On May 6, 1937, the 30-year era of rigid airships came to a sudden, shocking end. The massive, lighter-than-air civilian aircraft known as zeppelins had been the last word in luxury transport for more than a decade, crossing the Atlantic in near silence and bringing Europe and the United States within easy aerial reach for the first time.

But, on that fateful day, it all came crashing down. The mighty Hindenburg, pride of the Nazi regime and wonder of the age, burst into flame as it came in to land at the Naval Air Station Lakehurst, near Manchester Township in New Jersey.

Airships when grounded were tethered to a mooring tower, the most famous of which sits atop the Empire State Building (although passengers were understandably queasy about disembarking there). As the airship came in to its mooring tower, in an instant it caught fire and crashed to the ground. The whole incident took fewer than 40 seconds.

The disaster took 35 lives on that airship, and one ground crew member was also killed, but amazingly 62 out of the 97 passengers and crew did survive this accident. The entire event was sensationalized when reporters and film crews captured the explosion and crash from the ground, with Herbert Morrison recording the famous words “Oh! The Humanity!” as the flaming wreckage came down in front of his eyes

The End of the Zeppelin Era

Thirty years of passenger travel with the commercial zeppelins came to an end on that day. By the time the Hindenburg came in to land, there had been around 2,000 operational flights without a single injury being recorded.

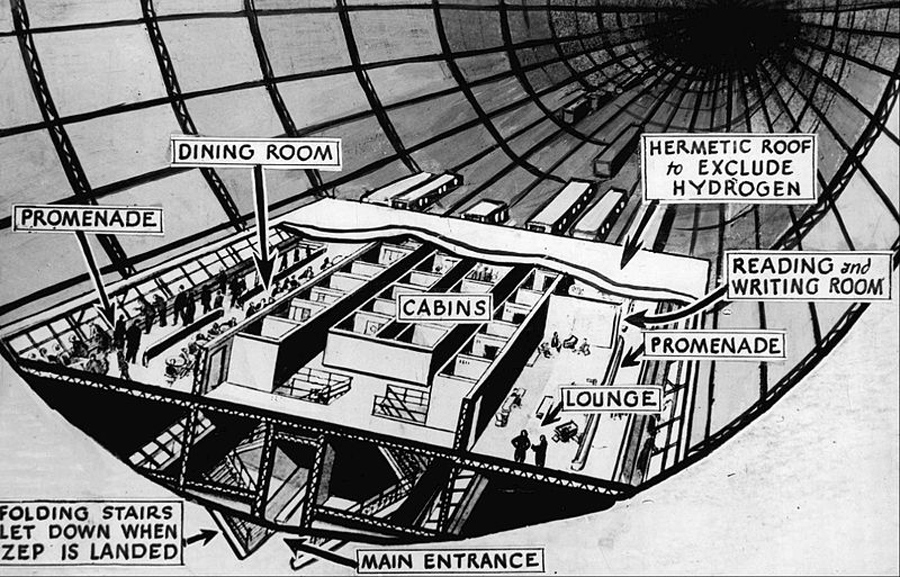

Furthermore, zeppelins were the last word in luxury travel. Passengers onboard the Hindenburg were able to travel from Europe to North and South America in just half the time that the fastest ocean liner took. Moreover, the interiors were also more luxurious than any aircraft before or since, spacious and comfortable. There were dining rooms, a piano lounge, comfortable sleeping cabins and even a smoking room nestled between the vast hydrogen cells that kept the airship afloat.

But was it the hydrogen, the very gas which allowed the Hindenburg to float in the sky, also the cause of the disaster? After all, 7 million cubic feet (200,000 cubic meters) of highly flammable hydrogen gas was stored right above the passenger quarters.

Inherently Flammable

And, after around 80 years of scientific and research tests, this is one of the preferred conclusions for the cause of the explosion. Many believe that the Hindenburg disaster occurred due to an electrostatic discharge or spark, which then ignited hydrogen which was leaking from one of the cells.

Conditions were not unmanageable that day, but there was a thunderstorm in the area and the pilots of the Hindenburg noted a strong, gusting crosswind as they came in to land. Although there was only a light rain, it was also noted that a strong static force had built up in the air, capable of creating a spark at any moment.

When the accident took place, the airship was only 200 feet (60 meters) above the ground of the airfield. The atmosphere was electrically charged, but the metal framework of the zeppelin was grounded with the landing line.

The difference in this electric potential may well have caused a spark to jump off the fabric covering of the ship to the framework of the ship, which was grounded to the landing line. The fabric covering was supposed to prevent any dangerous sparks from reaching the interior structure, but somehow this still happened.

Answers to the Wrong Questions

That the Hindenburg disaster was due to the hydrogen igniting is hardly surprising, however. The fact that hydrogen was highly flammable was well known to the designers and operators of airships, and safety procedures were in place to ensure it could not catch fire.

So the issue with the Hindenburg fire is much more about how the hydrogen could ignite, the first such occurrence in 30 years. And here there are various theories as to the cause, and the original site of the fire which ignited the gas.

Many believe that there was some kind of hydrogen leak caused by the gusting wind in the moments before the crash. This is supported by later testimony from eyewitnesses on the ground, who reported seeing fluttering fabric panels towards the rear of the Hindenburg, just forward of the rear vertical fin.

The fabric should have been taut and it seemed the fluttering could only have been caused by a tear in the surface layer of the ship. This could have allowed hydrogen to escape, and also potentially exposed the metal framework of the ship to a static discharge.

So, is that it? A hole in the Hindenburg allowed hydrogen to escape, and then a spark from the metal framework ignited the leak? Sadly, this does not offer a full explanation and there are other competing theories which merit consideration.

A Poor Choice of Fabric

The Hindenburg’s distinct and beautiful silver color was due to the use of aluminum powder in the fabric covering the ship. This strengthened the fabric and protected it from ultraviolet deterioration, and the impact of water, wind and other small objects.

But aluminum powder is a dangerous and potentially highly flammable substance, every bit as risky as hydrogen under the wrong circumstances. In fact, it is even used as a component of rocket fuel, albeit in a much different configuration to its use on the Hindenburg.

It may seem an unimportant distinction, but in reality these two different causes have massive implications for rigid airships. These may even come to be relevant if, in the future, such designs are ever revived.

If a spark on the exposed framework ignited hydrogen gas then the problem was one of structural strength. Design improvements should consider strengthening the skin of the aircraft and the hydrogen cells within, as without the hydrogen leak the aircraft would have landed safely.

However, if a spark was able to ignite the fabric itself then the problem is with the material used in her construction. If another, more safely inert material were to be used the fire could not have started, and crucially this suggests the structural design of the Hindenburg herself was not at fault: She was strong enough to survive that day.

The Last Flight of the Hindenburg

Over the years, other, more outlandish theories have been suggested. Could the Hindenburg have been struck by lightning, or destroyed due to sabotage within or without?

None of the other theories are really plausible, however. The camera footage of the accident and statements from the witnesses on the ground do not show evidence of any lightning strike, and it is clear that the fire starts on the upwards rear surface of the zepellin, and not from some internal explosion.

In the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, there is a small chunk of the internal-support girder of Hindenburg aircraft. People still mourn for the lives lost that day, and the world lost one of its great innovations in transport, gone in seconds and in flames.

Top Image: The Hindenburg bursts into flame. Source: Arthur Cofod Jr / Public Domain.