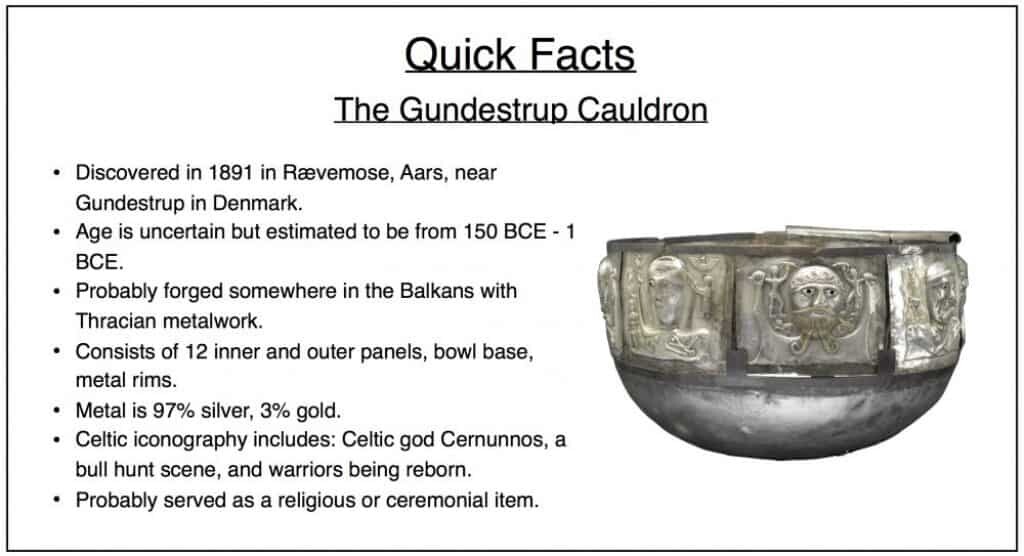

About 2000 years ago, someone in Rævemose near Gundestrup, Denmark, carefully buried a stack of silver panels tucked into a semi-circular silver bowl. Each of the panels revealed exquisite scenes of Celtic mythology and religion consisting of animals, heroes, and gods, and they were superb examples of highly crafted metalwork. On May 28, 1891, a peat collector working in the bogs unearthed the silver panels. Archaeologists studied the pieces and realized that when fully assembled with the bowl, they formed a large vessel. This historical and mysterious treasure is the Gundestrup cauldron.

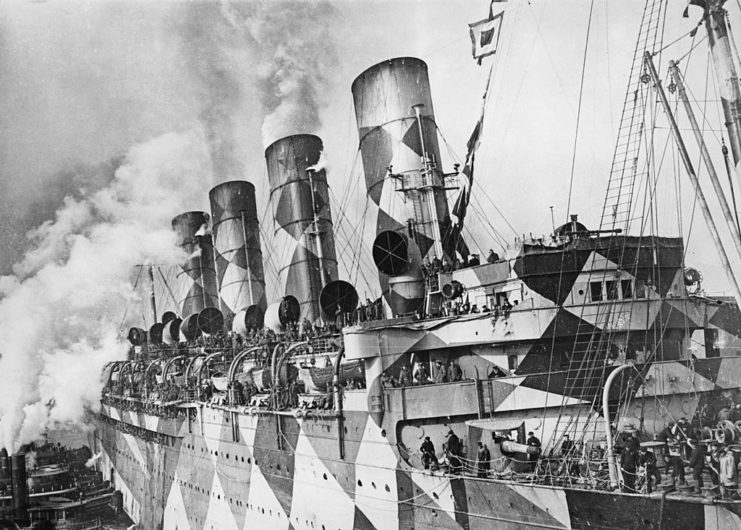

The Gundestrup cauldron is located at the National Museum of Denmark. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Nationalmuseet.

