Hussars originated in Central Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries and were made up of light cavalry soldiers. Though military in nature, they can easily be compared to a European version of the American cowboy. Legendary German Field Marshal August von Mackensen was dubbed “The Last Hussar” during his service, which included commanding units throughout the First World War, despite being in his 60s.

August von Mackensen’s upbringing

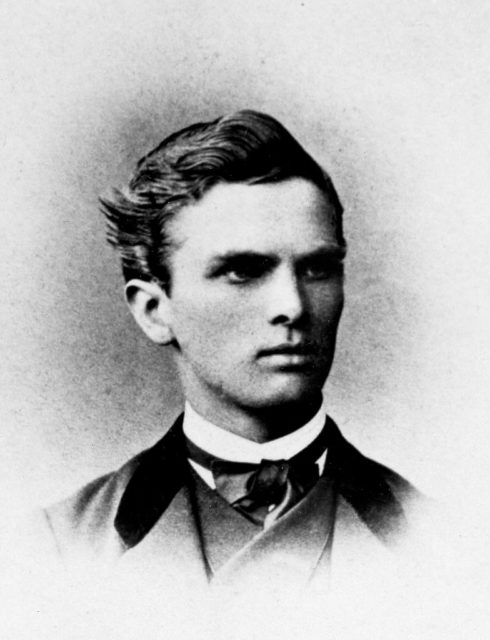

August von Mackensen was born in Haus Leipnitz, in the Prussian Province of Saxony, in 1849. At 20 years old, he volunteered to serve with the Prussian 2nd Life Hussars Regiment, seeing action during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. While participating in the conflict, he led a charge while on a reconnaissance patrol north of Orléans, which saw him awarded the Iron Cross Second Class and promoted to the rank of second lieutenant.

Following the war, von Mackensen attended the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg. However, he found himself drawn back to service with the Imperial German Army and rejoined his old regiment in 1873.

Continued success with the Imperial German Army

In 1879, August von Mackensen married Dorthea “Doris” von Horn. She was the sister of a slain comrade, and her father, Karl von Horn, was one of the most powerful and influential administrative officials in East Prussia. In addition to his happy marriage, von Mackensen found a key mentor in Minister of War Julius von Verdy du Vernois. His star quickly rose, and in 1891 he was appointed to the General Staff, despite not having the required experience.

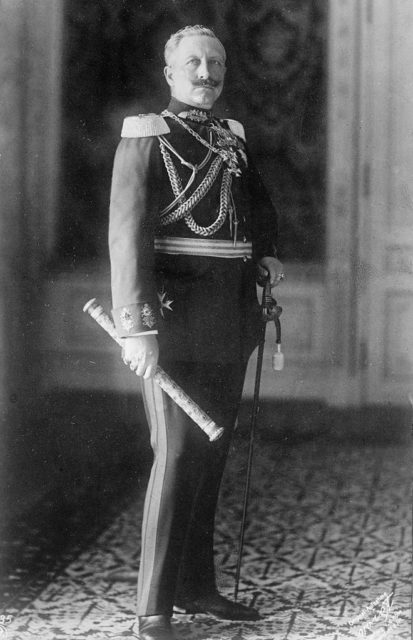

Kaiser Wilhelm II was also impressed with von Mackensen. In 1893, the German emperor gave him command of the 1st Life Hussars Regiment, and later made von Mackensen his adjutant. This was an exceptional honor, as he was the first commoner to serve in the role. He performed this duty for three and a half years, during which he met high-ranking officials across Germany and the world.

August von Mackensen’s service during World War I

When the First World War broke out in July 1914, August von Mackensen was 65 years old and still in charge of the XVII Army Corps. He was also one of the most experienced commanders in the Imperial German Army. Right off the bat, he led his men in a number of offensives, including the battles of Tannenberg and Gumbinnen. That September, he took charge during the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes.

In August 1915, von Mackensen commanded his men during the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive, one of the Central Powers’ most important victories of the war. After continued fighting against the Russians on the Eastern Front, von Mackensen participated in the Serbian Campaign, before going on to oversee the Romanian Campaign. Before long, he was known for being one of the world’s foremost military tactician.

Remaining out of the public eye during the interwar period

Following the signing of the armistice, August von Mackensen was arrested by the Allies for being a war criminal and held until November 1919. The following year, he retired from the Imperial German Army and opted to remain out of the public eye, as he disagreed with the establishment of the new parliamentary system and the restrictions placed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles.

Following the war, Germany was in shambles, and there were differing opinions on how to best move forward. In 1924, von Mackensen decided to use his status as a war hero to support both the monarchy and nationalist groups, frequently appearing in his Life Hussars uniform.

August von Mackensen’s legacy

August von Mackensen supported Paul von Hindenburg during the 1932 German election. However, when the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party came into power, he didn’t directly oppose the regime, later becoming one of its most visible supporters. That being said, the public were never really sure where he stood, as his actions brought about mixed messages.