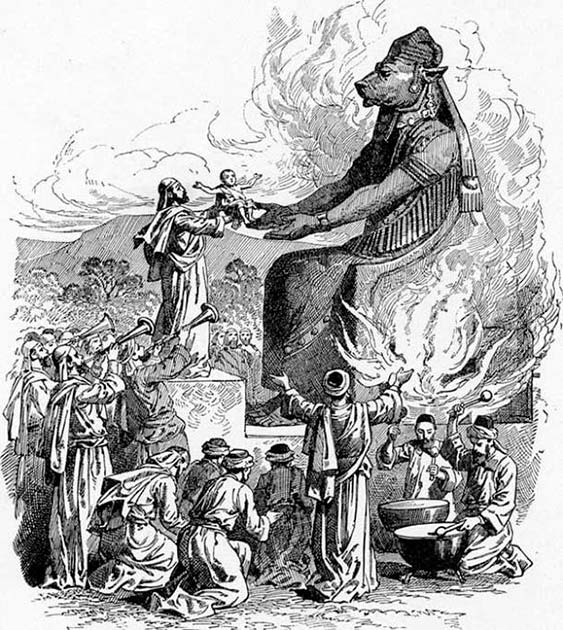

Carthaginian child sacrifice, often associated with the worship of the god Baal Hammon, was a controversial and horrifying practice in the ancient city of Carthage, located in what is now modern Tunisia. The historical accounts of child sacrifice in Carthage come from various sources, including Greek and Roman writers, as well as archaeological evidence.

The practice typically involved the ritual sacrifice of infants, sometimes toddlers, and even older children. While the exact details varied, many accounts describe placing the child on the outstretched arms of a bronze or iron statue of Baal, heating the statue until it glowed, and then allowing the child to fall into a pit of fire below. Some sources also mention the use of drums and music to drown out the cries of the victims.

Ritual sacrifice of children to Moloch from ‘the Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us’ by Charles Foster (1897) (Public Domain)

The reasons for this gruesome practice are still debated by scholars. It is believed that Carthaginians saw child sacrifice as a means of appeasing their gods, seeking protection, and ensuring prosperity, especially in times of crisis. Some suggest that it may have been linked to concerns about dwindling resources or political turmoil. Child sacrifice in Carthage has left a dark mark on history, as it is one of the most disturbing aspects of ancient religious practices. It is a poignant example of how cultural and religious beliefs, at times, led to horrific and morally abhorrent actions.

6. Perchtenlauf (Austria and Germany)

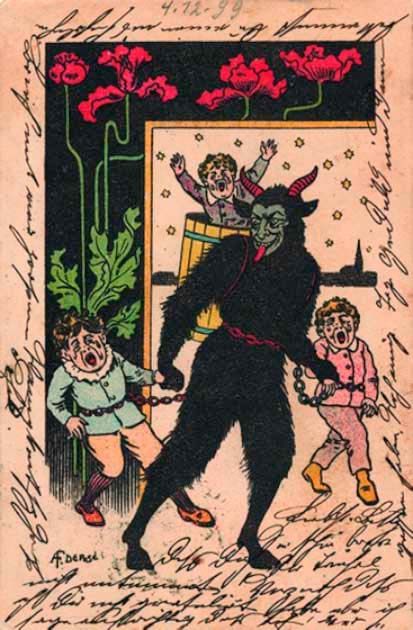

Perchtenlauf, also known as the Krampus Run, is an intriguing and somewhat eerie Alpine festival that takes place in Austria, Germany, and other parts of the Alpine region. This event typically occurs during the winter, often in the lead-up to Christmas, and involves participants dressing up in elaborate, frightening costumes reminiscent of mythical, horned creatures known as “Perchten.”

The Perchten are believed to be spirits that either punish or reward humans. Good Perchten represent benevolent spirits that bring blessings and ward off evil, while the more sinister ones, called “Krampus,” embody malevolent forces and serve as a warning to misbehaving children during the holiday season.

The Krampus of German-speaking folklore is a horned Christmas Devil who punishes misbehaving children. (Public domain)

During the Perchtenlauf, individuals don these elaborate and often terrifying costumes, complete with masks, horns, and fur. They then parade through towns and villages, chasing and playfully scaring onlookers. The festival combines elements of folklore, pagan traditions, and Christian customs, creating a unique cultural spectacle that both entertains and educates, reminding people to stay on the right path and maintain good behavior during the holiday season. While Perchtenlauf can be unsettling to witness, it’s a tradition deeply rooted in local culture and a vivid example of how ancient beliefs and customs continue to thrive and evolve in modern times. It’s a testament to the enduring power of folklore and the rich tapestry of European traditions.

