Several unusual aircraft have been developed over the years (just look at the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin), but few were as unique in appearance as the Northrop Tacit Blue. The technology demonstrator was designed to show that low-observable stealth aircraft could conduct surveillance operations deep behind (or over) enemy lines, without being detected by radar.

As with other surveillance aircraft developed by the US Air Force, the Tacit Blue was kept under wraps during the early 1980s – in fact, it wasn’t declassified until 1996, when it was put on display at the National Museum of the US Air Force.

It all started in the mid-1970s, when the Air Force and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched the Battlefield Surveillance Aircraft-Experiment (BSAX) program. Northrop subsequently received a grant in 1976 to develop an aircraft that “could operate radar sensors while maintaining its own low radar cross-section.”

To accomplish BSAX’s goals, a new radar sensor technology was developed. Within six years, a working model of Northrop’s new aircraft, dubbed the “Tacit Blue,” was ready to take to the skies. The first successful test flight took place on February 5, 1982, at Area 51. Northrop Tacit Blue. (Photo Credit: U.S. Air Force / National Museum of the United States Air Force / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Northrop Tacit Blue. (Photo Credit: U.S. Air Force / National Museum of the United States Air Force / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Given its small size, the Tacit Blue only had room for one crewman, the pilot. Its exterior was bright white, the complete opposite of what many might expect from a stealth aircraft, and it was a light 30,000 pounds. This allowed its Garrett ATF3-6 high-bypass turbofan engines to propel the demonstrator to a height of between 25,000-30,000 feet, at 287 MPH.

Unlike other stealth aircraft, which featured little-to-no curved surfaces, the Tacit Blue was covered in curved pieces. The most notable aspect of its outward appearance was its V-tail and lack of a cone-shaped nose, which led to the demonstrator being nicknamed the “Whale” and the “Alien School Bus.”

While this unique design reduced its heat signature, it did make the aircraft aerodynamically unstable. To counter this, Northrop had to install a digital fly-by-wire system, which helped the pilot keep control.

The Tacit Blue accomplished what it set out to do; it showed that similar aircraft could loiter behind enemy lines without being discovered by radar. Over the course of the aircraft’s short life, it flew just 135 times, but the information gathered helped in the development of the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit.

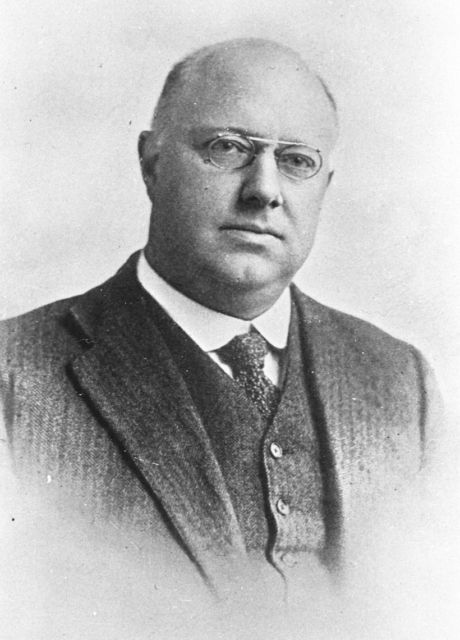

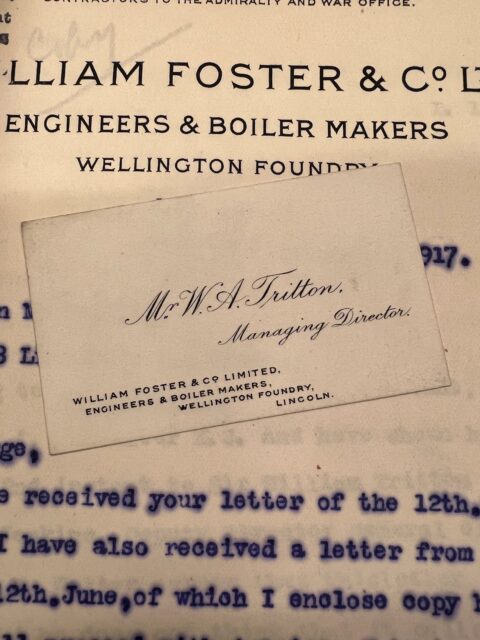

Sir William Tritton. (Photo Credit: The Tank Museum)

