The US military has a long and complicated history when it comes to the treatment of minorities within its ranks. While things have certainly improved, it’s important to remember the struggles many faced while fighting for their country. This is especially true of African-Americans during the First World War.

War History Online was lucky enough to speak with US Lt. Gen. Larry R. Jordan about this and his own 35-year career within the US Army. His insight was invaluable and adds a lot of weight to what should be an ongoing conversation.

Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan’s education and entry into the US military

Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan was born on February 7, 1946, in Kansas City, Missouri. While attending Central High School, from which he graduated in 1964, he was a member of the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC), which was a mandatory requirement for males at the majority of Kansas City’s public high schools. JROTC sparked Jordan’s interest in the US military, as did studying history, and he made the decision to apply for the US Military Academy West Point.

According to Jordan, West Point provided him with the foundation needed to succeed in his career in the Army. After graduating in 1968 with a Bachelor’s Degree in engineering, he was commissioned into the Army as an armored officer, and later earned his Master’s Degree in history at Indiana University Bloomington. That wasn’t the end of his education, however, as he dedicated his time to learn a number of different disciplines.

While with the military, Jordan also attended the National War College at the National Defense University, the US Army Armor School, the US Marine Corps Amphibious Warfare School (now the Expeditionary Warfare School), the US Army Ranger and Airborne School, and the US Army Command and Staff College (CGSC). He also completed the National and International Security Management program at Harvard University in 1992.

“I learned a lot about myself [at West Point],” he shared. “I learned a lot about how people react to various situations and stresses. You learn that in a lot of schools – particularly Ranger School – you learn that about yourself. You learn how much you can endure and still function. You learn how people react when they’re tired, hungry, concerned, frightened, and how you have to attempt to lead them.”

Serving with the “Big Red One” in Vietnam

Throughout his 35 years of service within the US Armed Forces, Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan fought in a number of conflicts and was stationed in a number of countries. From 1969 to 1970, he served a combat tour in Vietnam with the 1st Infantry Division – the “Big Red One” – which is the oldest continuously serving division within the Regular Army. It was founded in May 1917 and is headquartered at Fort Riley, Kansas.

During the Vietnam War, he was assigned as a platoon leader, along with two others who attended West Point with him. In 1969, the US government had conducted draft lotteries and, as a result, many of those serving overseas hadn’t volunteered to serve and “wanted to get on with their jobs. They wanted to get past that and move on.”

Despite the many men who had been drafted, Jordan didn’t see a decrease in troop morale, and he himself knew his mission was to “go after the enemy, but at the same time bring Americans home alive and well.”

Vietnam was the first American-involved war where White and African-American troops weren’t segregated. While racism and informal segregation did occur in some combat units and even during the recruiting process, Jordan shared he himself didn’t experience any discrimination because of the color of his skin.

“I never faced any official discrimination,” he said. “The Army by that time had some pretty stringent rules against discrimination. They wanted to treat all soldiers equally because they wanted to keep morale up – if you want unit cohesion, you’ve got to have that. Of course, you run into individuals whose personal prejudices and biases just come to the surface, and if you confront those in a professional way…”

Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan’s service in Operation Desert Storm

Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan also served his country during Operation Desert Storm. He was fighting with an all-volunteer force, as opposed to the largely draft Army he’d fought alongside in Vietnam. As well, the Army was quite a bit more capable by 1991, “because we had made great progress in technology, our equipment – even our training methodologies were better.”

When asked to compare the difference between both Vietnam and Desert Storm, Jordan said it came down to his rank at the time and the different perspectives that came along with that.

“In Vietnam, I was there with about 35 soldiers and a platoon, and out there on the ground and moving through the bamboo or the jungle or the sawgrass,” he explained. “In Desert Storm, I was a major general and I was certainly in harm’s way, but I had different concerns and worries, and those concerns were, ‘Are we doing the right thing for our units? Are we going to get units in trouble? Can we supply them? Can we provide them with the support they need?’”

