Five hundred years before the start of World War I, the Teutonic Knights were gravely defeated by Slavic and Lithuanian forces at the Battle of Tannenberg (otherwise known as Grunwald). In 1914, the Germans practically slaughtered the entire Russian Second Army over the course of just four days, just miles away from the site of the 1410 battle. Given this, German officials couldn’t help but name the site their historic win, “Tannenberg.”

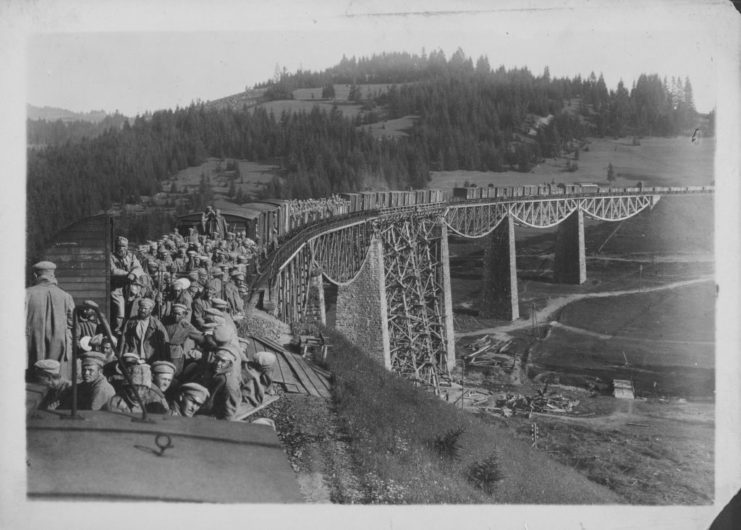

Early days of World War I

Germany entered the Great War following the Schlieffen Plan, influenced by Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his vision of a sweeping German invasion of France and Belgium. The plan was to gather the country’s allies, before moving toward France via the Netherlands, where they would defeat the French Third Republic. At the same time, a limited German contingent would travel toward Russia to fend off potential attacks, until the triumphant soldiers arrived to bolster their numbers.

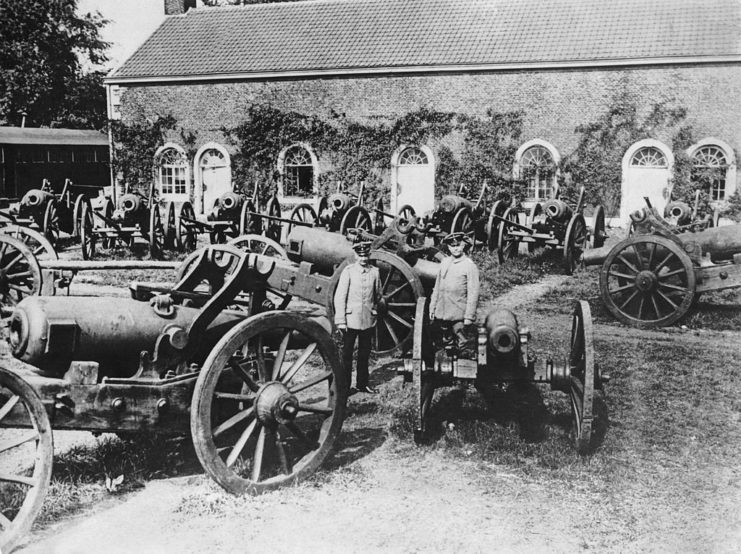

The entire strength of the German Army in 1914 totaled 1,191 battalions, the majority of which were deployed to France while the Eighth Army of East Prussia, comprised of just 10 percent of Germany’s entire military, set their sights on Russia.

Meanwhile, France organized a speedy mobilization of its forces, followed by an immediate attack to drive back the encroaching Germans. Buying time for the British and Russians to establish their defenses, neutral Belgium was defeated after two weeks of intense fighting during the Battle of Liège – the first official battle of WWI.

Battle of Gumbinnen

The Eighth Army was by far the most inexperienced company in the Imperial German military. It was comprised of reservists and garrison troops, and led by Generaloberst Maximilian von Prittwitz, who was surprised to find the Russians had mobilized much faster than he’d anticipated.

Was Russia doomed from the start?

The lead-up to the Battle of Tannenberg likely sealed Russia’s fate before the fighting even began. The Russian Army, with little experience, made a massive mistake when it came to its radio communications. Orders were being transmitted to personnel on open radio frequencies, and even though they were encoded, the Germans easily intercepted the messages and used them to their advantage.