Is it America’s most capable fighter, or America’s most expensive headache? Why not both?

Refueling under cover of darkness, a massive formation of U.S. Air Force, Royal Air Force, and Australian Air Force aircraft prepared for combat.

Fourth-generation fighters hailing from all three nations—including F-16 Fighting Falcons, F-15 Eagles, and Eurofighter Typhoons—coordinated with E-8 Joint STARS command-and-control aircraft. As their stealthy escorts, both F-22 Raptors and F-35 Joint Strike Fighters surveyed the battle space.

Soon, cockpit displays in each aircraft began to light up and alarms sounded, indicating that the formation was being painted by multiple radar arrays tied to surface-to-air missiles and inbound fighters. Enemy fighters sporting the color schemes of Russian Su-30s began to close in.

“On the last week of a Red Flag exercise we really throw everything we have at the Blue Force and replicate the toughest adversary possible,” says Travolis “Jaws” Simmons, commander of the 57th Adversary Tactics Group.

Ultimately, the F-35 fighter jet won the day, breaking down one of the world’s most advanced air defense networks and relaying the data to missile-packed fighters like the F-16.

The F-35 can fly at speeds as high as Mach 1.6 and can carry an internal payload of four weapons without compromising its stealth. But it’s not the F-35’s firepower that really makes the difference, it’s the computing power. It’s why F-35s have come to be known as “quarterbacks in the sky” or “a computer that happens to fly.”

“There has never been an aircraft that provides as much situational awareness as the F-35,” Major Justin “Hasard” Lee, an Air Force F-35 pilot instructor, tells Popular Mechanics. “In combat, situational awareness is worth its weight in gold.”

But for nearly its entire life, many have debated whether the F-35 is a game-changing platform or a case study in the excesses of the Pentagon’s weapon-acquisition process.

It turns out it’s both.

A 21st-Century Fighter Jet

The Boeing X-32, left, and the X-35 from Lockheed Martin.Joe McNally//Getty Images

The Boeing X-32, left, and the X-35 from Lockheed Martin.Joe McNally//Getty Images

The aircraft we know today as the F-35 was built to meet the demands of multiple fighting forces with a single, highly capable aircraft.

This new “Joint Strike Fighter,” Pentagon officials believed, would allow for streamlined logistical supply lines, maintenance, and training. It would also leverage the same stealth technologies found in the F-22.

With a laundry list of requirements from the U.S. Navy, Air Force, DARPA, and soon, the U.K. and Canada, the Joint Strike Fighter program quickly moved from its official proposal in 1995 to two competitive prototypes in 1997: Lockheed Martin’s X-35 and Boeing’s X-32. And the new fighter had its work cut out for it—the Joint Strike Fighter needed to replace at least five different aircraft across all the different services, including the high-speed interceptor F-14 Tomcat and the tank-killing close air support A-10 Thunderbolt II.

While replacing all these aircraft with one plane would (theoretically) save money, the long list of requirements led to a landslide of expensive complications. In fact, while the X-35 was still competing for the contract, many weren’t sure such an aircraft could even be built in significant numbers.

