At the height of the Cold War, the USA and the Soviet Union both provided their citizens with guidelines on what to do in case of nuclear war. Here’s how the Soviets did it.

When in August 1945 the USA unleashed a new weapon of mass destruction against the Japanese at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it brought an end to World War II. Unlike conventional bombs, the new atomic bomb killed in two ways – by the sheer magnitude of the blast and the resulting firestorm, and by means of nuclear fallout.

In 1945, the USA still had a monopoly on this new dreadful weapon, but not for long. Four years later, the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb. Although the USA and the USSR had been wartime allies, by this time they had become peacetime enemies with conflicting ideologies and competing global interests. Maintaining an advantage in the power and numbers of nuclear weapons suddenly meant world power, so both nations embarked on a long and insane arms race while also preparing their citizens for a potential nuclear attack.

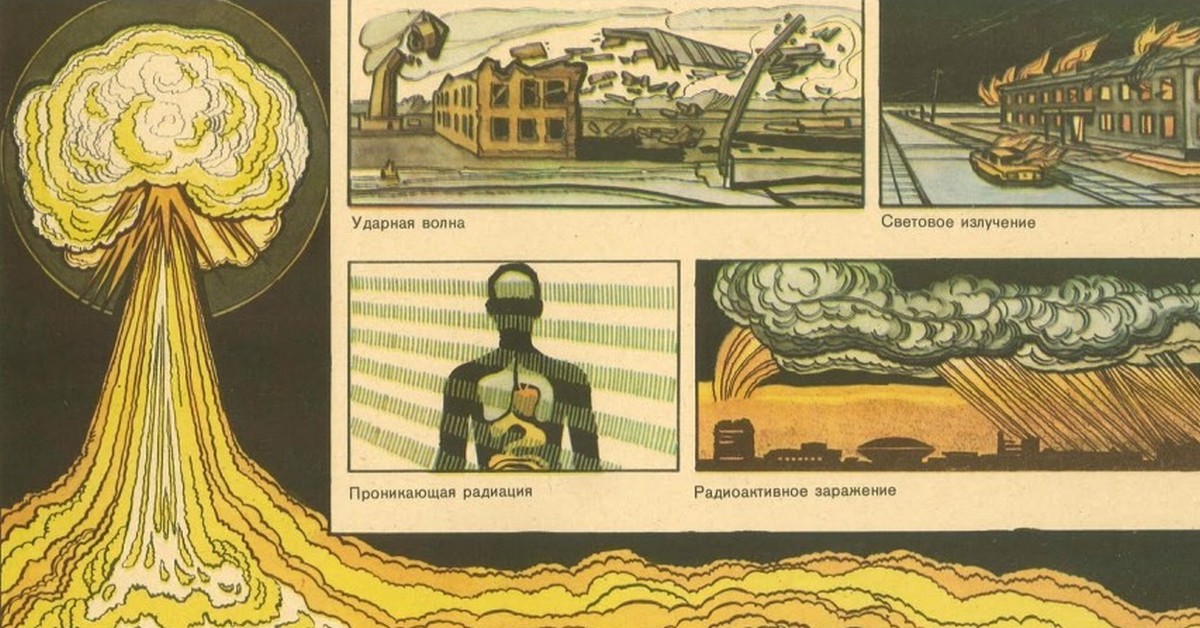

These images from a pamphlet show what the Russian side did to communicate the hazards.

The fear of imminent war was one of the most dominant fears of the Soviet post-war era, according to Belarus news. Soviet citizens were waiting for a new war to come more or less constantly. Take, for example, the so-called Caribbean crisis of 1962, when the USSR installed missiles with nuclear warheads in Cuba to demonstrate its strength to the United States, bringing the world on the verge of a third world war.

Soviet citizens also expected a nuclear war in 1979, when the USSR sent troops into Afghanistan. Another scary moment came in 1983, when Soviet air defenses shot down a South Korean passenger plane, and in a famous speech Ronald Reagan called the USSR an “evil empire.” Soviet propaganda, which during the entire period of the Cold War spoke about the aggressiveness of foreign opponents of the USSR (they were called “warmongers” in the newspapers), reacted to each such crisis by intensifying alarmist rhetoric, which did not at all reassure citizens.

