Mary Beard is the best boss I’ve ever had. She was head of the Faculty of Classics at Cambridge when I worked there for a year. She welcomed me when I arrived, told people to read my then-new book (the first one, The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt), and let me get on with my job in the Museum of Classical Archaeology. Heaven.

So like any right-thinking person, I’ve been appalled by the vitriolic attacks made on her via Twitter the past week or two, after she expressed support for the way a BBC educational cartoon – yes, for children – showed a high-ranking Roman family in Britain that included a dark-skinned father and a literate mother. (Read about it in her own words here, plus lots of press coverage and some top-notch science journalism out there in response.) Both a Roman officer from Africa and a Roman woman who could read and write are unusual, but they are not unattested. Besides which, one aim was to show children today that there was diversity in the ancient world. To paint back in some of the people who have been painted out for a long time. Similar things have been done with educational material in the UK and US (maybe elsewhere, too) to ensure that ancient Egypt isn’t white-washed.

And for a third, Egypt is a place of in-betweenness, or so it seemed from Europe’s vantage point: in between Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean, to use modern Western conceptions of those spaces. That makes ancient Egypt ‘unstable’, in slightly fancy academic talk. The unstable things are what everyone’s trying to prop up or topple down, over and over again, a bit like poking a bruise.

If we go back to the 18th century, we can see how race was invented to characterize physical differences between humans, and then developed in a way that supported crippling inequalities based on those perceived differences. One of the least pleasant bits of research I’ve ever done was reading a book called Types of Mankind, written by self-professed Egyptologist George Gliddon and a slave-owning doctor named Josiah Nott. It’s vile in its long-winded justification of racism, but that didn’t stop it going into eight printings in 1850s America. Nor can we dismiss people like Gliddon and Nott as cranks. Race science wasn’t a pseudo-science – a word that might seem to create some safe distance between ‘us’ in the 21st century and earlier scholars who accepted, furthered, and used its core principles. It was the real deal, and every archaeologist and anthropologist trained in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had been trained to understand the ancient past through some version of racial categorization.**

So, inevitably, to Tutankhamun. By the time the mummy was unwrapped – or rather, cut through, scraped away, and taken to pieces – the principles of racial classification were always, always applied to ancient Egyptian human remains. That meant getting a medical doctor to take a series of measurements of the skull and of major bones, too, if the body was dissected or poorly preserved within the wrappings, as Tutankhamun’s was. At the unwrapping of Tutankhamun’s mummy in November 1925, there were two medical doctors on hand to study it, Douglas Derry, professor of anatomy at the Cairo Medical School, and Saleh Bey Hamdi, its former head. Only Derry was credited on the published anatomical report, which duly reported all the skeletal measurements.^

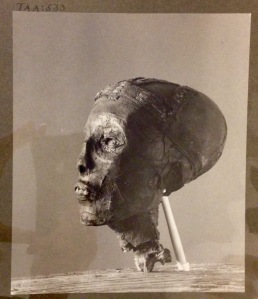

Only two photographs of the head of Tutankhamun’s mummy were published at the time – both with the head cradled in a white cloth, which concealed the fact that it had been detached from the body at the bottom of the neck in order to remove the gold mummy mask. The cloth also conceals all the tools and detritus on the work surface, which is clear on the photographic negatives. They were printed and published cropped to the head itself with the cloth around it, as you see here:

Left profile of the mummified head of Tutankhamun, photograph by Harry Burton (neg. TAA 553), as published in The Illustrated London News, 1926.

(Personal disclaimer here: I really, really hate publishing photographs of mummies, especially unwrapped mummies, mummified body parts, and children’s mummies. I’ve done it here to make a larger point about the visualization of race – and I know these images are already circulating out there. Still, uneasy about it.)

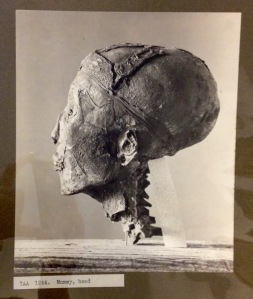

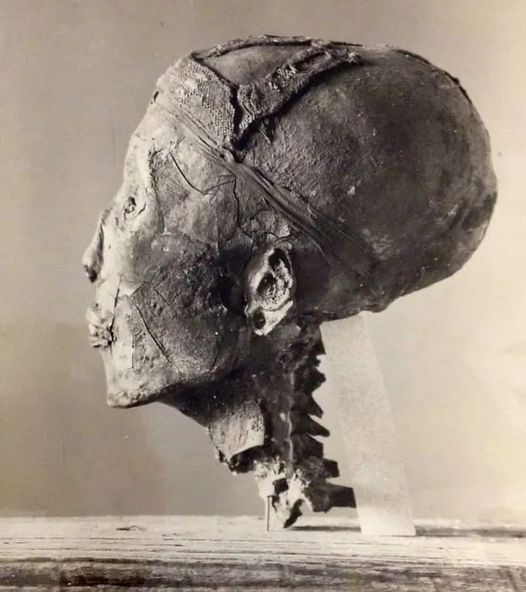

Anyway, of the two photographs that Howard Carter released to the press and used in his own book on Tutankhamun (volume 2), there were two views, one to the front and one to show the left profile, as you see above. But photographer Harry Burton took several more photographs of the head after a little more work had been done on it – and after it had been mounted upright on a wooden plank, with what looks the handle of a paintbrush used to prop up the neck. None of these photographs were published in Carter’s (or Burton’s) lifetimes, and I don’t think they were meant to be. But clearly, from their perspective, having photographs of the head was crucial. It’s also telling that while some of the photographs show the head at near-profile or three-quarter angles, most stick to the established norms of racial ‘type’ photography: front, back, left profile, right profile.

