For many US Air Force pilots, one of the most deadly places to battle the enemy during the Korean War was MiG Alley. The site of the first large-scale jet-versus-jet air fights, with the North American F-86 Sabre, it saw the communist forces make use of Soviet MiG-15s, which, it turns out, were largely piloted by veterans from the USSR.

The USSR shows support for China and North Korea

Prior to the start of the Korean War, Soviet pilots who had fought in World War II were sent to China to train the country’s newly-formed People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF). Both later unofficially committed support and supplies to North Korea once it began its fight against the South in 1950.

When they commenced the war, the North Koreans flew a small number of Soviet aircraft they’d had on retainer since the Second World War. However, their pilots were inexperienced and, once the UN committed air units to the conflict, they quickly became depleted against the US Air Force’s North American P-51 Mustangs.

The majority of the Soviet pilots were given preliminary training at bases in the Soviet Maritime Military District. Eventually, the 64th Fighter Aviation Corps (64th IAK) of the Soviet Air Forces became attached to the PLAAF under the 1st United Air Army.

On the same day the 64th IAK became attached to the 1st United Air Army, the Soviet pilots flying over North Korea engaged in their first dogfights with UN aircraft. They did well against the P-51s, forcing the US-based pilots to switch to the new F-86 Sabre.

Soviet aid was intended to be a secret

While it had long been an open secret that the Soviet Union had provided pilots to fight alongside the Chinese and North Korean forces, it wasn’t until its archives were opened that the long-denied fact was proven to be true.

In an attempt to hide their identities, Soviet pilots were made to wear civilian clothing or North Korean uniforms. Their fighters were covered in Chinese and North Korean markings, and they were ordered to only speak Korean when communicating over the radio. Soviet government officials also frequently denied their pilots were involved in direct combat in Korea.

Despite these precautions, the Soviets were eventually found out. F-86 Sabre pilots reported seeing non-Asian flyers in the cockpits of MiG-15s, and, in March 1951, the 1st Radio Squadron, Mobile (RSM) picked up Russian ground controllers communicating with communist aircraft. Before long, the Soviet pilots were also caught speaking Russian.

The UN forces noticed, as well, that the North Korean and Chinese pilots were much less skilled in their abilities than the Soviets, leading to the latter being nicknamed “Honchos” – Japanese for “Boss.”

What was MiG Alley?

MiG Alley was created out of Soviet Dictator Joseph Stalin‘s fears of having the country’s MiG-15s captured by the UN forces. He was worried about the consequences such an incident would cause and thus ordered his pilots to not fly too far south. As such, they rarely flew south of the Chunchŏn River.

With the southern border of MiG Alley established, it’s time to look at the north. The primary MiG-15 base was located just across the Yalu River in Antung Province, Manchuria. It was surrounded by additional bases that, too, housed the aircraft and their pilots, and together they formed the “Antung Complex.”

The Soviet forces ensured the bases were equipped with the latest defense technologies. These included searchlights, radar installations, anti-aircraft guns and ground control systems. The bases’ locations also allowed officials to rotate MiG-15 units, which, in theory, would allow them to constantly deploy well-rested pilots and reduce casualties.

Having their bases situated on the Chinese side of the border was important to the communist forces, as it was against the rules of engagement for UN pilots to cross the Yalu River and attack. This created a rather tight area for air-to-air combat, making the fighting between pilots particularly dangerous – and difficult.