Lockheed Martin’s F-35: The Specs

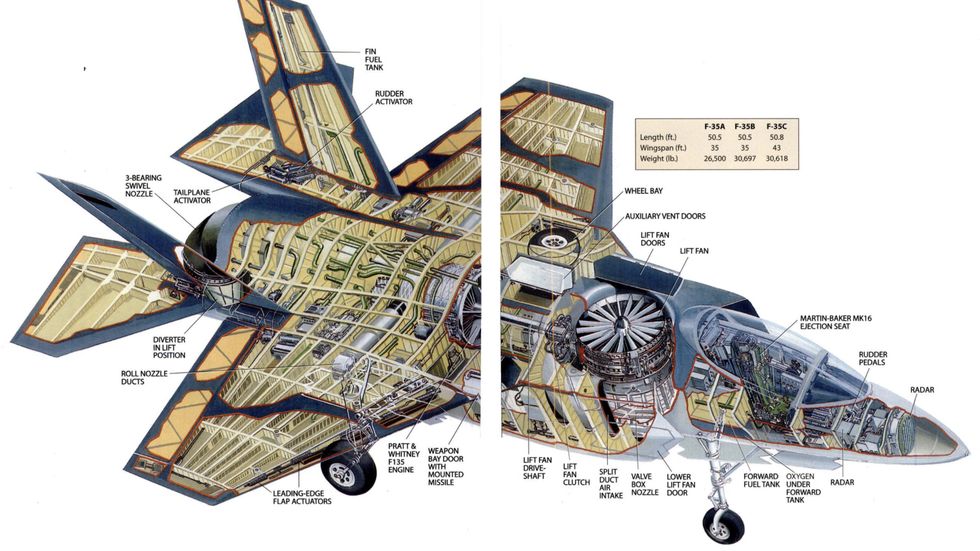

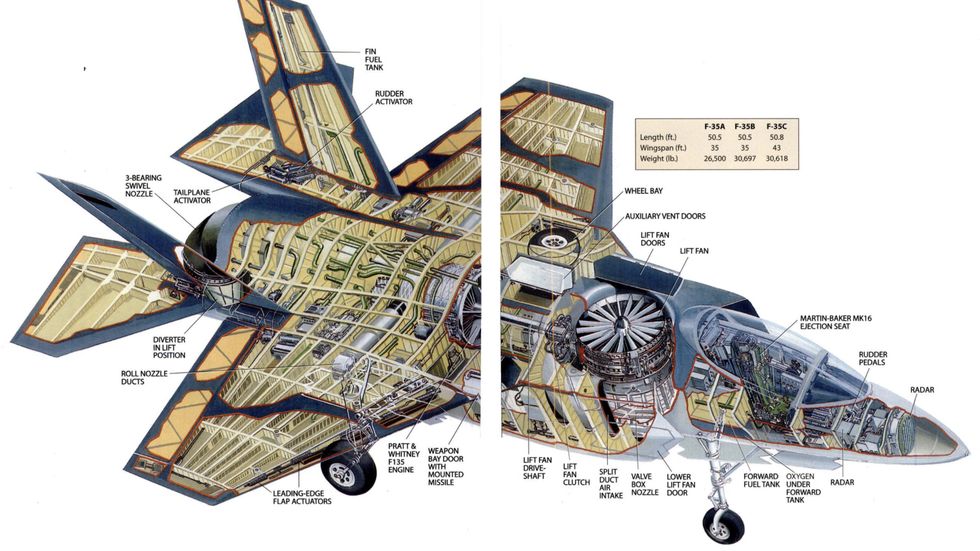

A cross-section of the F-35 from the May 2002 issue of Popular Mechanics. Necessary design changes over the years likely altered these original design plans. Popular Mechanics / John Batchelor

A cross-section of the F-35 from the May 2002 issue of Popular Mechanics. Necessary design changes over the years likely altered these original design plans. Popular Mechanics / John Batchelor

Designed from the ground up to prioritize low-observability, the F-35 may be the stealthiest fighter in operation today. It uses a single F135 engine that produces 40,000 pounds of thrust with the afterburner engaged, capable of pushing the sleek but husky fighter to speeds as high as Mach 1.6. The aircraft can carry four weapons internally while flying in contested airspace, or can be outfitted with six additional weapons mounted on external hardpoints when flying in low-risk environments. The F-35A also comes equipped with an internal 4-barrel 25mm rotary cannon hidden behind a small door to minimize radar returns.

The standard weapons payload of all three F-35 variants includes two AIM-120C/D air-to-air missiles and two 1,000-pound GBU-32 JDAM guided bombs, allowing the F-35 to engage both airborne and ground-based targets. Lockheed Martin has developed a new internal weapons carriage that will eventually allow it to carry an additional two missiles internally.

The cockpit of the F-35 forgoes the litany of gauges and screens found in previous generations of fighter in favor of large touchscreens and a helmet mounted display system that allows the pilot to see real-time information. This helmet also allows the pilot to look directly through the aircraft, thanks to the F-35’s Distributed Aperture System (DAS) and suite of six infrared cameras mounted strategically around the aircraft.

“If you were to go back to the year 2000 and somebody said, ‘I can build an airplane that is stealthy and has vertical takeoff and landing capabilities and can go supersonic,’ most people in the industry would have said that’s impossible,” Tom Burbage, Lockheed’s general manager for the program from 2000 to 2013 told the New York Times. “The technology to bring all of that together into a single platform was beyond the reach of industry at that time.”

While both the X-32 and X-35 prototypes performed well, the deciding factor in the competition may have been the F-35’s complicated Short Take Off and Vertical Landing (STOVL) flight. Because the U.S. Marine Corps intended to use this new plane as a replacement for the AV-8B Harrier Jump Jets, America’s new stealth fighter had to be able to fill the same vertical landing, short take off role.

The Boeing X-32 prototypes were more unusual looking than its X-35 competition and in many ways, were less advanced. Boeing saw this as a selling point because the legacy systems leveraged in its design were cheaper to maintain. The aircraft used a direct-lift thrust vectoring system for vertical landings that was similar to that of the Harrier. It effectively just re-oriented the aircraft’s engine downward to lift the airframe, making it less stable than the X-35 in testing. But Boeing’s biggest mistake may have been the decision to field two prototypes: One that was capable of supersonic flight, and another that was capable of vertical landings. This decision left Pentagon officials worried about Boeing’s ability to field a single aircraft with all of those capabilities crammed inside a single fuselage. USAF//Wikimedia Commons

The Boeing X-32 prototypes were more unusual looking than its X-35 competition and in many ways, were less advanced. Boeing saw this as a selling point because the legacy systems leveraged in its design were cheaper to maintain. The aircraft used a direct-lift thrust vectoring system for vertical landings that was similar to that of the Harrier. It effectively just re-oriented the aircraft’s engine downward to lift the airframe, making it less stable than the X-35 in testing. But Boeing’s biggest mistake may have been the decision to field two prototypes: One that was capable of supersonic flight, and another that was capable of vertical landings. This decision left Pentagon officials worried about Boeing’s ability to field a single aircraft with all of those capabilities crammed inside a single fuselage. USAF//Wikimedia Commons

The lift fan design used in the X-35 connected the engine at the back of the aircraft to a drive shaft that would power a large fan installed in the aircraft’s fuselage behind the pilot. When hovering, the F-35 would orient its engine downward, not unlike the X-32, but it would also pull air from above the aircraft and force it down through the fan and out the bottom, creating two balanced sources of thrust that made the aircraft far more stable.