Additional service in the US Army and retirement

Outside of Vietnam and Operation Desert Storm, Larry Jordan served three different tours in Europe, including as the deputy commanding general of the US Army and the 7th Army in Germany. He also conducted three tours at the Pentagon, as well as assignments in Israel and the Middle East.

While on duty in the United States, he held many prominent positions, including the commanding general of the US Army Armor School, the Deputy Inspector General of the US Army, and the Inspector General of the US Army, the latter of which allowed him to work closely with the Secretary and Chief of Staff of the Army. On top of all this, he also served as an assistant professor at West Point for three years.

Jordan’s last assignment prior to his retirement was as the deputy commanding general of the US Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) headquarters at Fort Eustis, Virginia (now Joint Base Langley-Eustis) from 2001-03. At the time of his retirement from the Army, he’d left a legacy that included the Distinguished Service Medal, the Silver Star, the Legion of Merit, and the Bronze Star, among a number of other decorations.

Following his retirement, Jordan became the senior vice president of Burdeshaw Associates, a business consulting agency, and is currently the Principal of LNJ Group, LLC. He’s also a member of the Council of Trustees of the Association of the US Army, the Board of Directors of the National Urban Fellows and the Board of Directors of the Army Historical Foundation.

When asked what he’d like his legacy to be, he responded, “I tell folks that the only legacy that any of us can leave in the Army or any of the services is in terms of the people and places we touch. We touch them for the better or the worse. I hope I touched both for the better.”

African-Americans enlist to serve in World War I

For Memorial Day 2022, Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan is speaking at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, in recognition of its “Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow” exhibit. While he wants to recognize all Americans who served during World War I, he wants those in attendance to remember the causes for which they fought: “liberty, justice, freedom [and] democracy.”

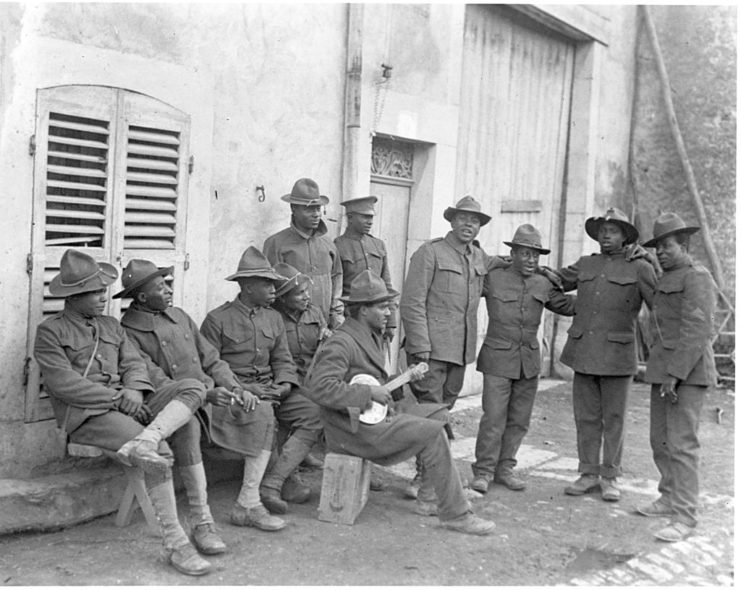

Before one can truly understand the depth of Jordan’s words, an understanding of the service of the nation’s African-American population must first be discussed. Over the course of WWI, around 200,000 African-Americans served the country, with 100,000 of those men being sent to Europe. Of that total, only 41,000 were assigned to combat roles. The rest were assigned to segregated labor battalions and made to perform menial tasks.

When the US officially joined the war in 1917, the country only had four all-Black regiments: the 24th and 25th infantry and the 9th and 10th cavalry. At that time, over 20,000 African-Americans enlisted with the military, a number which increased following the enacting of the Selective Service Act, which required all males between the ages of 21-31 to register for the draft.

Once enlisted, African-American trainees were subjected to the same racist and discriminatory behaviors as they had been while civilians; Jim Crow attitudes and laws had followed them into the military. Segregated transportation drove them to segregated military bases and training facilities. While protests occurred, little was done to rectify the situation, with the Department of War unwilling to “undertake at this time to settle the so-called race question.”