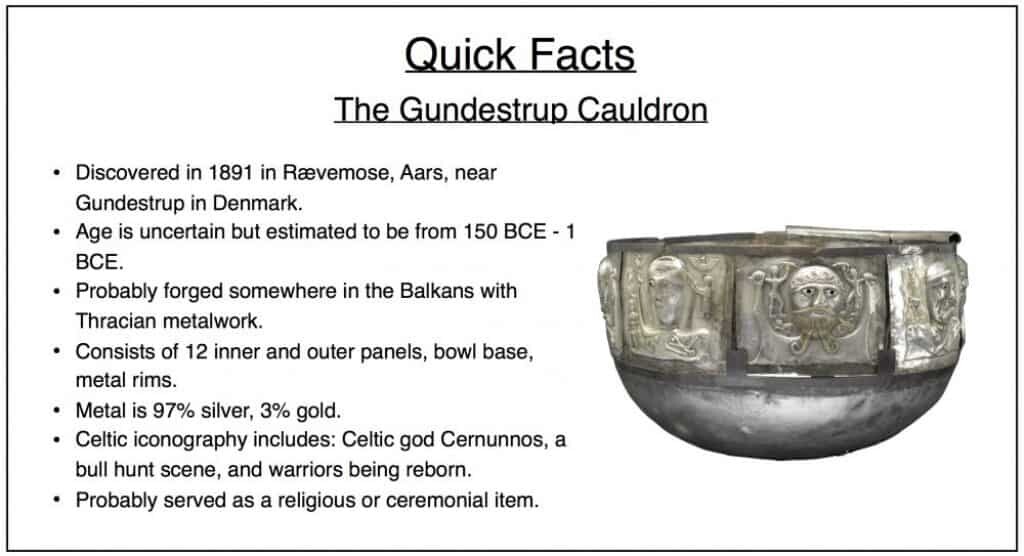

Sophus Müller, a Danish archaeologist, reassembled the cauldron after the discovery. Five of the panels are larger rectangles and seven are smaller and more squarish. There were originally eight smaller panels, but one was missing since the discovery. The large semi-spherical bowl is the base of the cauldron. The seven cauldron panels form the outside of the vessel while the five larger panels face inward. Separate silver rims connect the pieces together. Müller sent the metal for analysis, and the results indicated 97% silver and 3% gold. The Gundestrup cauldron fully assembled is 27 inches in diameter and 16-1/2 inches tall. It weighs nearly 20 pounds.

For many years scholars believed the vessel originated from Celtic Gaul, however, upon further examination they reformed their opinions. It seems the spectacular vessel it is not just Celtic after all, but an intermingling of different cultures.

Where Was the Gundestrup Cauldron Made?

The history of the Gundestrup cauldron dates back to between 150 BCE and the birth of Christ. Today, most experts believe that the Celtic cauldron was forged in the Balkans with Thracian metalworking. But clearly, someone who was possibly of Celtic origin and well-versed in Celtic religion took great care to ensure that many significant religious icons were displayed on the vessel.

Celtic Expansion in the East

By tracing the movements of the Celts, we may be able to glean some information about the potential history of the Gundestrup cauldron. Trade and migrations had been taking place across vast distances between the east and west well before the creation of the cauldron. During the “great Celtic migration” in 279 BCE, the Celts from the west invaded the Balkans, which included Thrace (Bulgaria and parts of Turkey and Greece). From there they moved into Anatolia (Turkey). They established themselves in upper Anatolia, which the locals would call Galatia. Those Celts became known as the Galatians (Gauls). Celtic presence in Galatia was long-lived, and because the Galatians were adept warriors, many regional forces hired Celts to fight battles in the Thracian region and into West Asia Minor.

The Roman Republic became the Roman Empire in 27 BCE and the empire was expanding. In 64 BCE Galatia became a Roman state. Subsequently, the Romans conferred the title of “King of the Galatians” to the Celtic leader, Deiotarius. The name Deiotarius means “divine bull,” and the significance of this is explained later. The area around the Balkans was very multi-ethnic, and at that time, the Thracians and the Scythians (North and Eastern Black Sea) had some of the finest metalwork.

Lughnasadh: The Celtic Pagan Harvest Festival

Thus, the cauldron may have been commissioned by a Celt who at one time lived or fought in the Balkan/Anatolian region. How the vessel made its way to Gundestrup, Denmark, is a mystery.

