The KAI T-50 Golden Eagle is one of few supersonic trainers in the world and the first developed for the Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF). Further variants have been designed to transform this premiere trainer into a light-strike aircraft, with it seeing operational success in the likes of the Philippines. Over 200 T-50s have been produced and delivered around the world, and the aircraft has recorded well over 300,000 flight hours.

Development of the KAI T-50 Golden Eagle

Korean Aerospace Industries (KAI) collaborated with Lockheed Martin to develop the advanced trainer known the T-50 Golden Eagle. Following its development, the aircraft was intended to replace any aged models still active with the ROKAF, such as the Northrop T-38 Talon and Cessna A-37 Dragonfly.

The program to develop the aircraft was originally codenamed “KTX-2.” After some financial issues and a temporary suspension, the T-50’s first design was completed in 1999. The funding needed to manufacture the aircraft was then divided, with KAI taking on 17 percent, Lockheed Martin funding 13 percent and the remainder being supplemented by the South Korean government.

Based on the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon

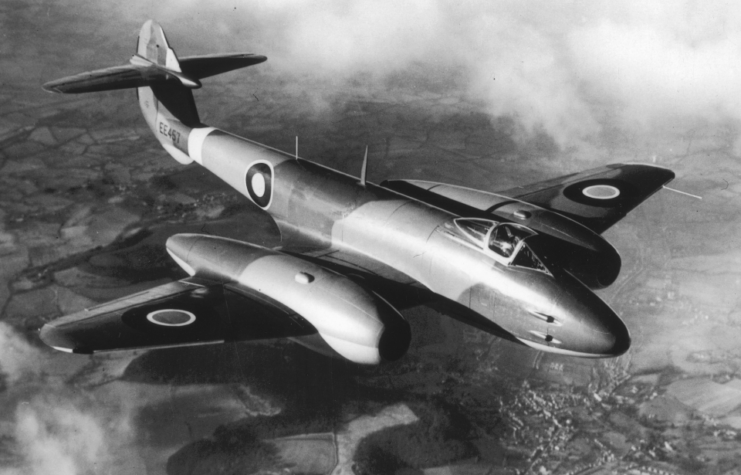

The KAI T-50 Golden Eagle strikes a remarkable resemblance to the Lockheed Martin F-16 Fighting Falcon. This is likely because the company makes a licensed version of the American aircraft, designated the KF-16. However, the T-50 is smaller than the F-16, making up only 80 percent of the latter’s overall size.

The T-50 is a tandem, two-seater aircraft with a large glass canopy for clear visibility. This feature also offers protection, as it can withstand impact against four-pound objects striking at 400 knots. The T-50 also has a single vertical tail fin and is powered by a single General Electric F404-102 turbofan engine, capable of 78.7 kN of thrust.

‘Fighter lead-in’

The TA-50 variant of the KAI T-50 Golden Eagle is considered a “fighter lead-in” version of the original supersonic jet. It serves as the in-between variant of three, offering deployment as both a fighter trainer and a light-attack aircraft. As such, the TA-50 can be armed, unlike its predecessor.

The TA-50 uses Elta EL/M-2032 advanced fire-control radar, and is designed to wield a variety of weaponry, including precision-guided weapons, air-to-surface missiles (Hydra 70, AGM-65 Maverick) and air-to-air missiles. It can also be fitted with the three-barrel version of the M61 Vulcan, firing 20 mm link-less ammunition.

Light-strike capabilities

The most advanced variant of the KAI T-50 Golden Eagle is the FA-50, which took its maiden flight in 2011. It has light-strike capabilities, and is designed to perform both day and night operations. Like the TA-50, the FA-50 is equipped with the EL/M-2032 fire-control radar, but has a greater range than the lead-in aircraft.

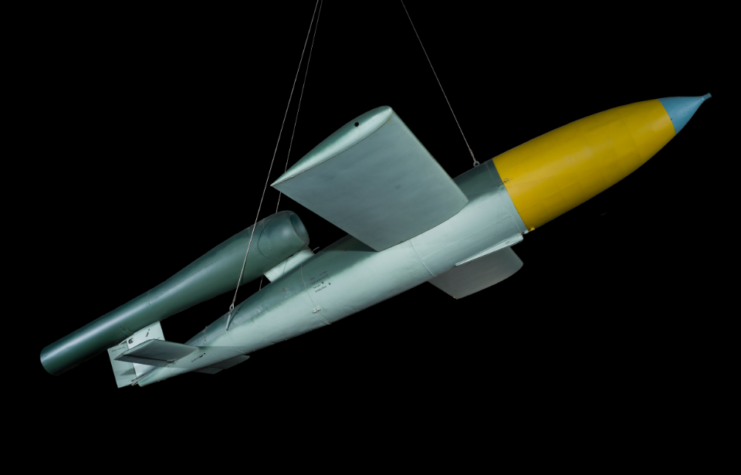

The FA-50 features a number of other enhancements that make it an outstanding light-combat jet. It has a higher internal fuel capacity and better avionics, and it can employ a large number of underwing ordnance. This includes air-to-air missiles, air-to-surface missiles, cluster bombs, general-use drop bombs, precision-guided bombs and unguided rocket pods.

Conducting missions in the Philippines

The KAI T-50 Golden Eagle and its variants are operated by a number of different nations, including South Korea, Iraq, Indonesia and Thailand. However, it’s the Philippine Air Force (PAF) that’s utilized the FA-50 in a wide array of air missions, showcasing its capabilities as both a lead-in trainer and a light-combat jet.

The PAF acquired 12 FA-50s, and it wasn’t long before they were participating in missions. On the night of January 26, 2017, two attacked terrorist hideouts in Butif, Lanao del Sur, Mindanao, marking the first combat flight ever conducted by the aircraft.

In June 2017, multiple FA-50PHs conducted airstrikes on the city of Marawi, after it had been overtaken by Maute terrorists. The following month, one was responsible for the accidental deaths of two Philippine soldiers after its bomb landed off-target. Several others were injured.