African-American units are deployed to Europe

African-American units provided much-needed support to America’s allies in Europe. The first units to arrive in France were laborers, engineers and stevedores, with the 369th Infantry Regiment, a combat regiment consisting of Black troops, arriving soon after. They were known by a number of nicknames, including the “Men of Bronze” and the “Black Rattlers.”

The 369th served the longest of any regiment in a foreign army during WWI, and they were the first to reach the Rhine River. They saw a lot of action during their 191-day deployment, including at the Second Battle of the Marne. They were treated equally by their White counterparts in the French Army, a stark contrast to how White American troops viewed them and their service.

The 370th Infantry Regiment, 93rd Infantry Division, nicknamed the “Black Devils” for the fierceness of their fighting force, was another African-American unit assigned to the French Army. What made the 370th so notable was that it was the only one commanded by Black officers. The regiment’s troops fought with distinction in both Belgium and France, participating in the Oise-Aisne Offensive, among other engagements.

Of note are the 104 African-American doctors who volunteered to serve in the country’s all-Black units. They began their training in August 1917, learning about medical and sanitation procedures in combat zones. While 118 doctors attended this training at the segregated Medical Officers Training Camp at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, only 104 graduated. They left for France in May 1918.

Attitudes didn’t change after the armistice

By the time the armistice with Germany was signed on November 11, 1918, African-Americans had served in a number of units and roles. They’d used the war to show their patriotism and that they could contribute to the defense of the country, something that was encouraged by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Upon their return home, Black servicemen expected greater equality. What they faced, however, was more persecution. Talk of the contributions African-Americans had made to the war effort was deemed to be lies, and many veterans were threatened with death if they went out in public in their military uniforms.

Many were physically attacked during a number of race riots that broke out in the middle of 1919. Dubbed the “Red Summer” by author and civil rights leader James Weldon Johnson, these violent clashes broke out in a number of American cities, including Chicago, Virginia, and Washington, DC.

Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan’s thoughts on how African-Americans were treated

Following WWI, America’s Black population continued to suffer under racist ideologies. While he hates to speculate, Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan feels the country may have moved away from such activity had different policies been in place, in regard to military service. He also feels the same can be said about state and community laws.

He also adds that the treatment of African-Americans created resolve within the community, saying, “There was disappointment, but there was also resolve, and I tell folks that out of that experience grew what was to become what I call the ‘Double V’ campaign – World War II. A lot of African-Americans said, ‘We have two things – victories – to achieve: victory overseas and victory at home.’

“That energized part of the early Civil Rights Movement and, of course, I think it was July 26th of ’48 [that] President Truman signed the executive order desegregating the Armed Forces, and from then on there’s been steady progress. In many ways, I think the Armed Forces – the Army, in particular – has led the way in that. Not only for African-Americans and other minorities but for women and others.

How is equality presented in the US military today?

When asked what the Armed Forces can do to continue to promote equality within its ranks, Lt. Gen. Larry Jordan looks back on his own experiences. As the Inspector General of the Army, he “got a chance to look at the good, the bad, the ugly, and, quite frankly, of all the things I saw, about 95 percent were great. People doing the right things – trying to do the right things.” That’s not to say, however, that people didn’t sometimes “stumble and fall.”

He feels the military is doing the right things and making steps in the right direction but adds that the services need to continue to stress the importance of servicemen and commanders doing what they’re supposed to, which can sometimes be hard, given all they have to contend with.

“The problem is all services have a lot on their plate,” he explained, “and I’ve seen a number of times when the Army will solve a problem and it’ll put it aside and say, ‘Solved that problem. Let’s move to the next challenge.’ And left by itself, because all of the services are made of humans, imperfect humans, those things can get out of order, they can go awry if you don’t keep your eye on them. So you occasionally have things that flare-up.”

To conclude, Jordan spoke about the progress the Army has made since he enlisted in the 1960s.