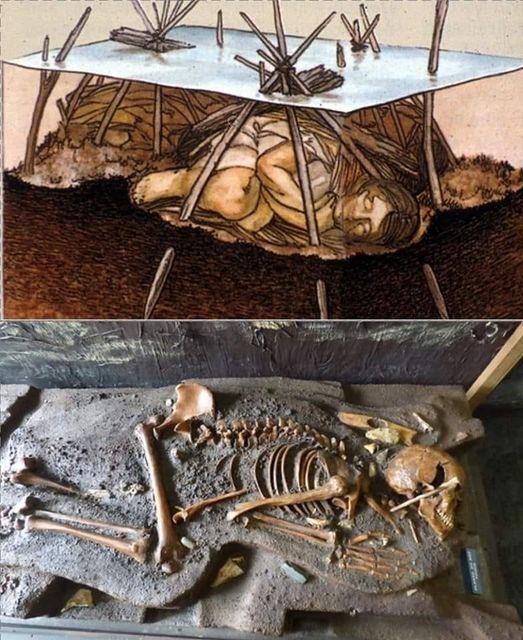

There is a fascinating ancient underwater cemetery in Florida, North America. It is called Windover Pond, and it is 8,000-year-old. Windover Pond is older than the Great Pyramids of Egypt and can help unravel the mystery of ancient Americans. The human remains discovered in the Windover Pond can even rewrite America’s ancient history.

There are many bog bodies in European peats, but they are not as well-preserved as the Windover bog bodies. There must have been some elements in the Windover sinkhole that helped protect the brain tissues for thousands of years.

Scientists suggest “that the slight acidity and high mineral content of the water in the sinkhole might contribute to their longevity. The preservation of brain tissues is reflected by preservation of ancient DNA, and the Windover sinkhole has yielded one of North America’s large ancient genetic populations.”

Some years ago, Andrew Merriwether, a geneticist of the University of Michigan, did one of the most extensive surveys of mtDNA sequences from modern and ancient native Americans.

When Hauswirth extended his DNA study, “one particular element caught his attention.

At one specific locus, all except one of the individuals shared one allele in common. In many a less variable region this would not merit comment, but in this highly variable part of the genome, it did suggest a blood connection between the individuals.

Among the Windover individuals, however, two particular microsatellite lengths dominate the population, one of nine repeats and the other of fifteen repeats. Alongside the HLA evidence this was further indication of close blood ties within a population placing its dead in the pond over several centuries.”

The fact that these people were related explains why they buried their dead in the Windover Pond.

The assumption about people who lived 8,000 years ago has been that they were too nomadic to develop much of a culture and certainly couldn’t afford to care for disabled people. Still, the Windover bog bodies tell a different story.

Among the skeletons found in the Windover sinkhole archaeologists found remains “of a boy crippled from spina bifida who had to be carried around and treated for the 16 years of his life. And there was an elderly woman who also needed such long-term care. Our ancient ancestors apparently tended carefully to each other despite their constant need to keep themselves safe and alive.”

What is still unknown is where these people originally came from, and there are some theories. The DNA studies indicate these people were of Asian origin, similar to the four other major haplotypes of Native American peoples.

“Merriwether believes the first Americans came from a single population in Asia, probably in a single wave, though the wave may have lasted for some thousands of years.” According to Merriwether there is no way to tell how long the doors was open, but it is possible to “imagine it as anywhere from one big migration with lots of people to a sort of continuous migration over a long period of time.”

Merriwether explained that genetic evidence does not tell when these people arrived.

The historical and archaeological significance of Windover Pond should not be underestimated. This site has provided “unprecedented and dramatic” information about early Archaic people in Florida and could be one of the most significant archaeological sites ever excavated in North America.