Speaking from his office in D.C., Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg discussed the announcement with Outdoor Life. He touched on why wildlife crossings can be a vital addition to American infrastructure, and how the development of this new program has helped him see our road system in a new light.

“This is something that’s really new for the Department of Transportation,” Buttigieg says. “I did not realize coming into this job that I would spend nearly as much time as I have learning about anadromous fish, mountain lions, and elk migrations. But it’s something of deep human, economic, and safety importance, and it has great importance from a conservation perspective as well.”

How Crossings Can Save Human Lives and Benefit Wildlife

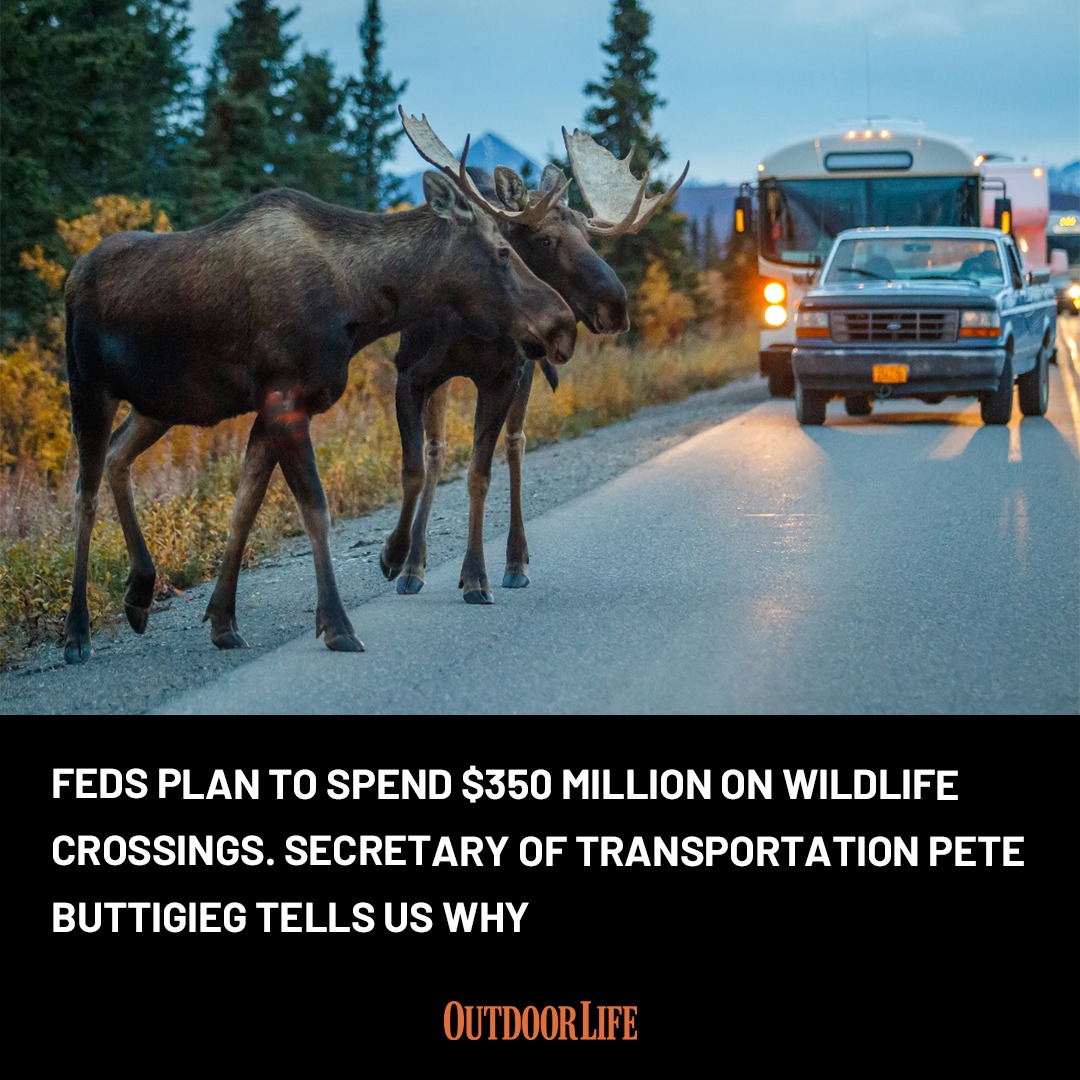

Even if you’ve never crashed into a deer or swerved to avoid a jackrabbit, chances are you know someone who has. This is especially true if you live outside a major metropolitan area.