In the course of the Cold War, the worsening of the “international situation”, the tightening of newspaper rhetoric, and the participation of the Soviet Union in local conflicts were acting as triggers for the emergence of new waves of rumors about the war. The Soviet citizen had very few opportunities to influence state politics, with all important political decisions being made by the head of the state and a group of his closest comrades. There was a most direct link between the stability of life and the personality of the head of state. Therefore, the death of a leader could cause serious anxiety, often taking on the form of fear of war.

The death in 1982 of Brezhnev, who had served as general secretary for almost twenty years, caused some Soviet citizens strong anxiety and a sense of the impending apocalypse. Particularly susceptible to this feeling were children who had not yet reached the age when jokes were told about the elderly general secretary. There were rumors that a war would come, that Brezhnev held the “key” of the world in his hand, and now his fist is unclenched and… “. A former Leningrad schoolgirl said that on the day of Brezhnev’s death, her neighbor, a 12-year-old boy, came from school crying and saying, “I was also afraid that there would be a war.”

Although Soviet citizens were taught in civil defense lessons what to do in the event of a nuclear war – soak clothes with a special solution, put on a cotton-gauze bandage, run to a bomb shelter – many understood that all these actions in the event of a nuclear apocalypse would not save anybody.

This knowledge is evidenced, in particular, by dreams. The most “optimistic” version of a dream on the topic of nuclear war would be a plot where the dreamer finds himself in an empty ruined city and realizes that he has entered the space of the post-apocalypse and all living things around him have died. More typical was the version described by Soviet film director Andrei Tarkovsky below, where the dreamer, noticing a nuclear mushroom on the horizon, wakes up in horror from the realization of the inevitability of the end.

Instructions for using the bomb shelter often did not reassure, but, on the contrary, inspired anxiety, especially that sometimes life showed their complete uselessness. Upon a strong explosion at the Sverdlovsk-Sortirovochnaya railway station in the city of Sverdlovsk in 1989, some citizens, waking up early in the morning from a strong jolt and seeing a glow in the sky, decided that a nuclear war had begun and they needed to go to a bomb shelter.

Someone even packed a bag with the things necessary for the bomb shelter, but before leaving the apartment she realized that she did not know where it was and did not understand how to proceed at all. All the actions she had been trained to do proved to be useless.

Some parents and older relatives in general, however, did not share the children’s fear inspired by military instructors, teachers and counselors. The desire of a child to write a letter to Reagan, to find a gas mask for a dog, or to definitely run to a bomb shelter on a training alert caused bewilderment or a smile in the elders.

A reader told Belarus News how she was worried when her parents stayed at home during a training trip to a bomb shelter. Another, fearful of the nuclear threat, wrote a letter to Reagan but did not send it because she was ridiculed by her older brother.

Nevertheless, adults sometimes had terrible dreams about a nuclear explosion too. It was such a dream that director Andrei Tarkovsky wrote about in his diary in 1982:

I fell asleep – and I dreamed of a village and a heavy, gloomy and dangerous dark purple sky. Strangely lit and scary. Suddenly I realized that it was an atomic mushroom against the sky, and not dawn. It was getting hotter and hotter, I looked around: a crowd of people in a panic looked back at the sky and rushed somewhere to the side. I was rushing after everyone, but stopped. “Where to run? Why?” It’s already too late anyway. Then this crowd… Panic… It’s better to stay where you are and die without fuss. God, it was scary!

The expectation of a nuclear war caused not only fear of the enormous destructive power of nuclear weapons, but also a feeling of helplessness, doom and inability to control the situation – and this feeling is very well conveyed in the description of Tarkovsky’s dream.

Of course, this feeling was not specifically Soviet – it was experienced by people on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

These days those feelings are again intensifying again. Back then, soviet citizens could only keep their fingers crossed, but today most of us in the world have more freedom to stand up against any form of war. So let’s do it.

Sources: 1, 2