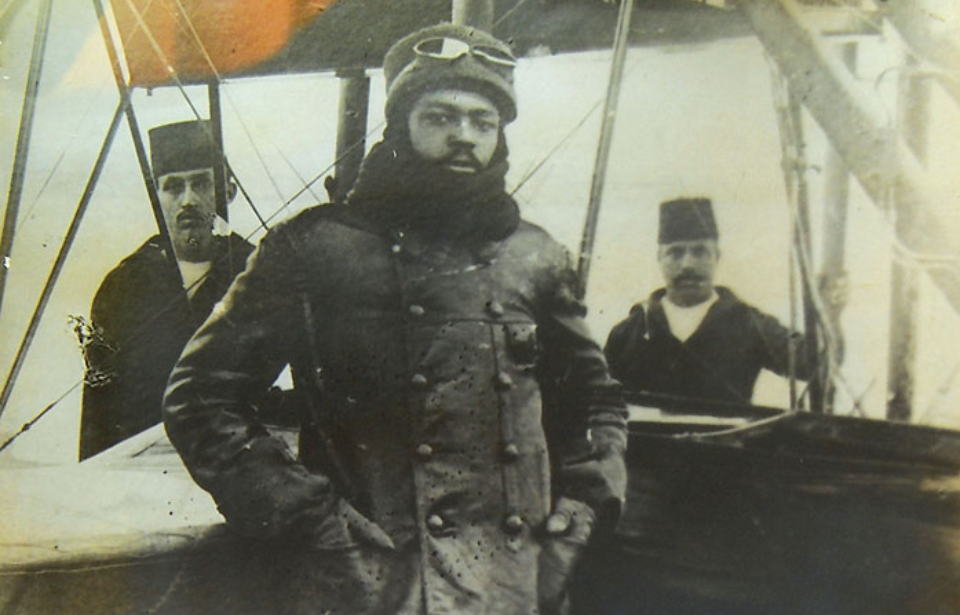

Exactly two years before World War I came to an end, Ahmet Ali Çelikten became one of the world’s first Black military aviators. Çelikten, who retired from the Turkish Air Force as a colonel in 1949, set the stage for future mixed-race fighter pilots and Black excellence within militaries around the world.

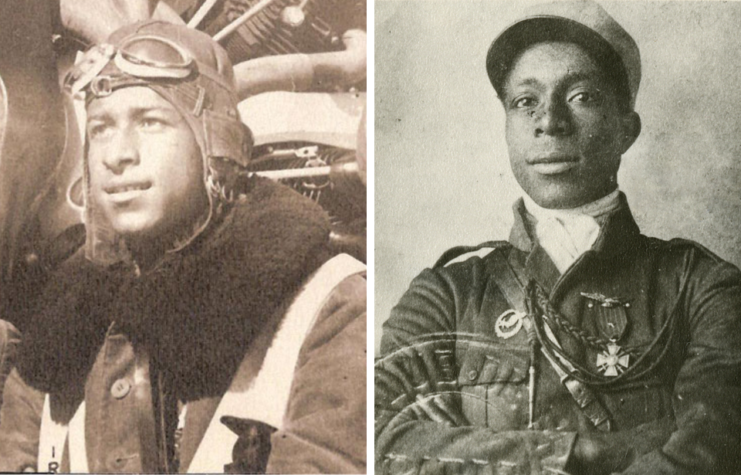

Ahmet Ali Çelikten’s undergoes flight training

Ahmet Ali Çelikten was born in the Ottoman Empire in 1883. As a young man, he dreamed of becoming a sailor, and enrolled in the naval technical school Haddehâne Mektebi to make that aspiration a reality. He graduated in 1908 as a first lieutenant.

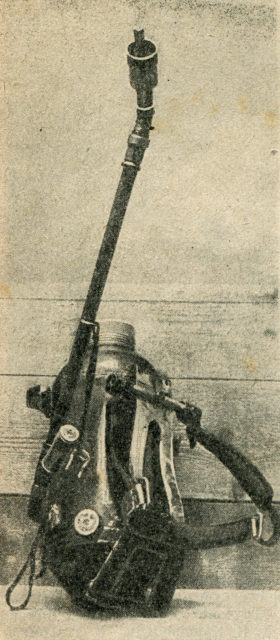

On February 20, 1914, Çelikten became the first Black pilot to ever receive a license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. He subsequently attended the naval flight school Mülâzım-ı evvel in Yeşilköy, a neighborhood of Istanbul.