It also helped the F-35 notch a win in the looks category.

“You can look at the Lockheed Martin airplane and say, that looks like what I would expect a modern, high performance, high capable jet fighter to look like,” Lockheed Martin engineer Rick Rezebek says in a PBS Nova episode. “You look at the Boeing airplane and the general reaction is, ‘I don’t get it.’”

Ultimately, Lockheed Martin won out over Boeing’s unusual looking X-32 prototype in October of 2001. The future looked bright for the newly named F-35.

Complications and Headaches

The F-35 receives a robotic spray of radar-baffling coating along the leading edge of its wing and air intake.Popular Mechanics / Randy A. Crites

The F-35 receives a robotic spray of radar-baffling coating along the leading edge of its wing and air intake.Popular Mechanics / Randy A. Crites

While Lockheed’s lift fan approach to STOVL flight might’ve nabbed the contract, the hard part was just beginning.

Choosing to begin with the least complex iteration of the new fighter, Lockheed’s Skunk Works started designing the F-35A, intended for use in the U.S. Air Force as a traditional runway fighter like the F-16 Fighting Falcon. Once the F-35A was complete, the engineering team would then move on to the more complex STOVL F-35B for use by the U.S. Marine Corps, and then, finally, the F-35C meant for carrier duty.

There was just one problem—jamming all the necessary hardware for the different variants into a single fuselage proved extremely difficult. By the time Lockheed Martin wrapped up design work on the F-35A and got to work on the B, they realized the weight estimates they had established while designing the Air Force variant would lead to an aircraft that was 3,000 pounds too heavy. This miscalculation created a significant setback—the first of many.

Meet the F-35 Variants

To the outside observer, the differences between each F-35 variant can be difficult to detect— and for good reason. The only real differences among each iteration of the jet are related to basing requirements. In other words, the most noticeable differences are in how the fighter takes off and lands.

F-35A

F-35A

Intended for use by the U.S. Air Force and many allied nations, the F-35A is the conventional take off and landing (CTOL) variant. This aircraft is intended to operate out of traditional airstrips and is the only version of the F-35 to come equipped with a 25mm internal cannon, allowing it to step in for both the F-16 multirole fighter and the flying cannon A-10 Thunderbolt II, among many others.

F-35B

F-35B

The F-35B was purpose-built for short take off and vertical landing operations (STOVL) and was designed with the needs of the U.S. Marine Corps in mind. While still able to operate off of traditional runways, the STOVL capability offered by the F-35B allows Marines to operate these jets from austere runways or off the decks of amphibious assault ships, often referred to as “Lightning Carriers.”

F-35C

F-35C

The F-35C is the first stealth fighter ever designed for carrier operations with the U.S. Navy. It boasts larger wings than its peers, to allow for slower approach speeds when landing on a carrier. More robust landing gear aids in tough carrier landings, and it harbors a larger fuel supply (20,000 pounds’ worth) internally to support longer range missions. The C is also the only F-35 equipped with folding wings, allowing for easier storage in the hull of ships.

“It turns out when you combine the requirements of the three services, what you end up with is the F-35, which is an aircraft that is in many ways suboptimal for what each of the services really want,” Todd Harrison, an aerospace expert with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the New York Times in 2019.

Lockheed Martin’s team would eventually work out the finer points of each different platform, leaving as much of the aircraft consistent across branches as possible. But pulling off this engineering magic trick led to a series of delays and cost overruns.

Lockheed Martin’s bad arithmetic in the weight category stretched early development by 18 months and cost a daunting $6.2 billion to correct, but it was just the first of many issues to plague the new Joint Strike Fighter. It wouldn’t be until February of 2006, five years after Lockheed won the contract, that the first F-35A would roll off the assembly line. But these early F-35s weren’t even ready to fight because the Pentagon had chosen to begin production before they had completed testing.

Lockheed Martin chose Pratt & Whitney to power their new stealth fighter, using an F135 engine derived from the F119 used in the F-22 Raptor. The powerful engine produces 40,000 pounds of thrust, just less than the F-15 pulls out of two Pratt & Whitney F-100-PW-220 engines.DAVID MCNEW//Getty Images

Lockheed Martin chose Pratt & Whitney to power their new stealth fighter, using an F135 engine derived from the F119 used in the F-22 Raptor. The powerful engine produces 40,000 pounds of thrust, just less than the F-15 pulls out of two Pratt & Whitney F-100-PW-220 engines.DAVID MCNEW//Getty Images

This approach, called “concurrency,” was meant to ship out F-35s sooner with plans to go back and correct identified issues later. Unfortunately, a long list of problems meant each of these early fighters needed massive overhauls that were often too pricey to pursue.

By 2010, nine years after Lockheed Martin was awarded the JSF contract, the cost per F-35 had ballooned to over 89 percent higher than initial estimates. It would still be another eight years before the first operational F-35s would get into the fight. To this day, the aircraft still hasn’t been approved for full-rate production, largely due to ongoing software issues.

Knowing Is Half the Battle

Cockpit instrumentation of the F-35 Lightning II.Richard Baker//Getty ImagesSo what really separates the pricey F-35 from the fighter jets that’ve come before it? Two words: data management.