7. Vestalia (Ancient Rome)

The Vestalia was an important ancient Roman festival dedicated to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, home, and family. It was celebrated annually from June 7th to June 15th, making it one of the longest-running festivals in the Roman calendar. The festival held a special place in the hearts of Roman citizens, as the hearth was seen as the heart and center of the home, symbolizing the continuity and security of the family.

During the Vestalia, the Vestal Virgins, who were priestesses dedicated to Vesta, played a central role. They conducted various rituals to honor the goddess, including the cleansing and purification of Vesta’s sacred hearth in her temple, the Temple of Vesta. This temple, located in the Roman Forum, was considered one of the holiest places in Rome.

One of the most well-known aspects of the Vestalia was the Penus Vestae, a sacred room within the temple that held the eternal flame of Vesta. Only the Vestal Virgins were allowed access to this room. The continuity of the sacred flame symbolized the ongoing protection and prosperity of the Roman state, making the Vestal Virgins’ role in preserving it of paramount importance. The Vestalia was marked by its modest and solemn character, with the focus on Vesta’s sacred duties. It was also an occasion for Romans to pay special homage to the Vestal Virgins and show their respect for the goddess who safeguarded their homes and the city itself.

8. Festival of Pomona (Roman Empire)

Pomona was the Roman goddess of fruit trees, gardens, and orchards. The festival dedicated to her, known as the Pomonia, was held on November 1st and was a time for offering thanks for the fruits of the earth and for the abundance of the harvest. Some scholars believe that the festival of Pomona and the Celtic festival of Samhain may have influenced the modern holiday of Halloween, which is celebrated on October 31st. However, the extent of this influence is a topic of debate among experts.

Vertumne et Pomone – Peter Paul Rubens, 1617-1619. (Public Domain)

During this festival, which could have been a part of a wider period of festivity dedicated to her consort, Vertumnalia, worshippers would ritually plant a tree which was formed into the shape of a man. It was a symbolic entrance into Autumn, a time when vegetation dies out in preparation of winter. It is quite likely that the festivities had a gruesome aspect as well, when animals were sacrifice to the gods.

9. Thesmophoria (Ancient Greece)

Thesmophoria was an ancient Greek religious festival primarily celebrated by women, dedicated to the goddesses Demeter and her daughter Persephone. The festival was held annually, typically in the month of Pyanepsion (around October), and it was an important event in the Athenian calendar.

One of the central themes of Thesmophoria was the celebration of the fertility of the earth and the mysteries of life and death. It was a three-day event, with the first day involving a procession to Eleusis, the site of the famous Eleusinian Mysteries, which were closely connected to Thesmophoria. During the second day, women would fast and engage in rituals, including the throwing of piglets, symbolic of the underworld, into underground chambers. The rotten remains of these sacrificed animals were later retrieved and mixed with the seeds to promote fertility in the coming year.

Thesmophoria was also a time for discussions of women’s issues, sexuality, and female rites of passage. Women would share their experiences, learn from one another, and build a sense of community during the festival. This ancient Greek festival allowed women a unique space for bonding, reflection, and the exploration of their roles in the cycles of life and death. It exemplified the significance of female-centric religious practices in ancient Greece.

10. Mayan Bloodletting Rituals (Maya Civilization)

Mayan bloodletting rituals were a distinctive and crucial aspect of Mayan religious and cultural practices, particularly during the Classic Period (250-900 AD) of the Maya civilization. These rituals involved the deliberate extraction of blood from the body, typically performed by elites, priests, or rulers, as a form of sacred offering and devotion to the gods.

Maya site of Yaxchilan, Mexico, Late Classic period, depicting king Bird-Jaguar IV and one of his wives, Lady B’alam mut, during a bloodletting rite. (British Museum/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bloodletting was carried out using various methods, such as the use of stingray spines or obsidian blades to make cuts on the tongue, earlobes, genitals, or other body parts. The blood was then collected on bark paper, which was subsequently burned as an offering to the gods.

The Mayans believed that bloodletting established a connection between the physical and spiritual realms. By offering their own blood, they sought to nourish the gods and secure their favor in return for vital resources like rain and agricultural fertility, as well as for prophetic insights into the future. Elaborate bloodletting ceremonies were often part of larger rituals, such as consecrating temples, marking calendar events, or seeking divine guidance. These rituals were documented in hieroglyphic inscriptions, giving us valuable insights into the Mayan worldview, religion, and social hierarchies .