Life gave a bunch of scientists in Alaska a frozen 50,000-year-old bison, and they decided to make dinner out of it.

On a night in 1984, a handful of select guests gathered at the Alaska home of paleontologist Dale Guthrie to eat a stew made from a once-in-a-lifetime delicacy: the neck meat of an ancient bison nicknamed Blue Babe they had recently discovered.

Given the chance, enjoying some well-aged meat is a privilege not all of us will have the chance to try. Of course, it’s not for everyone, but like aged cheese, meat can also offer some flavor nuances not found when served fresh. But this piece of meat was somewhat different.

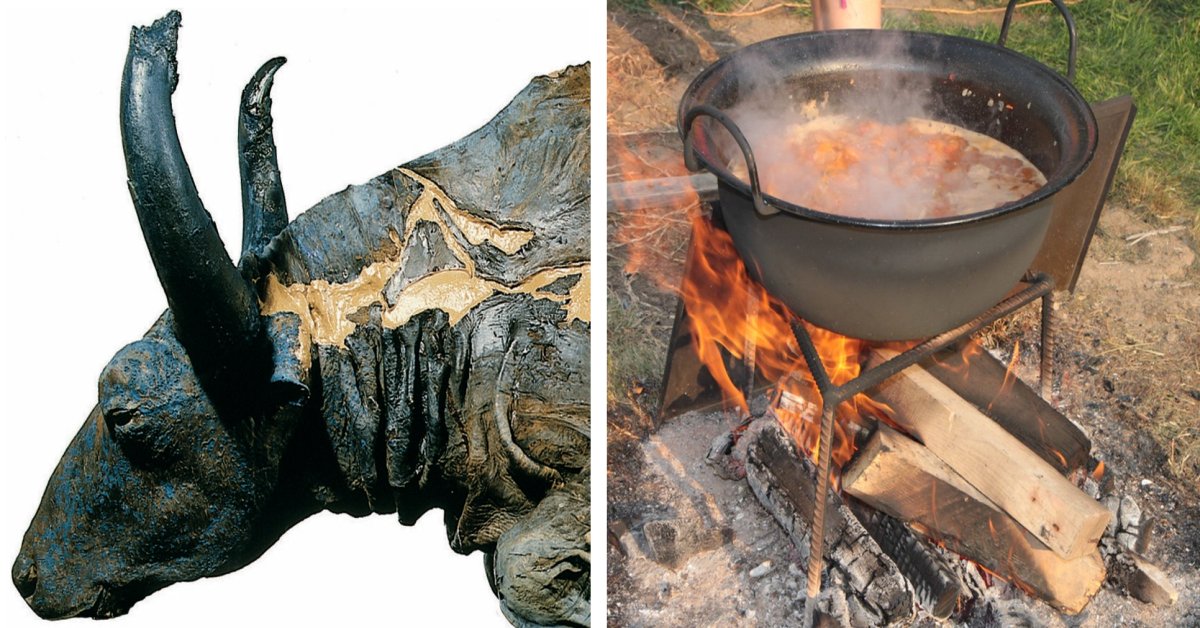

Blue Babe is the mummy of a male steppe bison that was discovered north of Fairbanks, Alaska, five years ahead of the memorable dinner party. The mummy was discovered by a gold miner when a hydraulic mining hose melted part of the gunk that had kept the bison frozen.

The worker named it Blue Babe – “Babe” for Paul Bunyan’s mythical giant ox that permanently turned blue when he was buried to the horns in a blizzard (Blue Babe’s own bluish cast was caused by a coating of vivianite, a blue mineral covering much of its body).

The miners reported the finding to the nearby University of Alaska Fairbanks, where Guthrie – then a professor and researcher at the university – opted to dig out Blue Babe immediately as he was concerned that it would soon decompose. But since the icy, impenetrable surroundings made that feat quite impossible at that point, he decided to cut off what he could, refreeze it, and wait for the head and neck to thaw.

Soon, Guthrie and his fellow researchers had Blue Babe on campus and started finding out more about the ancient animal. Based on radiocarbon dating, they initially thought the animal had perished about 36,000 years ago, but new research shows it is at least 50,000 years old, according to the university’s Curator of Archaeology, Josh Reuther. The tooth marks and claw marks found on the bison suggest that it was killed by an ancestor of the lion, the Panthera leoatrox.

Blue Babe froze rapidly following its death – perhaps due to the fact that it died during wintertime. Indeed, the scientists at the university were amazed to find that the animal had frozen so well that its muscle tissue retained a texture similar to beef jerky. What is more, its fatty skin and bone marrow remained intact too, even after thousands of years. So the researchers thought: why not try eating part of it?

“All of us working on this thing had heard the tales of the Russians [who] excavated things like bison and mammoth in the Far North [that] were frozen enough to eat,” Guthrie said. “So we decided, ‘You know what we can do? Make a meal using this bison.’”

So when taxidermist Eirik Granqvist completed his work on Blue Babe, Guthrie decided to host a very special dinner reception.

“Making neck steak didn’t sound like a very good idea,” Guthrie recalls. “But you know, what we could do is put a lot of vegetables and spices, and it wouldn’t be too bad.”

So Guthrie then cut off a small part of the bison’s neck, where the meat had frozen while fresh. That would probably make a good(?) stew for roughly eight people, wouldn’t it?

“When it thawed, it gave off an unmistakable beef aroma, not unpleasantly mixed with a faint smell of the earth in which it was found, with a touch of mushroom,” Guthrie once wrote. Then the aged meat was punched up by adding a generous amount of garlic and onions, along with carrots and potatoes. Couple that with some red wine, and poor Blue Babe became a full-fledged dinner.

Guthrie, who is also a hunter, says he wasn’t put off by the many millennia the bison had aged, nor the prospect of getting sick from the exceptionally aged meal.

“That would take a very special kind of microorganism [to make me sick],” he says. “And I eat frozen meat all the time, of animals that I kill or my neighbors kill. And they do get kind of old after three years in the freezer.”

Thankfully, everyone present survived to tell the tale – and the remaining part of Blue Babe remains on display at the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

OK, but how did the 50,000-year-old bison stew taste, after all? Not that bad, according to Guthrie. “It tasted a little bit like what I would have expected, with a little bit of wring of mud,” he says. “But it wasn’t that bad. Not so bad that we couldn’t each have a bowl.”

He can’t remember whether anyone present at the unusual dinner party had seconds, though.

Sources: 1, 2, 3