Cockpit instrumentation of the F-35 Lightning II.Richard Baker//Getty ImagesSo what really separates the pricey F-35 from the fighter jets that’ve come before it? Two words: data management.

Today’s pilots have to manage a huge amount of information while flying, and doing so means splitting your time between traveling the speed of sound and a collage of screens, gauges, and sensor readouts screaming for your attention. Unlike previous fighter jets, the F-35 uses a combination of a heads-up display and helmet-based augmented reality to keep vital information directly in the pilot’s field of view.

Inside the F-35 Helmet

Nick Nacca

Nick Nacca

Every Gen III is customized to its owner’s head to prevent slippage during flight and to ensure that the displays appear in the correct locations. To do this, technicians scan each pilot’s head, mapping every feature and translating it into the helmet’s inner lining.

Pilots used to have to switch over to a mounted night-vision attachment when flying in the dark. The Gen III projects a night-vision reading of the surrounding environment directly onto the visor when the pilot switches the system on.

The shell is made of carbon fiber, which is what gives it a characteristic checkered pattern.

A tight coil of bound cables comes out of the back of the helmet to connect it to the plane, Matrix-style. When the wearer turns his head in a specific direction, the wires feed the helmet the proper camera footage.

The communications system has active noise cancellation. Speakers produce a sound that opposes wind noise and the low-frequency hum of the jet engines so pilots can hear clearly.

“In the F-16, each sensor was tied to a different screen… often the sensors would show contradictory information,” Lee tells Popular Mechanics. “The F-35 fuses everything into a green dot if it’s a good guy and a red dot if it’s a bad guy— it’s very pilot-friendly. All the information is shown on a panoramic cockpit display that is essentially two giant iPads.”

It’s not just how the information reaches the pilot, but also how it’s collected. The F-35 is capable of gathering information from a wide variety of sensors located on the aircraft and from information sourced from ground vehicles, drones, other aircraft, and nearby ships. It collects all of that information—as well as network-driven data about targets and nearby threats—and spits it all out into a single interface the pilot can easily manage while flying.

With a god’s eye view of the area, F-35 pilots can coordinate efforts with fourth-generation aircraft, making them deadlier in the process.

“In the F-35, we’re the quarterback of the battlefield—our job is to make everyone around us better,” says Lee. “Fourth-gen fighters like the F-16 and F-15 will be with us until at least the late 2040s. Because there are so many more of them than us, our job is to use our unique assets to shape the battlefield and make it more survivable for them.”

All of that information may sound daunting, but for fighter pilots who’ve experienced the demanding task of compiling information from a dozen different screens and gauges, the F-35’s user interface is nothing short of miraculous.

Tony “Brick” Wilson, who served in the U.S. Navy for 25 years prior to joining Lockheed Martin as a test pilot, has flown over 20 different aircraft, from helicopters to the U-2 spy plane and even a Russian MiG-15. According to him, the F-35 is—by far—the easiest aircraft to fly that he’s come across.

“As we moved into fourth-generation fighters like the F-16, we moved from being pilots to being sensor managers,” Wilson says. “Now, with the F-35, sensor fusion allows us to take some of that sensor management responsibility off the pilot’s hands, allowing us to be true tacticians.”

The Fighter of the Future

Matt Cardy//Getty Images

Matt Cardy//Getty Images

In May of 2018, the Israeli Defense Force became the first nation to send F-35s into combat, conducting two airstrikes with F-35As in the Middle East. By September of the same year, the U.S. Marine Corps sent their first F-35Bs into the fight, engaging ground targets in Afghanistan, followed by the U.S. Air Force using their F-35A’s for airstrikes in Iraq in April 2019.

Today, over 500 F-35 Lighting IIs have been delivered to nine nations and are operating out of 23 air bases around the world. That’s more than Russia’s fleet of fifth-generation Su-57s and China’s fleet of J-20s combined. With literally thousands more on order, the F-35 promises to be the backbone of U.S. air power.

And unlike previous fighter generations, the F-35’s capabilities are expected to keep up with the times. Thanks to software architecture designed to allow the F-35 to receive frequent updates, the aircraft’s form has stayed the same, but its function has already changed radically.

“The airplane that took that first flight back in 2006 may have looked identical on the outside, but it was a very different aircraft than the one we’re flying today,” Wilson says. “And the F-35 flying ten years from now is going to be very different from the one that we’re flying today.”

The F-35 will also serve as a test bed for technologies that will become commonplace in the next generation of jets. Flying in coordination with AI-enabled drones will become a staple of any sixth-generation fighter, and those new fighter tricks will likely first arrive in the form of the F-35.

“I look at the most capable, most connected, most survivable aircraft on the face of the planet and what we’re able to achieve with it today,” Wilson says. “I can only imagine what tomorrow’s F-35 is going to be capable of.”

Is it America’s most capable fighter, or America’s most expensive headache? Why not both?

Refueling under cover of darkness, a massive formation of U.S. Air Force, Royal Air Force, and Australian Air Force aircraft prepared for combat.

Fourth-generation fighters hailing from all three nations—including F-16 Fighting Falcons, F-15 Eagles, and Eurofighter Typhoons—coordinated with E-8 Joint STARS command-and-control aircraft. As their stealthy escorts, both F-22 Raptors and F-35 Joint Strike Fighters surveyed the battle space.