MiG-15s versus F-86 Sabres

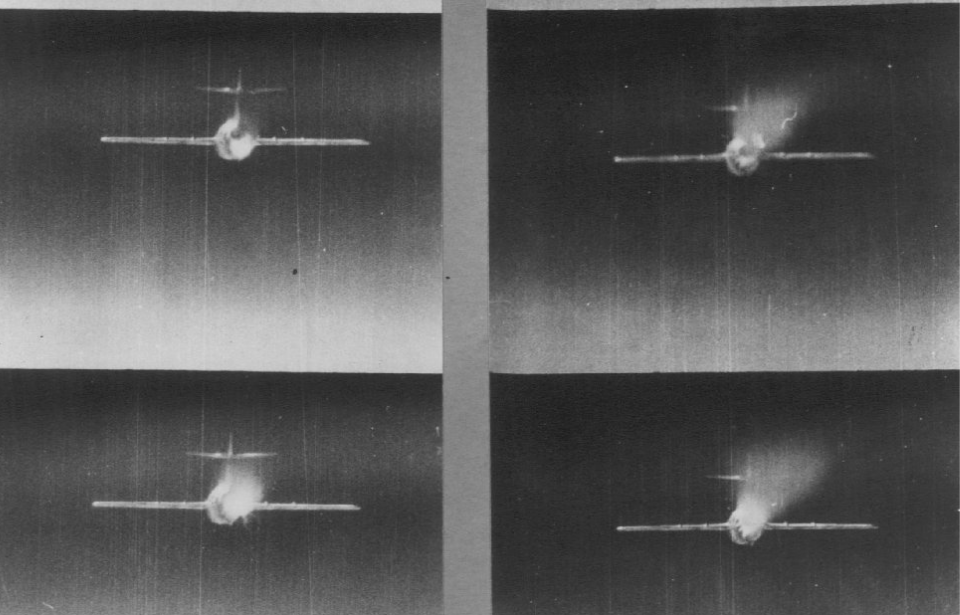

Right off the top, the MiG-15s appeared to be the better aircraft. They carried one 37 mm Nudelman N-37 Cannon and two 23 mm Nudelman-Suranov NS-23 cannons. While able to inflict damage against UN aircraft, the weapons fired at a relatively slow pace. Issues also arose in 1953, when the majority of the MiG-15s were being flown by pilots from China and North Korea, as opposed to the Soviet Union.

The primary bases for the US Air Force’s F-86 Sabres were at Suwon (K-13) and Kimpo (K-18). The F-86 was America’s modern fighter, equipped with six Browning M3 .50-caliber machine guns that, while able to fire at a high rate, could only cause light damage against the communists’ MiG-15s. The aircraft also wasn’t as agile, couldn’t fly as high or rise as fast as the enemy aircraft, but made up for this with its aerodynamics, radar gunsight and the speeds at which it could dive.

Oftentimes, the dogfights occurred once UN aircraft entered the airspace of MiG Alley. On the Manchurian side of the border, MiG-15 pilots laid in wait and, once they spotted the enemy fighters, swooped down from high altitudes to attack. When they ran into trouble, they flew back to China. While the UN forces were technically prevented from crossing the border, many pilots took advantage of the “hot pursuit” exception to do so and adopted a “code of silence” about their patrols.

Despite having an advantage in MiG Alley, the communist pilots couldn’t compete with the better-trained pilots from the US Air Force. While initially the kill ratio was said to be 10:1, in favor of the UN forces, it was later changed to 8:1.

Numerous air aces came out of MiG Alley

The dogfights in MiG Alley produced a number of air aces throughout the Korean War. The top flyers were on the Soviet side, with Nikolai Vasilyevich Sutyagin claiming the most kills at either 21 or 22, depending on the source. Other notable Soviet pilots were Yevgeny Georgievich Pepelyayev with 19 aircraft downed and Lev Kirillovich Shchukin with 17.

On the UN side, the top fighter ace was Capt. Joseph C. McConnell Jr., who downed 16 MiG-15s, including three in one day. He sadly died shortly after returning home in 1954, when the F-86H he was test flying crashed following a control malfunction, which was later attributed to a missing bolt.

The second-highest-scoring ace was also the UN’s first jet-versus-jet ace, Maj. James “Jabby” Jabara. Prior to flying in Korea, he’d flown P-51 Mustangs in Europe during WWII, scoring 1.5 air victories against the Germans. The third highest UN ace of the conflict was Frederick Corbin “Boots” Blesse, who downed nine MiG-15s during his two combat tours in Korea. In total, he completed 35 Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star missions, 67 with the P-51 and 121 missions while flying the F-86.

Over the course of the Korean War, it’s claimed that 30 F-86 pilots were shot down behind enemy lines. Their fates have never been properly established. Those who survived and were later repatriated after the armistice reported being interrogated by Korean, Chinese and Soviet officials, further proving the open secret of the USSR’s involvement in the conflict.