Print, possibly from 1925, of a photograph by Harry Burton, from neg. TAA 553, (c) The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Above, an example of one of the near-profile or three-quarter angle views. As far as I can tell, this was first published, at a size even smaller than the image here, in Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt’s English-language book Tutankhamun (George Rainbird 1963) – with the paintbrush handle carefully erased. (Here, you just get my iPhone reflection.)

Print of a photograph by Harry Burton, from neg. TAA 1244, (c) The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The paintbrush handle has been masked out with tape.

It wasn’t until 1972 that most or all of the photographs of the mummy, including its head, were published in a scholarly study by F. Filce Leek, part of the Griffith Institute’s Tutankhamun’s Tomb monograph series. That included the left profile above, where masking tape was applied to the negative before printing – again, to remove the paintbrush handle.

These different stagings of the head of Tutankhamun’s mummy matter, likewise the way the photographs did or didn’t circulate, or what adaptations were deemed necessary to make them presentable for publication. Clearly, that paintbrush handle was deemed inappropriate in some way in the 1960s – just as in the 1920s and 1930s, when Carter was still writing about the tomb, he must have deemed it inappropriate to show that second set of photographs at all.

And what do they show us, these photographs? The face of Tutankhamun? The race of Tutankhamun? Or something else? Carter didn’t explicitly discuss race when he described the mummy’s appearance: he didn’t have to, because there was already a code in language to distinguish more ‘Caucasian’ bodies from more ‘Negroid’ ones (to use the most common terms deployed in late 19th-/early 20th-century archaeology). ‘The face is refined and cultured’, so the Illustrated London News reported in its 3 July 1926 edition, almost certainly closely paraphrasing or directly quoting Carter. Placed underneath the cloth-wrapped left profile (the first photo I showed above), text and picture together made it clear enough to the paper’s middle-class readers that Tutankhamun was an ancient Egyptian of more Arab, Turkish, or even European appearance than sub-saharan African. The mummy’s sunken cheekbones seem high and sharp, and the crushed nose in profile looks high-bridged and narrow.

What really interests me here, though, is what we don’t see, because we still take such photographs, and drawings, and CT-scans, and 3D reconstructions, for granted: images like these have race science at their very heart, going right back to the 18th century.^^ So when I see a photograph like this – and there are thousands of them in the annals of archaeology – I don’t see Tutankhamun, and I certainly don’t see anything refined or cultured about mummified heads. I see the extent to which the doing of race had worked its way into pretty much every corner of archaeology, especially in the archaeology of colonized and contentious lands like Egypt. Why take these photographs? I assume that in 1925, it was inconceivable not to, just as it was inconceivable not to unwrap the mummy, not to take anatomical measurements, and not to detach the head from the body and pry it out of the mask.

Pictures matter, photographs matter, and the way we use photographs and talk about photographs, those matter too. In the book I’ll be publishing next year on the photographic archive of Tutankhamun’s tomb, I go into more detail about this particular set of photographs of the mummified head. But given the controversy over race, skin colour, and DNA in Roman Britain that flared up recently, I thought I’d get back into blog writing with this example.

In our image-saturated age, we need to be even more careful about how we use historic images like these photographs. Don’t look at what they show in the picture. Look instead for what they show about the mindsets and motivations behind the taking of the picture. The legacies of race science are still with us – and if, as archaeologists, historians, or Egyptologists, we want a wider public to understand those legacies, we need much more vocal and more critical work on the history of Egyptology and the visualization of the ancient dead.

NOTES

* I talk a bit about the problem with the word ‘civilization’ in a book called (yes, the irony) Egypt: Lost Civilizations (Reaktion 2017). Scott Trafton does a fantastic job talking about how African-Americans perceived ancient Egypt in the 19th century – sometimes as their own place of origin, to take pride in a chapter of African history, but sometimes as a place of slavery, to be rejected in the struggle against slavery. His book is called Egypt Land, and I learned a lot from it. Great cover, too.

** For how race infused the study of archaeology, see Debbie Challis’s excellent The Archaeology of Race (Bloomsbury 2015), and for its impact on the study of ancient Mesopotamia, I can’t recommend Jean Evans, The Lives of Sumerian Sculpture (Cambridge UP 2012) highly enough.

^ On this exclusion, see Donald Malcolm Reid, Contesting Antiquity in Egypt (American University in Cairo Press 2015), pp. 56-8.

^^ My take on this, with lots of further references: ‘An autopsic art: Drawings of “Dr Granville’s mummy’ in the Royal Society archives’, Royal Society Notes and Records 70.2 (2016), Open Access here. There’s a vast literature on photography and race, especially in visual anthropology but also history of science/medicine. Two good starting points: Deborah Poole, Vision, Race, and Modernity (Princeton UP 1997) and Amos Morris-Reich, Race and Photography (Chicago UP 2016 – talk about having to read some stomach-churning stuff for research…).

Shutterstock.

Shutterstock. Shutterstock.

Shutterstock. The Bent Pyramid is also known as the False, or Rhomboidal Pyramid because of its changed angle slope.. Shutterstock.

The Bent Pyramid is also known as the False, or Rhomboidal Pyramid because of its changed angle slope.. Shutterstock.