The story of Aníbal Augustus Milhais, also known by the nickname Soldado Milhões (“Soldier Millions”), reads like something out of Star Wars. A simple farmer is called to serve his country during the First World War, and he shows unparalleled bravery, despite the harshest of conditions. After becoming a national hero, he returns to living what many would view as a simple life.

This is Milhais’ story.

Aníbal Augustus Milhais’ upbringing and the start of World War I

Born in 1895, Aníbal Augustus Milhais was a farmer from the Portuguese town of Valongo de Milhais. In 1915, not long after the First World War broke out, he was drafted into the Portuguese military as part of the Infantry of Bragança. He later became a member of the Trás os Montes Brigade of the 2nd Infantry Division of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps.

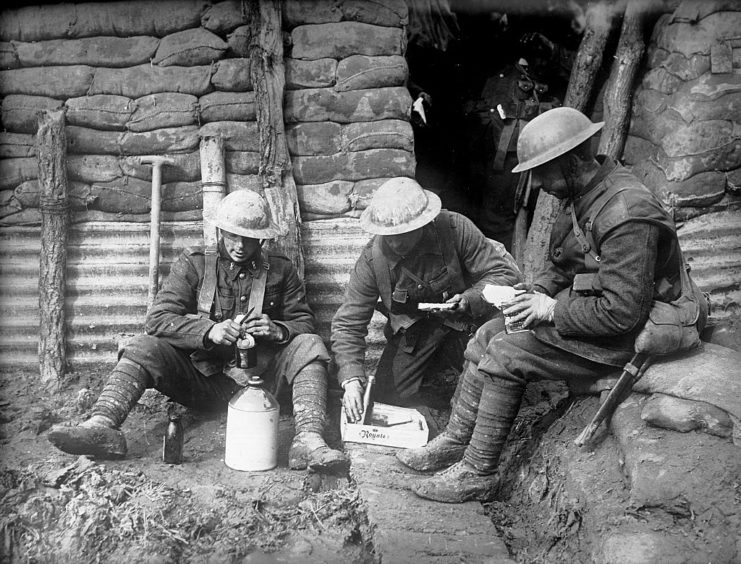

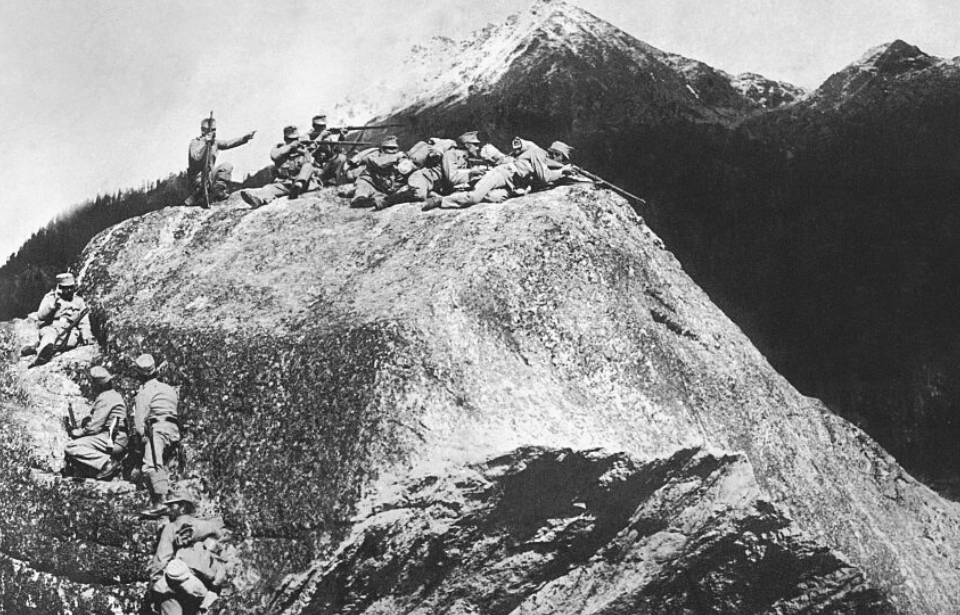

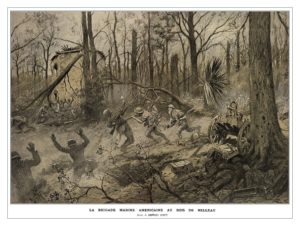

During the First World War, the Portuguese military spent the majority if its time participating in raids in Flanders, Belgium. These raids against German troops were extremely dangerous, with high casualty rates on both sides. Milhais’ group was often assigned to serve on the frontlines during battle, meaning Milhais had the most dangerous job in an already extremely dangerous war. Soldiers serving on the frontlines were often beset with extreme fatigue.