Important Symbols on the Cauldron

Central Bowl Bull

Without question, the most interesting facet of the Gundestrup cauldron is the numerous images that embellish its surface. There are symbols of fertility and destruction, life and death, and beauty. Most prominent of these is a medallion-like depiction of a bull hunt. This metallurgical piece of art forms the base plate of the cauldron. Additionally, experts believe that golden horns were once attached to the bull’s head. The bull motif is also accompanied by three dogs. One of the dogs seems to be hurt or killed; it is curled up at the rear of the bull and appears less prominent. In contrast, the other two dogs appear to be hunting the bull. Above the bull, a female warrior is leaping into the air with a raised sword ready to strike the powerful beast.

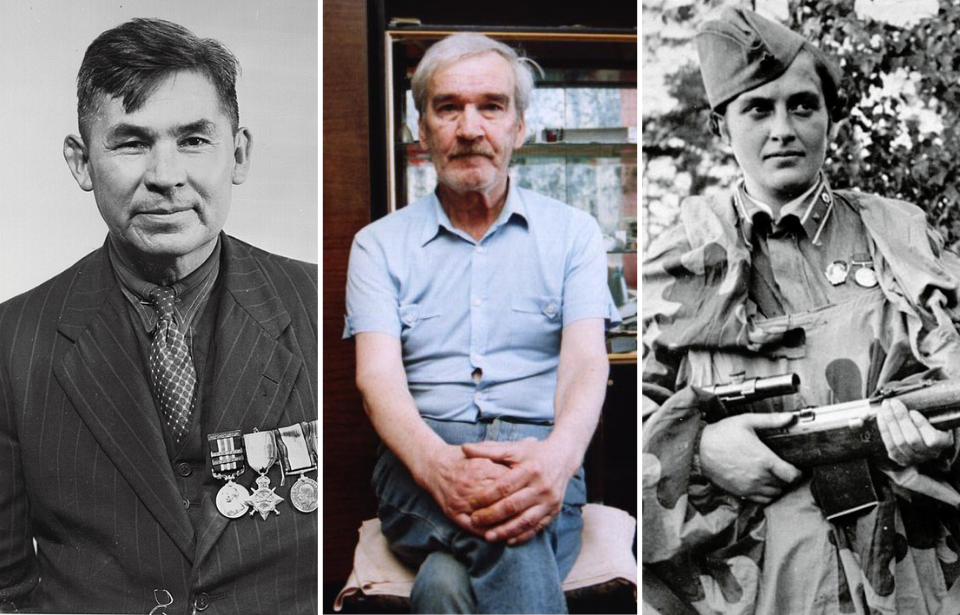

Center medallion of bull hunting scene at the bottom of the cauldron. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Claude Valette CC.

Since antiquity, the bull possessed very strong magical symbolism to the Celts. It represented power, strength, and virility. Bull sacrifices were common, and there is an early Irish story, Táin Bó Cúailnge or Cattle Raid of Cooley, which involved two supernatural bulls. The golden horns of the bull in the cauldron were also significant.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Miranda Green”]Bull horns were a highly potent symbol adopted from anthropomorphic deities, the horns on the animal itself having attracted reverence from great antiquity.[/blockquote]

Now in reference to the Celtic king of Galatia, noted above. His name, Deiotarus or “divine bull,” reflected the deep respect and perhaps reverence that his people felt for him.

Warriors and the Dipping Cauldron

On another plate, two rows of warriors on horses are wearing clothing that is not of Celtic origin. The round discs on the horses’ straps are of Eastern European origin. However, on the same plate in the right bottom are men playing the carnyx (musical instruments), which are certainly of Celtic origin. A giant figure appears to be dipping one of the soldiers into what experts theorize is a cauldron of rebirth. This supports the belief that when one dies, he can be reborn into an afterlife. Some scholars also relate this with the Dagda, a great king of the magical tribe of mythological gods, Tuatha Dé Danann. The Dagda possessed a powerfully divine cauldron that never ran dry of food, it always satiated its user, healed the sick, and could even bring the dead back to life.

