A number of machine guns saw action during the First World War. While the Vickers, Maxim and Lewis guns are likely the ones that come to mind, there’s another that stands out simply because of how unusual its design was: the Schwarzlose MG. Developed for the Austro-Hungarian Army, this machine gun not only saw use by infantrymen, but was adapted to feature aboard ships and on aircraft, and was even installed in military fortifications.

Development of the Schwarzlose MG

The Schwarzlose MG, also known as the Maschinengewehr M, was designed in 1904 by Prussian firearms designer Andreas Wilhelm Schwarzlose, who rose to fame for developing a blowback-operated machine gun. The weapon entered production in 1905 as the M1905, and was steadily improved upon as the years went on.

The Schwarzlose used by soldiers during World War I entered production in 1908 and was manufactured by Steyr Arms and Fegyver-és-Gépgyár (FÉG) for a decade. In 1918, active sales of the weapon ended with the close of the conflict.

Schwarzlose MG specs

The Schwarzlose MG was a belt-fed, water-cooled machine gun that resembled those within the Maxim family. However, it was given a much simpler design and function, meaning it was inexpensive to manufacture, allowing for the necessary quantities to be produced during the First World War.

While resembling the Maxim, the Schwarzlose was unusual in that it employed a delayed blowback mechanism that utilized a single spring, as well as another that incorporated a device that oiled cartridge cases for easier extraction. The former feature allowed the chamber pressure to drop to a safe level, if the machine gun was operated correctly.

Use as an infantry weapon

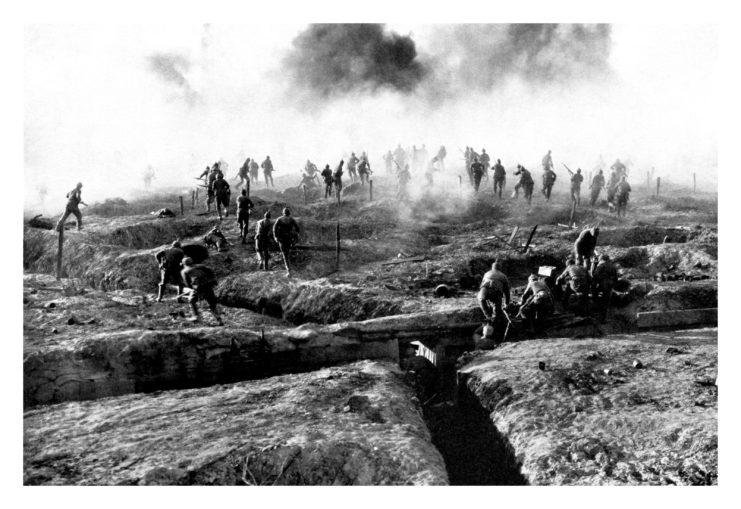

The Schwarzlose MG was developed for use by infantrymen and thus was used heavily throughout the fighting that occurred during the First World War. It served a traditional, tripod-mounted role, with a crew of three typically charged with manning it. One served as the commander, while the others were the gunner and ammunition carrier. The third would also typically act as the loader.

While serving as an infantry weapon, the Schwarzlose could also be deployed with a more-compact “backpack mount,” although it was rarely used in such a way. In this configuration, it was fitted with a backwards folding bipod that was attached to the front of the water jacket, near the muzzle.

Modifying the Schwarzlose MG for aircraft was a challenge

While the Schwarzlose MG was used by infantrymen in an anti-aircraft capacity, it was actually adapted for use by aircraft flown by the Austro-Hungarian k.u.k. Luftfahrtruppe. A lighter version was necessary for this, which was ring-mounted or fixed-wing.

Right away, it was evident the Schwarzlose wasn’t developed for use by aircraft, as synchronizing it proved to be an engineering nightmare, due to the weapon’s delayed blowback mechanism. To bypass this, the fighters were equipped with large tachometers and Kravics indicators, which warned pilots of malfunctions in the synchronization gear. Attached through electrical wiring, they knew something was wrong when the Kravics’ light went out.

Increasing the defense of military fortifications

Outside of its aforementioned roles, the Schwarzlose MG also saw use as a naval gun aboard sea vessels and a fortress weapon. When equipped for the latter, it could be deployed on a host of different fixed mountings.

While its use as a fortress weapon was limited during WWI, the Czechoslovakians used the Schwarzlose in this capacity during the interwar period. The country’s armed forces adapted the machine gun, tasked the Janeček Factory with production and renamed it the těžký kulomet vz. 7/24.

Issues with the Schwarzlose MG

While the Schwarzlose MG was effective as an infantry weapon, it did have issues, particularly when used in ways it hadn’t been designed for, such as its aforementioned role as an aircraft gun. Outside of this, its unlocked-breech design required a shorter barrel, which, while helping to alleviate pressure, limited the machine gun’s muzzle velocity and reach. It also created a significant muzzle flash, necessitating the use of a rather large flash suppressor.

Another issue involved the Schwarzlose’s reliance on the weight of its breech block and semi-folded toggle arm. The former would unfold at a severe mechanical disadvantage, thereby slowing down the opening of the former.

Use by other nations

Outside of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Schwarzlose MG saw use by a number of nations, including Greece, the Ottoman Empire, the Netherlands, Imperial Russia and Sweden, to name a few. During the interwar period, the Polish Air Force equipped its aircraft with the machine guns, using them against the Soviets during the Polish-Soviet War, while Japan equipped the 6.5 mm Arisaka variant on its Fusō-class battleships and Kongō-class battlecruisers.

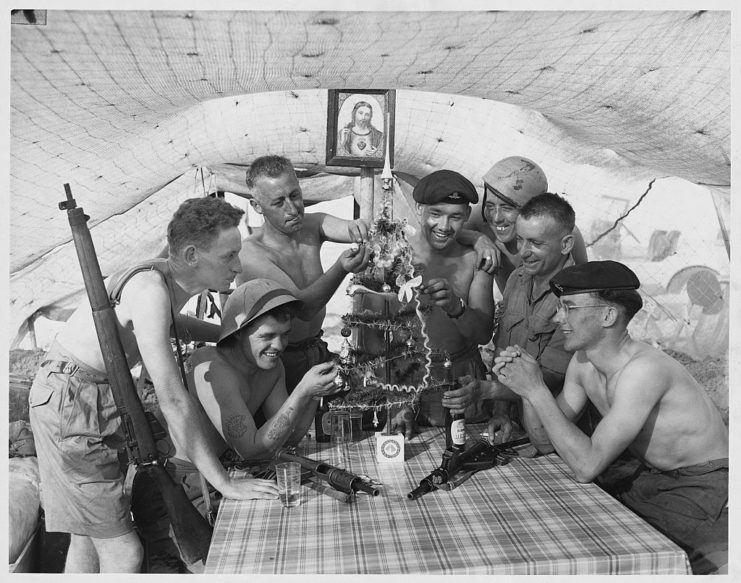

When World War II broke out, the Schwarzlose was the standard-issue machine gun for the Italian colonial forces stationed in North Africa, where it saw limited action as an anti-aircraft weapon. The German Army also used it during the final stages of the conflict, while the Swedish volunteer unit (SFK) equipped it during the Winter War.

Before it became obsolete, the Schwarzlose also saw use during the 1932-33 Colombia-Peru War, the Russian Civil War, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the Austro-Slovene Conflict, the Balkan Wars, the Spanish Civil War and the Austrian Civil War.