The Battles of the Lys

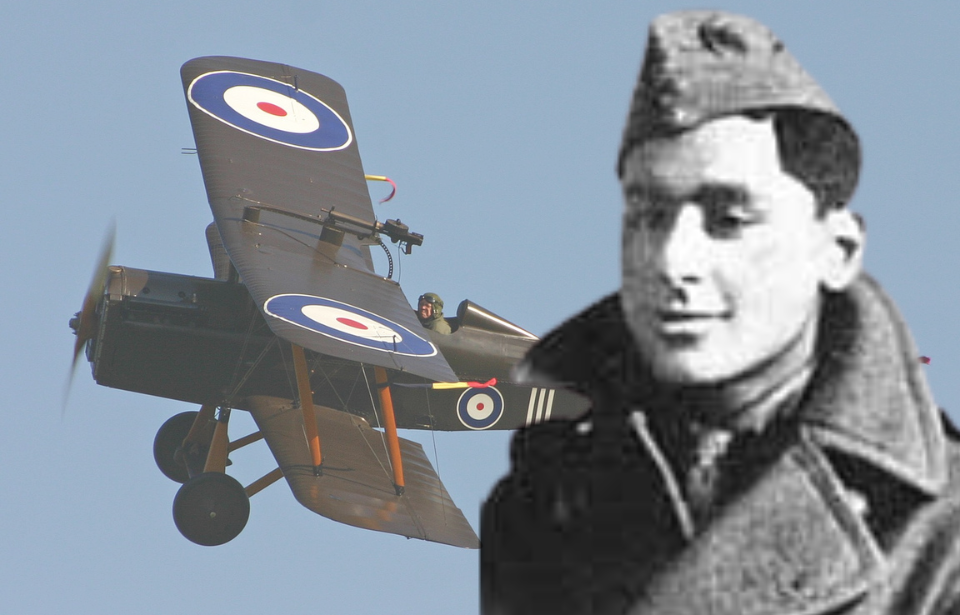

On April 9, 1918, Aníbal Augustus Milhais took part in the Battle of the Lys. During the battle, he was placed in charge of a Lewis gun, a light machine gun capable of firing a large number of rounds. The fighting went poorly, causing the Portuguese and allied Scottish troops to retreat.

Milhais was charged with laying down suppressive fire to protect the retreating troops from the Germans. While under heavy attack, he managed to kill a large amount of enemy soldiers, allowing many of his comrades to escape. Milhais stayed at his post until he ran out of ammunition and found he was all alone. He covered himself under a tarp and evaded capture as the German Army passed him by.

The ordeal was not over yet

Just because Aníbal Augustus Milhais was not captured or killed by the Germans did not mean his ordeal was over. He was all alone, with no idea where his fellow soldiers were. Still armed with his Lewis gun, Milhais made a three-day trek through Flanders. Along the way, he rescued a Scottish major who became his walking companion, and they eventually reached their comrades.

Amazingly, Milhais again proved his valor. Just months after the Battle of the Lys, he single-handedly laid down suppressive fire that allowed a Belgian unit to make it to a secondary trench without any fatalities.

Aníbal Augustus Milhais is rewarded for his actions

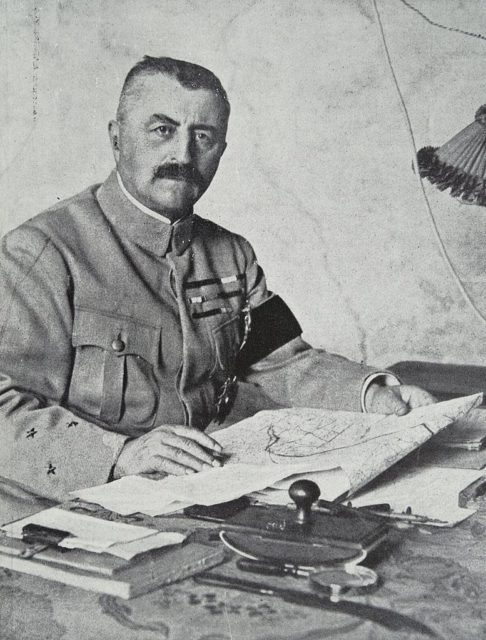

Aníbal Augustus Milhais’ actions were noticed by both British and Belgian officers, who noted his heroism in their reports. He was honored by Portuguese Major Ferreira de Amaral, who memorably stated that he was worth “one million soldiers.” For his service, he was given the Military Order of the Tower and of the Sword, of Valour, Loyalty and Merit, Portugal’s highest honor. He remains the only soldier to have received the medal on the battlefield, as opposed to during a public ceremony in Lisbon.

That wasn’t Milhais’ only award. France gave him the Légion d’Honneur, in front of 15,000 Allied soldiers. When he returned to Portugal, Milhais was seen as a national hero and one of the most famous people in the country.

Aníbal Augustus Milhais’ later life

After his time in the war, Aníbal Augustus Milhais returned to his village and had nine children with his wife, Teresa. Life was hard for the couple, as the Portuguese economy was severely damaged by the war, and they appealed to the government for support. Rather than supporting him monetarily, the government named his hometown, Valongo de Milhais, in his honor.