The Ottoman Empire’s role in World War I

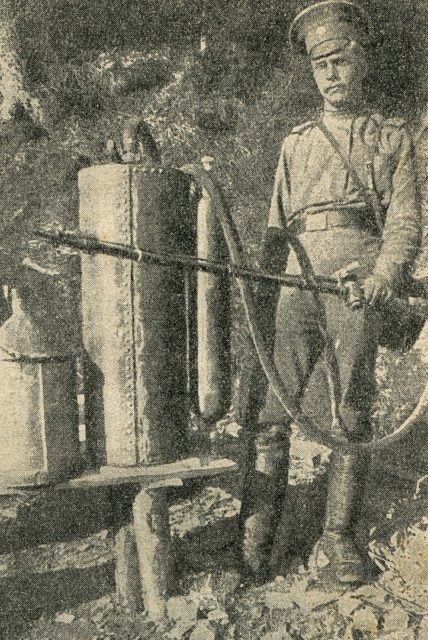

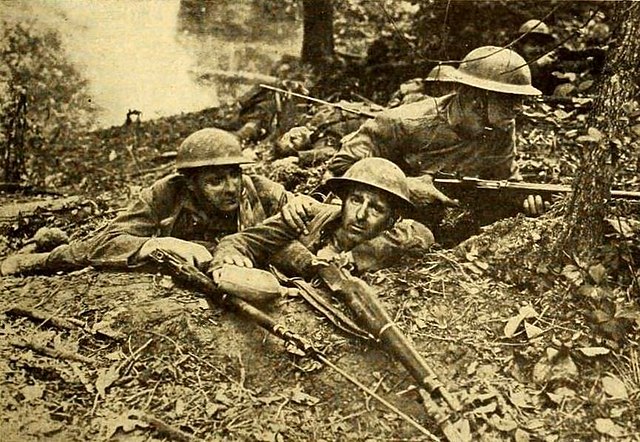

Though they are often left out of the picture, the Ottoman Army fought throughout the First World War. Comprised of individuals from all walks of life, races and ethnicities, the Ottomans served the Sultan, protected their homeland and, ultimately, worked to construct a new nation as the Empire collapsed for good.

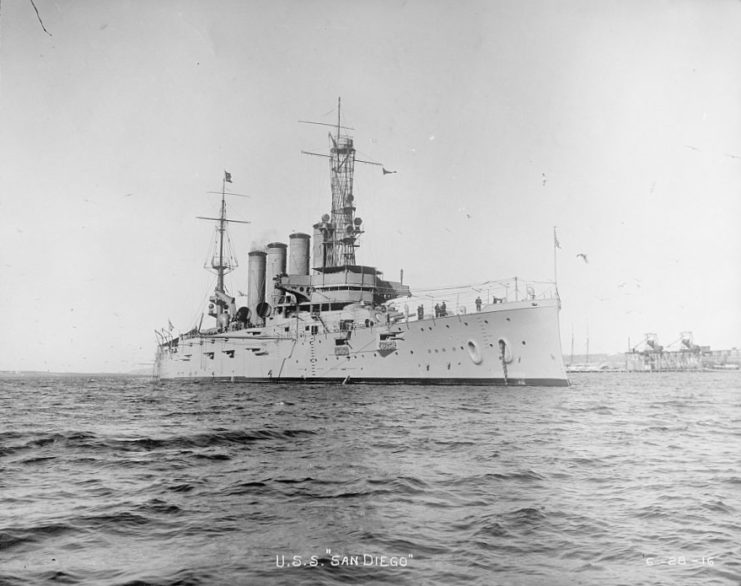

The Ottomans entered WWI following the Black Sea Raid on October 29, 1914, not long after the start of the conflict. They and Germany created an alliance to allow the latter safe passage into nearby British colonies.

The Balkan Wars in the years prior had depleted Ottoman resources, and their dependence on agriculture was slowly becoming threatened by escalating industrial warfare. Shortly after entering the war, Sultan Mehmed V declared a state of Jihad (meaning meritorious struggle or effort) against the countries that made up the Triple Entente.

Ahmet Ali Çelikten became a freedom fighter

During WWI, Ahmet Ali Çelikten married Hatice Hanim, a Greek woman who’d immigrated from Preveza. Following his military service, he became involved in the Turkish War of Independence, volunteering with the Turkish National Movement at Konya Military Air Base.

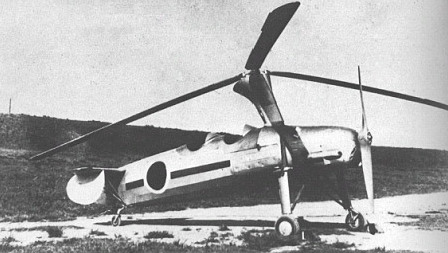

At the time, Turkish freedom fighters plotted to steal aircraft from Ottoman-owned warehouses and bring them to a location on the Black Sea. Çelikten was recruited to aid in this mission in 1922. The stolen aircraft were subsequently used to protect various Nationalist naval operations and monitor enemy movements along the body of water.

An inspiring legacy

By the time he retired in 1949, Ahmet Ali Çelikten was a colonel in the Turkish Air Force. He quietly lived out the rest of his days with his family, and died on June 24, 1969. He inspired several of his family members to serve in the Air Force. His two sons, two daughters, niece and nephew all became pilots, and several grandchildren adopted his love of flight, working in Turkey’s aviation industry.