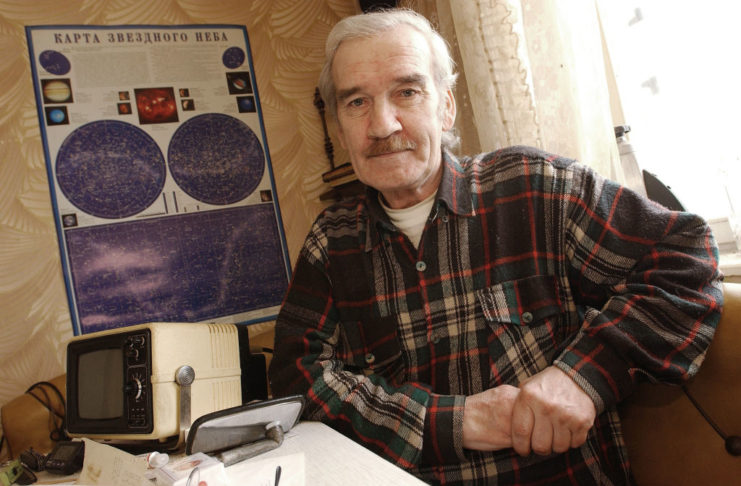

Scene possibly depicting the living and the dead and a resurrection by a god, 2012. Source: Wikipedia Commons, Claude Valette.

Cernunnos the Celtic God

It is the cauldron’s depiction of Cernunnos that firmly establishes the importance of the Celtic god. Often referred to as The Horned God, Cernunnos is depicted on one of the cauldron’s inner plates. He sits regally in a seated position and is surrounded by numerous animals such as a stag, canines, bovines, and even a dolphin with a human rider. The general impression is that Cernunnos serves a role of overseer.

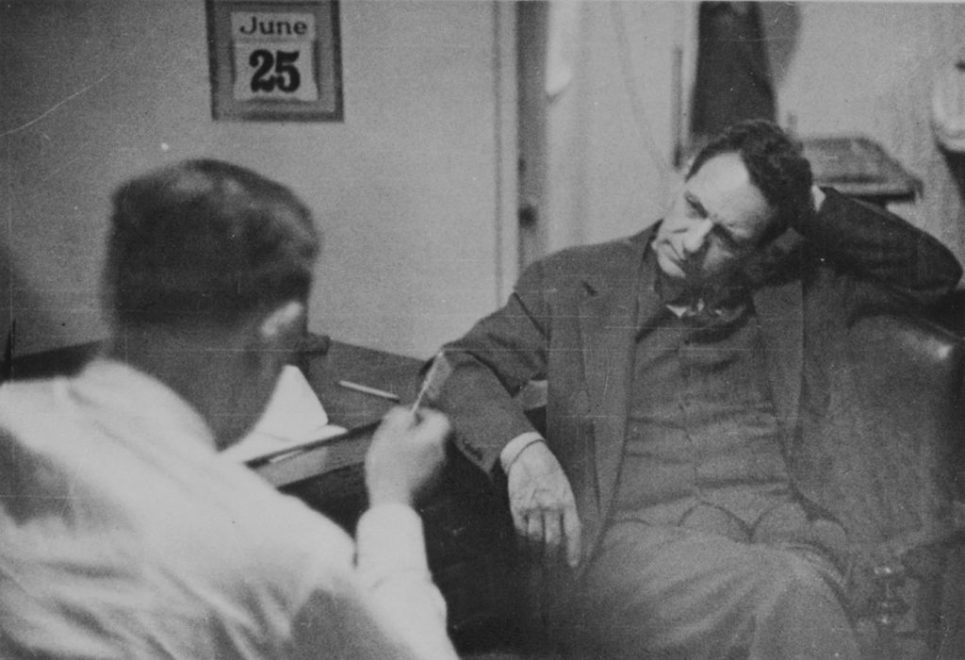

Celtic god Cernunnos holding a torc in one hand and ram-horned snake in the other. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Malene Thyssen CC.