A 2008 study by USDOT’s Federal Highway Administration found that, on average, there are more than one million vehicle collisions involving wildlife in the U.S. each year. These collisions cost the public more than $10 billion annually — primarily in the form of medical bills and damaged vehicles. The economic costs seem trivial, however, when compared to the roughly 200 fatalities and 26,000 injuries to drivers and passengers as a result. The critters on the other end of our bumpers fare worse: An estimated 2 million wild animals are killed by cars in America every year.

Our fates on the road are, in a sense, intertwined, as both humans and wildlife must travel to survive. When road workers paved the nation’s first stretch of asphalt in 1870, cars had only recently been invented. In the decades that followed, more gas-powered vehicles started showing up on America’s roads, but they didn’t travel fast enough to have much of an impact on wildlife. It wasn’t until the 1940’s that economy-class cars could maintain speeds above 60 mph. The term “roadkill” was coined roughly 20 years later.

“You look at our roads on a map, and it looks like a little ribbon. It seems like it couldn’t have that much of an impact,” Buttigieg says. “But it effectively cuts off one side from the other, whether you’re talking about [a deer] in an urban neighborhood or a predatory big cat that needs a large radius to hunt in.”

These effects are most prominent in areas where migratory species like mule deer and pronghorn antelope are present. Accordingly, Western states have begun to lead the way in re-engineering roadways to benefit wildlife. The Utah Dept. of Transportation built the country’s first wildlife bridge in 1975, and the state has constructed more than 50 additional crossings since then.

Other states like California and Washington have made similar strides in recent years. A 2022 study by Washington State University that focused on the 10-mile stretches surrounding these structures found that wildlife crossings in the state have already resulted “in one to three fewer wildlife-vehicle collisions on average per mile per year.”

How These Wildlife Projects Were Chosen

Looking at the 19 grant-funded projects that were just announced, many of the applicants were state transportation agencies that couldn’t otherwise fund such ambitious work. One $22-million grant will allow the Colorado DOT to build a dedicated wildlife overpass spanning six lanes on Interstate 25 between Denver and Colorado Springs. The burly bridge will benefit elk and the other migratory species that inhabit the transition zone between the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. It will also make driving north-to-south safer for the constant stream of motorists who travel between Colorado’s two most populous cities.

Similarly, an $8.6-million grant awarded to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes will fund the construction of an overpass spanning U.S. Highway 93 in Montana’s Ninepipe National Wildlife Management area. Although the highway receives far less traffic than I-25, it’s a stretch of road that’s notoriously deadly for grizzly bears.

Most of the big-ticket grants that were announced on Dec. 5 will fund projects in these and other Western states. This is because there are more migratory species criss-crossing the West, and modern GPS tracking has given biologists a better understanding of their migration patterns. Many of these animals are also bigger and deadlier. (Research shows that human fatalities are 13 times more likely when a car hits a moose versus a whitetail deer.)

The federal program isn’t strictly focused on the West, however, and eight of the wildlife-crossing projects moving forward are in the Midwest, South, and East. With a few exceptions, most of these projects are more based around research than road construction. One grant that was awarded to the Connecticut DOT, for example, will fund a statewide plan to identify critical habitat blocks and wildlife corridors used by whitetails, black bears, wild turkeys, and other animals.

Buttigieg says picking and choosing between the overwhelming number of project applications USDOT received was a challenge. He explains that their foremost consideration was weighing which projects would be most effective and save the most lives. They also leaned toward proposals that were well thought out and detailed in terms of maximizing federal dollars.

“There’s always more ideas and proposals than we can say yes to, but you know, we started at zero,” Buttigieg says. “This is not the only round, either. And those that didn’t make the cut but had a pretty compelling case — we encourage them to come back again next year.”

In August, USDOT launched a similar infrastructure program that benefits aquatic species by contributing $196 million toward repairing and replacing many of the outdated culverts that run underneath U.S. roads. When these critical structures are damaged or compromised, they can cause flooding and restrict fish passage—sometimes blocking it entirely.

Read Next: The Key to Solving Big-Game Migration Conflicts? Roadkill

Buttigieg sees the programs as two sides of the same coin, and he believes their successes will serve as further proof that America’s fish and wildlife are worth investing in.

“If you can eat into a problem that costs the public $10 billion a year with a tiny fraction of that in terms of investment, that’s a pretty good return,” he says. “So, even in a kind of cold, hard financial sense, I think these efforts are going to prove themselves.”