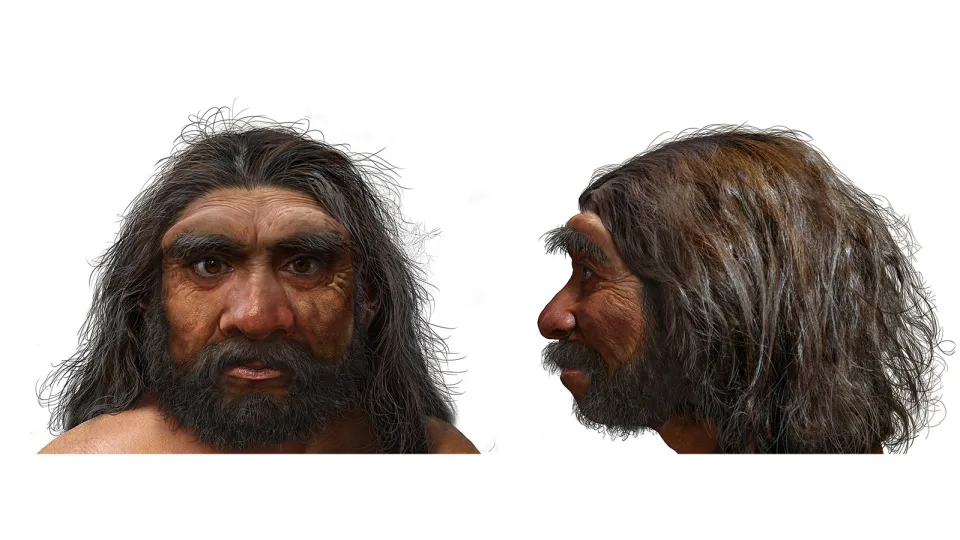

Meet ‘Dragon Man,’ the latest addition to the human family tree

A cranium hidden at the bottom of a well in northeastern China for more than 80 years may belong to a new species of early human that researchers have called “dragon man.”

The exciting discovery is the latest addition to a human family tree that is rapidly growing and shifting, thanks to new fossil finds and analysis of ancient DNA preserved in teeth, bones and cave dirt.

The well-preserved skullcap, found in the Chinese city of Harbin, is between 138,000 and 309,000 years old, according to geochemical analysis, and it combines primitive features, such as a broad nose and low brow and braincase, with those that are more similar to Homo sapiens, including flat and delicate cheekbones.

The ancient hominin – which researchers said was “probably” a 50-year-old man – would have had an “extremely wide” face, deep eyes with large eye sockets, big teeth and a brain similar in size to modern humans.

Three papers detailing the find were published in the journal The Innovation on Friday.

“The Harbin skull is the most important fossil I’ve seen in 50 years. It shows how important East Asia and China is in telling the human story,” said Chris Stringer, research leader in human origins at The Natural History Museum in London and coauthor of the research.

Researchers named the new hominin Homo longi, which is derived from Heilongjiang, or Black Dragon River, the province where the cranium was found. The team plans to see if it’s possible to extract ancient proteins or DNA from the cranium, which included one tooth, and will begin a more detailed study of the skull’s interior, looking at sinuses and both ear and brain shape, using CT scans.

We are family

It’s easy to think of Homo sapiens as unique, but there was a time when we weren’t the only humans on the block. In the millennia since Homo sapiens first emerged in Africa about 300,000 years ago, we have shared the planet with Neanderthals, the enigmatic Denisovans, the “hobbit” Homo floresiensis, Homo luzonensis and Homo naledi, as well as several other ancient hominins. We had sex with some of them and produced babies. Some of these ancestors are well represented in the fossil record, but most of what we know about Denisovans comes from genetic information in our DNA. The story of human evolution is changing all the time in what is a particularly exciting period for paleoanthropology, Stringer said.

The announcement of dragon man’s discovery comes a day after a different group researchers published a paper in the journal Science on fossils found in Israel, which they said also could represent another new type of early human. The jaw bone and skull fragment suggested a group of people lived in the Middle East 120,000 to 420,000 years ago with anatomical features more primitive than early modern humans and Neanderthals.

While the team of researchers stopped short of calling the group a new hominin species based on the fossil fragments they studied, they said the fossils resembled pre-Neanderthal human populations in Europe and challenged the view that Neanderthals originated there.

“This is a complicated story, but what we are learning is that the interactions between different human species in the past were much more convoluted than we had previously appreciated,” Rolf Quam, a professor of anthropology at Binghamton University and a coauthor of the study on the Israeli fossils, said in a news release

Stringer, who was not involved in the Science research, said the fossils were less complete than the Harbin skull, but it was definitely plausible that different types of humans co-existed in the Levant, which was a geographical crossroads between Africa, Asia and Europe that today includes Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Israel, Jordan and other countries in the Middle East.

Concealed treasure

The Harbin cranium was discovered in 1933 by an anonymous Chinese man when a bridge was built over the Songhua River in Harbin, according to one of the studies in The Innovation. At the time, that part of China was under Japanese occupation, and the man who found it took it home and stored it at the bottom of a well for safekeeping.

“Instead of passing the cranium to his Japanese boss, he buried it in an abandoned well, a traditional Chinese method of concealing treasures,” according to the study.

After the war, the man returned to farming during a tumultuous time in Chinese history and never re-excavated his treasure. The skull remained unknown to science for decades, surviving the Japanese invasion, civil war, the Cultural Revolution and, more recently, rampant commercial fossil trading in China, the researchers said.

The third generation of the man’s family only learned about his secret discovery before his death and recovered the fossil from the well in 2018. Qiang Ji, one of the authors of the research, heard about the skull and convinced the family to donate it to the Geoscience Museum of Hebei GEO University.

‘Sister lineage’

The so-called dragon man likely belonged to a lineage that may be our closest relatives, even more closely related to us than Neanderthals, the study found. His large size and where the fossil was found, in one of China’s coldest places, could mean the species had adapted to harsh environments.

“We are human beings. It is always a fascinating question about where we were from and how we evolved,” said coauthor Xijun Ni, a research professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the vice director of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins.

“We found our long-lost sister lineage.”

The study suggested that other puzzling Chinese fossils that paleoanthropologists have found hard to classify – such as those found in Dali in Yunnan in southwestern China and a jawbone from the Tibetan plateau, thought by some to be Denisovan – could belong to the Homo longi species.

Stringer said also it was definitely plausible that dragon man could be a representative of Denisovans, a little-known and enigmatic human population that hasn’t yet been officially classified as a hominin species according to taxonomic rules.

They are named after a Siberian cave where the only definitive Denisovan bone fragments have been found, but genetic evidence from modern human DNA suggests they once lived throughout Asia.

Denisovans is a general name, Stringer said, and they haven’t officially been recognized as a new species – in part because the five Denisovan fossils that exist are so tiny they don’t fulfill the requirements for a “designated type specimen” that would make it a name-bearing representative.

Denisovans and Homo longi both had large, similar molars, the study noted, but, given the small number of fossils available for comparison, it was impossible to say for sure, said Ni, who hoped that DNA experiments might reveal whether they are the same species.

“We’ve only just begun what will be years of studying this fascinating fossil,” Stringer said.