Soon, cockpit displays in each aircraft began to light up and alarms sounded, indicating that the formation was being painted by multiple radar arrays tied to surface-to-air missiles and inbound fighters. Enemy fighters sporting the color schemes of Russian Su-30s began to close in.

“On the last week of a Red Flag exercise we really throw everything we have at the Blue Force and replicate the toughest adversary possible,” says Travolis “Jaws” Simmons, commander of the 57th Adversary Tactics Group.

Ultimately, the F-35 fighter jet won the day, breaking down one of the world’s most advanced air defense networks and relaying the data to missile-packed fighters like the F-16.

The F-35 can fly at speeds as high as Mach 1.6 and can carry an internal payload of four weapons without compromising its stealth. But it’s not the F-35’s firepower that really makes the difference, it’s the computing power. It’s why F-35s have come to be known as “quarterbacks in the sky” or “a computer that happens to fly.”

“There has never been an aircraft that provides as much situational awareness as the F-35,” Major Justin “Hasard” Lee, an Air Force F-35 pilot instructor, tells Popular Mechanics. “In combat, situational awareness is worth its weight in gold.”

But for nearly its entire life, many have debated whether the F-35 is a game-changing platform or a case study in the excesses of the Pentagon’s weapon-acquisition process.

It turns out it’s both.

A 21st-Century Fighter Jet

The Boeing X-32, left, and the X-35 from Lockheed Martin.Joe McNally//Getty Images

The Boeing X-32, left, and the X-35 from Lockheed Martin.Joe McNally//Getty Images

The aircraft we know today as the F-35 was built to meet the demands of multiple fighting forces with a single, highly capable aircraft.

This new “Joint Strike Fighter,” Pentagon officials believed, would allow for streamlined logistical supply lines, maintenance, and training. It would also leverage the same stealth technologies found in the F-22.

With a laundry list of requirements from the U.S. Navy, Air Force, DARPA, and soon, the U.K. and Canada, the Joint Strike Fighter program quickly moved from its official proposal in 1995 to two competitive prototypes in 1997: Lockheed Martin’s X-35 and Boeing’s X-32. And the new fighter had its work cut out for it—the Joint Strike Fighter needed to replace at least five different aircraft across all the different services, including the high-speed interceptor F-14 Tomcat and the tank-killing close air support A-10 Thunderbolt II.

While replacing all these aircraft with one plane would (theoretically) save money, the long list of requirements led to a landslide of expensive complications. In fact, while the X-35 was still competing for the contract, many weren’t sure such an aircraft could even be built in significant numbers.

Lockheed Martin’s F-35: The Specs

A cross-section of the F-35 from the May 2002 issue of Popular Mechanics. Necessary design changes over the years likely altered these original design plans. Popular Mechanics / John Batchelor

A cross-section of the F-35 from the May 2002 issue of Popular Mechanics. Necessary design changes over the years likely altered these original design plans. Popular Mechanics / John Batchelor

Designed from the ground up to prioritize low-observability, the F-35 may be the stealthiest fighter in operation today. It uses a single F135 engine that produces 40,000 pounds of thrust with the afterburner engaged, capable of pushing the sleek but husky fighter to speeds as high as Mach 1.6. The aircraft can carry four weapons internally while flying in contested airspace, or can be outfitted with six additional weapons mounted on external hardpoints when flying in low-risk environments. The F-35A also comes equipped with an internal 4-barrel 25mm rotary cannon hidden behind a small door to minimize radar returns.

The standard weapons payload of all three F-35 variants includes two AIM-120C/D air-to-air missiles and two 1,000-pound GBU-32 JDAM guided bombs, allowing the F-35 to engage both airborne and ground-based targets. Lockheed Martin has developed a new internal weapons carriage that will eventually allow it to carry an additional two missiles internally.

The cockpit of the F-35 forgoes the litany of gauges and screens found in previous generations of fighter in favor of large touchscreens and a helmet mounted display system that allows the pilot to see real-time information. This helmet also allows the pilot to look directly through the aircraft, thanks to the F-35’s Distributed Aperture System (DAS) and suite of six infrared cameras mounted strategically around the aircraft.

“If you were to go back to the year 2000 and somebody said, ‘I can build an airplane that is stealthy and has vertical takeoff and landing capabilities and can go supersonic,’ most people in the industry would have said that’s impossible,” Tom Burbage, Lockheed’s general manager for the program from 2000 to 2013 told the New York Times. “The technology to bring all of that together into a single platform was beyond the reach of industry at that time.”

While both the X-32 and X-35 prototypes performed well, the deciding factor in the competition may have been the F-35’s complicated Short Take Off and Vertical Landing (STOVL) flight. Because the U.S. Marine Corps intended to use this new plane as a replacement for the AV-8B Harrier Jump Jets, America’s new stealth fighter had to be able to fill the same vertical landing, short take off role.

