The Bell X-1 was a rocket-powered aircraft designed by Bell for a supersonic joint research project between the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the US Army Air Forces (USAAF), later the US Air Force. Initially conceived during the Second World War and built in 1945, the X-1 became the first aircraft to exceed the speed of sound in level flight.

Design and development of the Bell X-1

In 1942, the British Ministry of Aviation began working on a secret project with Miles to produce the world’s first aircraft capable of exceeding the speed of sound. The turbojet-powered M.52 could hit 1,000 MPH and reach an altitude of 36,000 feet in only one minute and 30 seconds.

In 1944, the Ministry of Aviation signed an agreement with the United States to share its research and data. Later that same year, engineers from Bell Aircraft visited Miles and were shown drawings and research pertaining to the development of the M.52. By this time, the American company had already begun designing a rocket-powered aircraft.

Bell X-1 specs

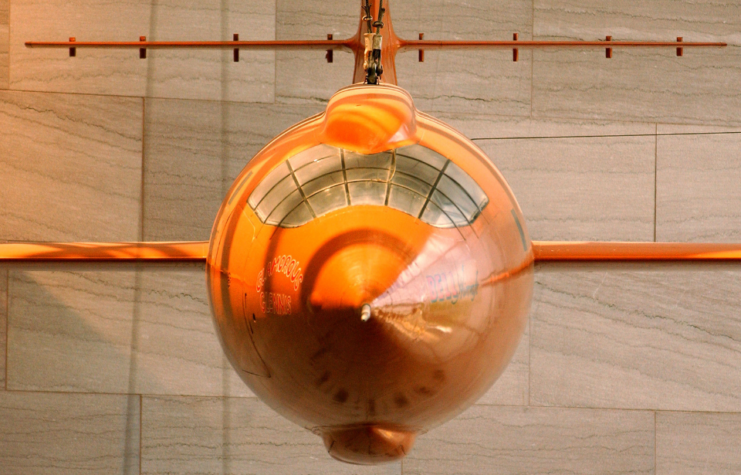

The Bell X-1 had an overall bullet-shaped fuselage with short, stubby wings. The design was optimized for high-speed flight, with low drag and a powerful engine. The aircraft was primarily made of aluminum alloy and fitted with a pressurized cockpit. As its sole purpose was speed, the pilot had a diminished view out of a significantly sloped windshield and didn’t have an ejection seat.

Short straight wings were used, instead of swept ones, due to a lack of knowledge of their efficiency at high speeds. Issues with the aircraft’s compressibility arose in 1947, and it was decided a variable-incidence tailplane would be added. This was similar to the variable-incidence wing seen on the Vought F-8 Crusader.

The X-1 was powered by a single Reaction Motors XLR11-RM-3 four-chamber liquid-fueled rocket engine, producing 6,000 pounds of thrust. Engineers at Bell had considered using turbojet engines, but they couldn’t reach the speed required at high altitudes, and an aircraft that used both turbojet and rocket engines would be far too large and overly complex.

The engine ran on ethyl alcohol diluted with water, with a liquid oxygen oxidizer. The chambers could each be turned on and off individually, allowing the X-1 to change its thrust in 1,500-pound increments. The fuel and oxygen tanks were pressurized with nitrogen, reducing flight time by about one and a half minutes and increasing landing weight by 2,000 pounds.

The X-1 would only take off from a runway once, due to the desire in its design leading to future fleet aircraft with the ability to reach similar high speeds. It was decided that it would be easier to deploy the X-1 via a Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

Putting the aircraft to the test

The Bell X-1 first took to the skies on January 19, 1946. With chief test pilot Jack Woolams at the controls, it completed a glide flight at Pinecastle Army Airfield, Florida. Another test involved the X-1 being dropped from a B-29 Superfortress at 29,000 feet.

Four additional glide tests were conducted at Muroc Army Air Field, California, with the first powered test taking place on December 9, 1946 by Chalmers “Slick” Goodlin. During the flight, only two engine chambers were ignited – however, the X-1 accelerated so fast that one was shut down. At 35,000 feet, it reached a speed of Mach 0.795. The engine was then turned off, and the aircraft descended to 15,000 feet, where all four chambers were tested.

On May 22, 1947, Alvin “Tex” Johnston, Bell’s chief test pilot and program supervisor, completed another test flight. During this, the X-1 reached Mach 0.72, and Johnston concluded that the aircraft was ready to be tested for supersonic flights. Bell wanted to be sure before advancing the program and another three flights were performed.

Breaking the sound barrier

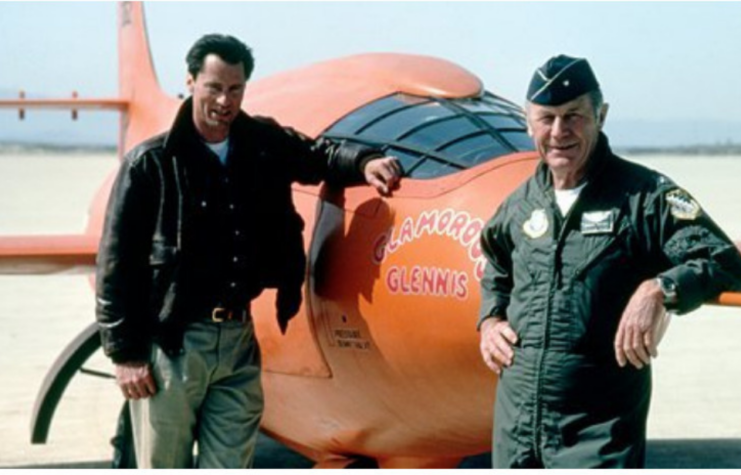

The first supersonic flight of the Bell X-1 took place on October 14, 1947, conducted by Charles “Chuck” Yeager over the Mojave Desert. The aircraft, nicknamed Glamorous Glennis for his wife, was dropped from a B-29 and hit Mach 1.06 (700 MPH). After the engine burned out, the X-1 glided until it landed on the dry lakebed.

The supersonic flight was top secret. That being said, it leaked to Aviation Week and was headline news for the Los Angeles Times in December 1947. The US Air Force threatened legal action against the news agencies and the individual journalists involved, but this never occurred. On June 10, 1948, Air Force Secretary William Stuart Symington III publicly announced that the sound barrier had been broken by an experimental aircraft.

Bell X-1’s legacy

The Bell X-1 set a standard for all X-craft projects that followed, including four variants of the original aircraft. It also created invaluable research that set in motion American fighter design, with effects throughout the latter half of the 20th century.