Archaeologists have long known that Cernunnos was an important part of the Celtic pantheon of gods. There is evidence to suggest, however, that Cernunnos, like Zeus, Jupiter, and Odin, was the predominant god figure of the Celts. His consort was the Green Lady goddess. Together, they reigned over everything from hunting to planting.

What comes round again and again in the multitude of designs are hunting scenes, gods, and female warriors that could represent goddesses. This type of iconography is not unique to the Celts.

Similar Art in Other Cultures

Archaeologists have noted many similarities between ancient Anatolian art and the images which adorn the cauldron found in Gundestrup. Chief among these are scenes which appear to tell a mythological story. Archaeologists found similar bas-reliefs and engravings on 36 rock tombs of ancient Lycia. Images of funerary feasts, banquets, hunting, and battle scenes are present in these tombs which date to the 4th century BCE.

A silver Thracian plate from another grave found in Stara Zagora, Bulgaria also shows incredible similarities to the Gundestrup cauldron. The metal-work, the griffins, the stripes on the clothing of a man believed to be Hercules, and the postures of the fantastic animals reflect those of the caldron.

Furthermore, experts generally agree that Western European Celts did not yet possess the craftsmanship to construct such a complex piece.

Magic of the Silver Cauldron

Is it possible that the cauldron served some magic ritual or religious celebration? The Celts, like other ancient peoples, connected their daily lives to their gods, nature, and magic. Scientists discovered a substance on the inside of the cauldron. After a chemical analysis, it turned out to be beeswax (Nielsen et al.: 5). In ancient days people often used wax as a waterproofing agent. This may indicate that some kind of liquid was put into the cauldron. What the liquid was is pure speculation.

Additionally, archaeological discoveries and the efforts of researchers like Sir James Frazer has established the practice of magical ritual by the Celts. The noted anthropologist explored this notion in his seminal work, The Golden Bough. In the book, Frazer writes, “Religion consists of two elements, a theoretical and a practical, namely, a belief in powers higher than man and an attempt to propitiate or please them.”

It could be that the Gundestrup cauldron is an example of both. The presence of the Cernunnos figure and goddess iconography support the importance of religion to the Celts. They believed in hierarchical figures who played a role in the life of mankind.

Theories About the Cauldron in the Bog

To Appease the Gods

Did someone make the silver cauldron as a propitiation or sacrifice to the gods and goddesses of the Celts? Possibly. During the Celtic Iron Age and roughly the first two centuries CE, Celtic sacrifices of goods, foods, animals, and even people into the bogs were common. Some ancient people of Denmark believed that gods lived in the bogs. This was because the natural peatlands provided many blessings that were critical for their survival. Peat provided fuel for fires that warmed their longhouses. The makers of linen textiles soaked their flax and hops in the bog water for the retting process. Additionally, iron smelters collected iron ore from the bogs. As a result of their many resources, the bogs evoked great reverence and appreciation.

Peat collectors have found around 400 bog sites in Denmark with items buried in holes that people had dug into the peat. Many clay pots contained food, and nearby, the bones of animals and sometimes humans often lie in the bog. There were even discoveries of wooden plows, ships, many wheels, and carriage parts. It may be that the people wanted to give back to the gods of the bogs as much as the bogs provided for them.

To Provision One’s Afterlife

Ancient people of Denmark believed that after death they had to take a long journey to get to their afterlife. They typically cremated their dead on a funeral pyre. After the funeral, they placed the ashes into an urn and buried them – often along with some possessions and food for the journey to the afterlife. Therefore, goods in the bogs may have been both sacrifices and items that would accompany the dead on their journey. Perhaps after the owner of the Gundestrup cauldron died, the magical silver piece went into the bog to go to his or her afterlife.

Ultimately, we may never know exactly what the purpose of the Gundestrup cauldron was. We may never discover why someone had carefully buried it in the peat bog. It certainly meant enough to someone to transport it or have someone transport it to Denmark from a very faraway place, probably the Balkans. Perhaps it also meant enough for that person to take it to the grave and into the afterlife.