The Boeing X-32 prototypes were more unusual looking than its X-35 competition and in many ways, were less advanced. Boeing saw this as a selling point because the legacy systems leveraged in its design were cheaper to maintain. The aircraft used a direct-lift thrust vectoring system for vertical landings that was similar to that of the Harrier. It effectively just re-oriented the aircraft’s engine downward to lift the airframe, making it less stable than the X-35 in testing. But Boeing’s biggest mistake may have been the decision to field two prototypes: One that was capable of supersonic flight, and another that was capable of vertical landings. This decision left Pentagon officials worried about Boeing’s ability to field a single aircraft with all of those capabilities crammed inside a single fuselage. USAF//Wikimedia Commons

The Boeing X-32 prototypes were more unusual looking than its X-35 competition and in many ways, were less advanced. Boeing saw this as a selling point because the legacy systems leveraged in its design were cheaper to maintain. The aircraft used a direct-lift thrust vectoring system for vertical landings that was similar to that of the Harrier. It effectively just re-oriented the aircraft’s engine downward to lift the airframe, making it less stable than the X-35 in testing. But Boeing’s biggest mistake may have been the decision to field two prototypes: One that was capable of supersonic flight, and another that was capable of vertical landings. This decision left Pentagon officials worried about Boeing’s ability to field a single aircraft with all of those capabilities crammed inside a single fuselage. USAF//Wikimedia Commons

The lift fan design used in the X-35 connected the engine at the back of the aircraft to a drive shaft that would power a large fan installed in the aircraft’s fuselage behind the pilot. When hovering, the F-35 would orient its engine downward, not unlike the X-32, but it would also pull air from above the aircraft and force it down through the fan and out the bottom, creating two balanced sources of thrust that made the aircraft far more stable.

It also helped the F-35 notch a win in the looks category.

“You can look at the Lockheed Martin airplane and say, that looks like what I would expect a modern, high performance, high capable jet fighter to look like,” Lockheed Martin engineer Rick Rezebek says in a PBS Nova episode. “You look at the Boeing airplane and the general reaction is, ‘I don’t get it.’”

Ultimately, Lockheed Martin won out over Boeing’s unusual looking X-32 prototype in October of 2001. The future looked bright for the newly named F-35.

Complications and Headaches

The F-35 receives a robotic spray of radar-baffling coating along the leading edge of its wing and air intake.Popular Mechanics / Randy A. Crites

The F-35 receives a robotic spray of radar-baffling coating along the leading edge of its wing and air intake.Popular Mechanics / Randy A. Crites

While Lockheed’s lift fan approach to STOVL flight might’ve nabbed the contract, the hard part was just beginning.

Choosing to begin with the least complex iteration of the new fighter, Lockheed’s Skunk Works started designing the F-35A, intended for use in the U.S. Air Force as a traditional runway fighter like the F-16 Fighting Falcon. Once the F-35A was complete, the engineering team would then move on to the more complex STOVL F-35B for use by the U.S. Marine Corps, and then, finally, the F-35C meant for carrier duty.

There was just one problem—jamming all the necessary hardware for the different variants into a single fuselage proved extremely difficult. By the time Lockheed Martin wrapped up design work on the F-35A and got to work on the B, they realized the weight estimates they had established while designing the Air Force variant would lead to an aircraft that was 3,000 pounds too heavy. This miscalculation created a significant setback—the first of many.

Meet the F-35 Variants

To the outside observer, the differences between each F-35 variant can be difficult to detect— and for good reason. The only real differences among each iteration of the jet are related to basing requirements. In other words, the most noticeable differences are in how the fighter takes off and lands.

F-35A

F-35A

Intended for use by the U.S. Air Force and many allied nations, the F-35A is the conventional take off and landing (CTOL) variant. This aircraft is intended to operate out of traditional airstrips and is the only version of the F-35 to come equipped with a 25mm internal cannon, allowing it to step in for both the F-16 multirole fighter and the flying cannon A-10 Thunderbolt II, among many others.

F-35B

F-35B

The F-35B was purpose-built for short take off and vertical landing operations (STOVL) and was designed with the needs of the U.S. Marine Corps in mind. While still able to operate off of traditional runways, the STOVL capability offered by the F-35B allows Marines to operate these jets from austere runways or off the decks of amphibious assault ships, often referred to as “Lightning Carriers.”

F-35C

F-35C

The F-35C is the first stealth fighter ever designed for carrier operations with the U.S. Navy. It boasts larger wings than its peers, to allow for slower approach speeds when landing on a carrier. More robust landing gear aids in tough carrier landings, and it harbors a larger fuel supply (20,000 pounds’ worth) internally to support longer range missions. The C is also the only F-35 equipped with folding wings, allowing for easier storage in the hull of ships.

“It turns out when you combine the requirements of the three services, what you end up with is the F-35, which is an aircraft that is in many ways suboptimal for what each of the services really want,” Todd Harrison, an aerospace expert with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the New York Times in 2019.

Lockheed Martin’s team would eventually work out the finer points of each different platform, leaving as much of the aircraft consistent across branches as possible. But pulling off this engineering magic trick led to a series of delays and cost overruns.

Lockheed Martin’s bad arithmetic in the weight category stretched early development by 18 months and cost a daunting $6.2 billion to correct, but it was just the first of many issues to plague the new Joint Strike Fighter. It wouldn’t be until February of 2006, five years after Lockheed won the contract, that the first F-35A would roll off the assembly line. But these early F-35s weren’t even ready to fight because the Pentagon had chosen to begin production before they had completed testing.

