Given the numerous theaters American aircraft flew in throughout World War II, it’s no wonder the majority suffered extensive damage at the hands of the enemy. The following photos show the destruction sustained by various aircraft while in combat, as well as details regarding just how the Americans went about constructing and repairing their aerial vehicles, from production to secret operations.

Production of American aircraft during World War II

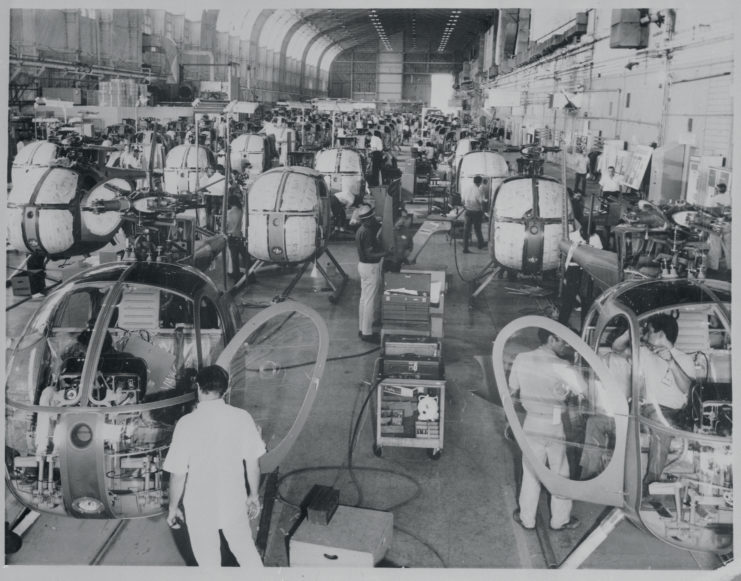

American assembly lines during World War II were impressive in all areas, but none more so than in the aircraft sector. Although the United States was manufacturing its own aircraft before the conflict began, it increased production to an impressive rate from 1939-45.

In 1939, the US produced 3,000 aircraft, and by the end of World War II, 300,000 had left assembly lines. Over the course of just six years, the country’s aircraft industry became its most productive sector, in part because automobile manufacturers changed their day-to-day to support the war effort. They did this by producing various aircraft parts.

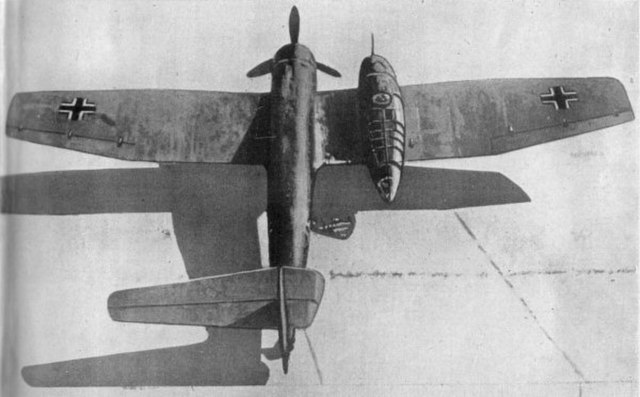

Most notably, America produced the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and B-29 Superfortress, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and the North American P-51 Mustang. All were heavily used in each theater of the war.

“Keeping them flying”

Ground crews were instrumental in maintaining the many types of American aircraft flown during World War II, which involved everything from repairing damage sustained in battle to making alterations so they operated more effectively. Although their job was typically reduced to “keeping them flying,” it was much more complex.

Mechanics underwent three steps of training: basic, technical and unit. They would select a specialty, after which they’d undergo extensive training to become either a welder, metal worker or propeller specialist. Beginning in 1943, every American airman had to wear a special patch on their uniform to indicate what their technical specialty was.

In most cases, the crewmen would be transferred to a squadron once their training was complete, and they were able to focus on repairs and maintenance. They traveled with their units to their intended operational theater, which some were able to choose. Other mechanics were sent to work at depots or in mobile repair units.

Air Service Command

On a much larger scale than individual squadron mechanics, the Air Service Command, as it was known during World War II, played a major role in the repair of American aircraft operated by the US Army Air Forces. Essentially, its role was to manage the storage and distribution of supplies needed to repair and maintain aircraft operating in the many theaters of the conflict.

While its members operated out of the US, it was also responsible for controlling the many air depots outside of the country’s continental limits. Throughout the war, however, what the Air Service Command controlled fluctuated greatly, as officials realized it was better for an individual unit commander to have control over their resources.

The Air Service Command had many bases in the US, which were used for a variety of purposes, including the training of 5,000 men to repair aircraft as part of a top-secret project. This work was done out of its base at Brookley Army Air Field, Alabama.

Operation Ivory Soap

While most aircraft were maintained by standard ground crews, there were special fleets used in the Pacific Theater to keep them in the fight. Operation Ivory Soap was a classified project, which saw six Liberty ships converted into repair vessels.

These large vessels were specifically used to repair the B-29, as the aircraft was at the heart of the American forces’ island hopping strategy in the Pacific during World War II. These repair ships meant aircraft conducting long distance missions away from Allied airfields had somewhere to land for repairs, refueling and rearmament.

In addition to Liberty ships, there were also 18 Aircraft Maintenance Units used to repair smaller fighter aircraft, helicopters and amphibious vehicles on auxiliary aircraft repair ships. The first Aircraft Repair Unit was deployed in October 1944, with the remainder of the fleet sent into the field by February 1945.