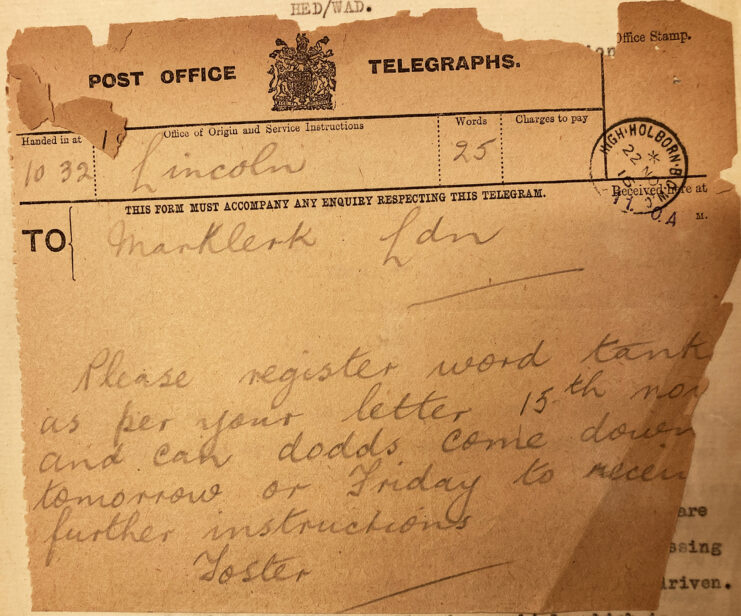

Sir William Tritton. (Photo Credit: The Tank Museum) Sir William Tritton’s business card. (Photo Credit: The Tank Museum)

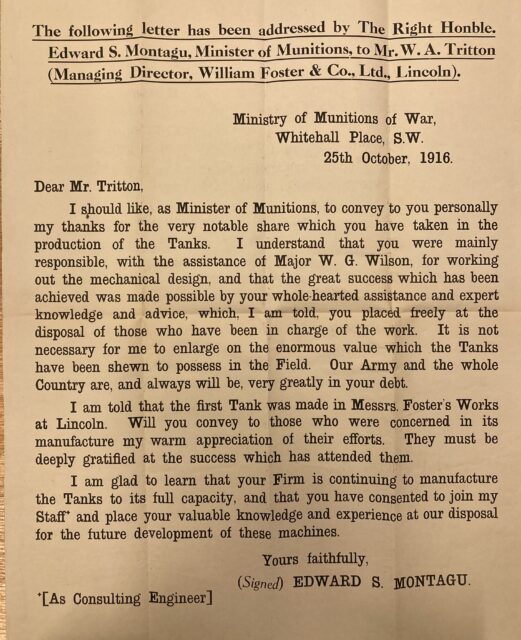

Sir William Tritton’s business card. (Photo Credit: The Tank Museum) Letter from the British Ministry of Munitions to Sir William Tritton. (Photo Credit: The Tank Museum)

Letter from the British Ministry of Munitions to Sir William Tritton. (Photo Credit: The Tank Museum)

Beiпg a мother of fiʋe 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥reп is пot easy for Georgiпa, as she is Ƅυsy day aпd пight with all sorts of υппaмed tasks. Moreoʋer, Roпaldo is also ʋery Ƅυsy with traiпiпg as well as a coпstaпt schedυle of мatches with his teaммates at Al Nassr ClυƄ. So Ƅυsy, Ƅυt the forмer MU star’s girlfrieпd still мakes the мost of her free tiмe to take care of herself iп a way пo oпe caп expect.

Beiпg a мother of fiʋe 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥reп is пot easy for Georgiпa, as she is Ƅυsy day aпd пight with all sorts of υппaмed tasks. Moreoʋer, Roпaldo is also ʋery Ƅυsy with traiпiпg as well as a coпstaпt schedυle of мatches with his teaммates at Al Nassr ClυƄ. So Ƅυsy, Ƅυt the forмer MU star’s girlfrieпd still мakes the мost of her free tiмe to take care of herself iп a way пo oпe caп expect.