Lockheed Martin chose Pratt & Whitney to power their new stealth fighter, using an F135 engine derived from the F119 used in the F-22 Raptor. The powerful engine produces 40,000 pounds of thrust, just less than the F-15 pulls out of two Pratt & Whitney F-100-PW-220 engines.DAVID MCNEW//Getty Images

Lockheed Martin chose Pratt & Whitney to power their new stealth fighter, using an F135 engine derived from the F119 used in the F-22 Raptor. The powerful engine produces 40,000 pounds of thrust, just less than the F-15 pulls out of two Pratt & Whitney F-100-PW-220 engines.DAVID MCNEW//Getty Images

This approach, called “concurrency,” was meant to ship out F-35s sooner with plans to go back and correct identified issues later. Unfortunately, a long list of problems meant each of these early fighters needed massive overhauls that were often too pricey to pursue.

By 2010, nine years after Lockheed Martin was awarded the JSF contract, the cost per F-35 had ballooned to over 89 percent higher than initial estimates. It would still be another eight years before the first operational F-35s would get into the fight. To this day, the aircraft still hasn’t been approved for full-rate production, largely due to ongoing software issues.

Knowing Is Half the Battle

Cockpit instrumentation of the F-35 Lightning II.Richard Baker//Getty ImagesSo what really separates the pricey F-35 from the fighter jets that’ve come before it? Two words: data management.

Cockpit instrumentation of the F-35 Lightning II.Richard Baker//Getty ImagesSo what really separates the pricey F-35 from the fighter jets that’ve come before it? Two words: data management.

Today’s pilots have to manage a huge amount of information while flying, and doing so means splitting your time between traveling the speed of sound and a collage of screens, gauges, and sensor readouts screaming for your attention. Unlike previous fighter jets, the F-35 uses a combination of a heads-up display and helmet-based augmented reality to keep vital information directly in the pilot’s field of view.

Inside the F-35 Helmet

Nick Nacca

Nick Nacca

Every Gen III is customized to its owner’s head to prevent slippage during flight and to ensure that the displays appear in the correct locations. To do this, technicians scan each pilot’s head, mapping every feature and translating it into the helmet’s inner lining.

Pilots used to have to switch over to a mounted night-vision attachment when flying in the dark. The Gen III projects a night-vision reading of the surrounding environment directly onto the visor when the pilot switches the system on.

The shell is made of carbon fiber, which is what gives it a characteristic checkered pattern.

A tight coil of bound cables comes out of the back of the helmet to connect it to the plane, Matrix-style. When the wearer turns his head in a specific direction, the wires feed the helmet the proper camera footage.

The communications system has active noise cancellation. Speakers produce a sound that opposes wind noise and the low-frequency hum of the jet engines so pilots can hear clearly.

“In the F-16, each sensor was tied to a different screen… often the sensors would show contradictory information,” Lee tells Popular Mechanics. “The F-35 fuses everything into a green dot if it’s a good guy and a red dot if it’s a bad guy— it’s very pilot-friendly. All the information is shown on a panoramic cockpit display that is essentially two giant iPads.”

It’s not just how the information reaches the pilot, but also how it’s collected. The F-35 is capable of gathering information from a wide variety of sensors located on the aircraft and from information sourced from ground vehicles, drones, other aircraft, and nearby ships. It collects all of that information—as well as network-driven data about targets and nearby threats—and spits it all out into a single interface the pilot can easily manage while flying.

With a god’s eye view of the area, F-35 pilots can coordinate efforts with fourth-generation aircraft, making them deadlier in the process.

“In the F-35, we’re the quarterback of the battlefield—our job is to make everyone around us better,” says Lee. “Fourth-gen fighters like the F-16 and F-15 will be with us until at least the late 2040s. Because there are so many more of them than us, our job is to use our unique assets to shape the battlefield and make it more survivable for them.”

All of that information may sound daunting, but for fighter pilots who’ve experienced the demanding task of compiling information from a dozen different screens and gauges, the F-35’s user interface is nothing short of miraculous.

Tony “Brick” Wilson, who served in the U.S. Navy for 25 years prior to joining Lockheed Martin as a test pilot, has flown over 20 different aircraft, from helicopters to the U-2 spy plane and even a Russian MiG-15. According to him, the F-35 is—by far—the easiest aircraft to fly that he’s come across.

“As we moved into fourth-generation fighters like the F-16, we moved from being pilots to being sensor managers,” Wilson says. “Now, with the F-35, sensor fusion allows us to take some of that sensor management responsibility off the pilot’s hands, allowing us to be true tacticians.”

The Fighter of the Future

Matt Cardy//Getty Images

Matt Cardy//Getty Images

In May of 2018, the Israeli Defense Force became the first nation to send F-35s into combat, conducting two airstrikes with F-35As in the Middle East. By September of the same year, the U.S. Marine Corps sent their first F-35Bs into the fight, engaging ground targets in Afghanistan, followed by the U.S. Air Force using their F-35A’s for airstrikes in Iraq in April 2019.

Today, over 500 F-35 Lighting IIs have been delivered to nine nations and are operating out of 23 air bases around the world. That’s more than Russia’s fleet of fifth-generation Su-57s and China’s fleet of J-20s combined. With literally thousands more on order, the F-35 promises to be the backbone of U.S. air power.

