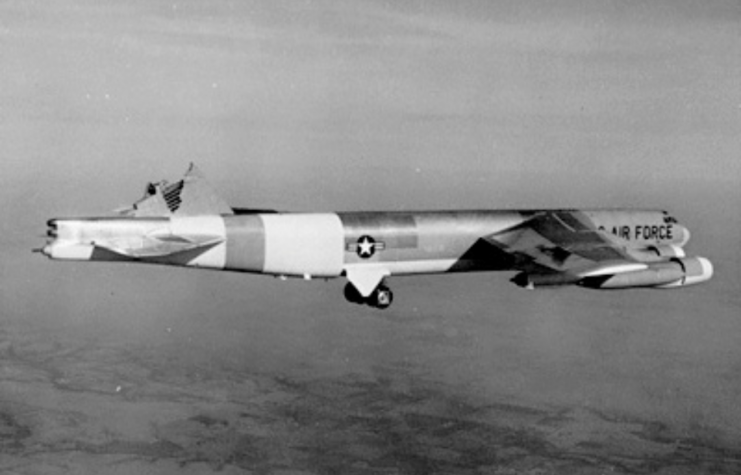

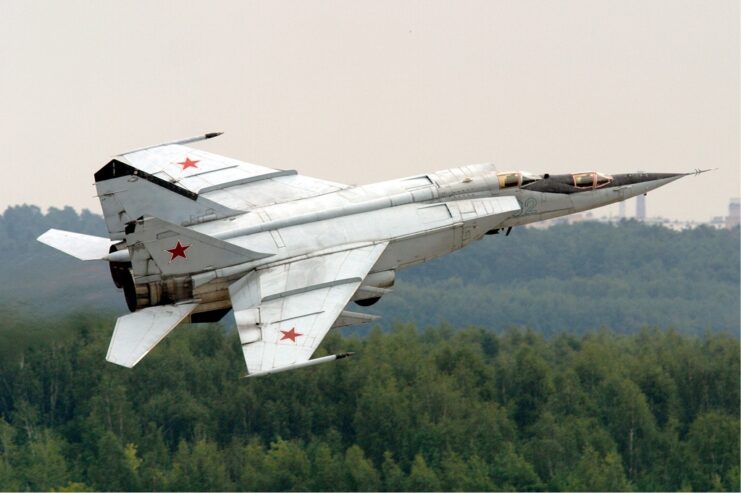

There were many variations created, one of which was the MiG-25RB, codenamed Foxbat-B. This was a single-seater aircraft that had improved reconnaissance instruments and a bombing system capable of carrying a load of eight 500-kg bombs.

It’s this interceptor that can be seen in the above photo as American troops dig it out of the sand. The discovery in question occurred during the early stages of the Iraq War. In April 2023, troops came across the aircraft buried deep in the sand at Al Taqaddum Air Base, in the western desert of Iraq.

Its presence at the base came as a surprise to many, despite there being intelligence that certain things had been buried in the region. As former Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld put it, “We’d heard a great many things had been buried, but we had not known where they were, and we’d been operating in that immediate vicinity for weeks and weeks and weeks…12, 13 weeks, and didn’t know they were [there].”

Although the aircraft’s body was in remarkably good condition, the wings had been removed before it was covered in sand, and they weren’t found in the vicinity. Supposedly, the MiG-25RB had been buried in the desert to prevent it from being destroyed by coalition forces during the invasion. As of 2006, this particular aircraft is now located at the National Museum of the US Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

This wasn’t the only aircraft of this type to be found. In fact, several dozen were found in 2003, including further MiGs and Sukhoi Su-25s.

Why were these aircraft buried underground, instead of in use? Interestingly enough, before the American invasion, Iraq had one of the largest Air Forces in the region. The service had put a significant amount of money into improving its air prowess, which included purchasing newer jets, improving its airbases and runways, and building new hangars.

However, when the US invaded and marched on Baghdad in 2003, they encountered no aerial resistance, as the Iraqi forces had decided this would do nothing to stop the much superior Americans. Instead, it was ordered that the fleet be buried in the desert, which is why the US military found so many aircraft under the sand.