And unlike previous fighter generations, the F-35’s capabilities are expected to keep up with the times. Thanks to software architecture designed to allow the F-35 to receive frequent updates, the aircraft’s form has stayed the same, but its function has already changed radically.

“The airplane that took that first flight back in 2006 may have looked identical on the outside, but it was a very different aircraft than the one we’re flying today,” Wilson says. “And the F-35 flying ten years from now is going to be very different from the one that we’re flying today.”

The F-35 will also serve as a test bed for technologies that will become commonplace in the next generation of jets. Flying in coordination with AI-enabled drones will become a staple of any sixth-generation fighter, and those new fighter tricks will likely first arrive in the form of the F-35.

“I look at the most capable, most connected, most survivable aircraft on the face of the planet and what we’re able to achieve with it today,” Wilson says. “I can only imagine what tomorrow’s F-35 is going to be capable of.”

The Boeing X-32, left, and the X-35 from Lockheed Martin.Joe McNally//Getty Images

The Boeing X-32, left, and the X-35 from Lockheed Martin.Joe McNally//Getty Images A cross-section of the F-35 from the May 2002 issue of Popular Mechanics. Necessary design changes over the years likely altered these original design plans. Popular Mechanics / John Batchelor

A cross-section of the F-35 from the May 2002 issue of Popular Mechanics. Necessary design changes over the years likely altered these original design plans. Popular Mechanics / John Batchelor The Boeing X-32 prototypes were more unusual looking than its X-35 competition and in many ways, were less advanced. Boeing saw this as a selling point because the legacy systems leveraged in its design were cheaper to maintain. The aircraft used a direct-lift thrust vectoring system for vertical landings that was similar to that of the Harrier. It effectively just re-oriented the aircraft’s engine downward to lift the airframe, making it less stable than the X-35 in testing. But Boeing’s biggest mistake may have been the decision to field two prototypes: One that was capable of supersonic flight, and another that was capable of vertical landings. This decision left Pentagon officials worried about Boeing’s ability to field a single aircraft with all of those capabilities crammed inside a single fuselage. USAF//Wikimedia Commons

The Boeing X-32 prototypes were more unusual looking than its X-35 competition and in many ways, were less advanced. Boeing saw this as a selling point because the legacy systems leveraged in its design were cheaper to maintain. The aircraft used a direct-lift thrust vectoring system for vertical landings that was similar to that of the Harrier. It effectively just re-oriented the aircraft’s engine downward to lift the airframe, making it less stable than the X-35 in testing. But Boeing’s biggest mistake may have been the decision to field two prototypes: One that was capable of supersonic flight, and another that was capable of vertical landings. This decision left Pentagon officials worried about Boeing’s ability to field a single aircraft with all of those capabilities crammed inside a single fuselage. USAF//Wikimedia Commons The F-35 receives a robotic spray of radar-baffling coating along the leading edge of its wing and air intake.Popular Mechanics / Randy A. Crites

The F-35 receives a robotic spray of radar-baffling coating along the leading edge of its wing and air intake.Popular Mechanics / Randy A. Crites F-35A

F-35A F-35B

F-35B F-35C

F-35C Lockheed Martin chose Pratt & Whitney to power their new stealth fighter, using an F135 engine derived from the F119 used in the F-22 Raptor. The powerful engine produces 40,000 pounds of thrust, just less than the F-15 pulls out of two Pratt & Whitney F-100-PW-220 engines.DAVID MCNEW//Getty Images

Lockheed Martin chose Pratt & Whitney to power their new stealth fighter, using an F135 engine derived from the F119 used in the F-22 Raptor. The powerful engine produces 40,000 pounds of thrust, just less than the F-15 pulls out of two Pratt & Whitney F-100-PW-220 engines.DAVID MCNEW//Getty Images Cockpit instrumentation of the F-35 Lightning II.Richard Baker//Getty ImagesSo what really separates the pricey F-35 from the fighter jets that’ve come before it? Two words: data management.

Cockpit instrumentation of the F-35 Lightning II.Richard Baker//Getty ImagesSo what really separates the pricey F-35 from the fighter jets that’ve come before it? Two words: data management. Nick Nacca

Nick Nacca Matt Cardy//Getty Images

Matt Cardy//Getty Images

F-14 Tomcat. Image taken at National Air and Space Museum on October 1, 2022. Image by 19FortyFive.

F-14 Tomcat. Image taken at National Air and Space Museum on October 1, 2022. Image by 19FortyFive. F-14 Tomcat. Image taken at National Air and Space Museum on October 1, 2022. Image by 19FortyFive.

F-14 Tomcat. Image taken at National Air and Space Museum on October 1, 2022. Image by 19FortyFive. F-14 Tomcat. Image taken at National Air and Space Museum on October 1, 2022. Image by 19FortyFive.

F-14 Tomcat. Image taken at National Air and Space Museum on October 1, 2022. Image by 19FortyFive. F-14 Tomcat. Image Taken at U.S. Air and Space Museum outside of Washington, D.C. Image Credit: 19FortyFive.com

F-14 Tomcat. Image Taken at U.S. Air and Space Museum outside of Washington, D.C. Image Credit: 19FortyFive.com