More than 3200 miles northeast of Sydney, Australia, near the remote Phoenix Islands, marine biologists were conducting an expedition, led by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, to get a more complete picture of the region’s overall ecosystem and how seabed habitats are interconnected. Rather unexpectedly, they came across one of the rarest octopuses, the Vitreledonella richardi, also known as the glass octopus.

Prior to the Institute’s expedition, good quality footage of the animal was quite limited, and studying these cephalopods was mostly possible by examining the remains of specimens that were found in the guts of other sea predators. Glass octopuses, like other deep dwelling ocean creatures, aren’t really easy to come by since they live in the ocean’s 3,000 feet deep “midnight zone”. Also known as the aphotic zone, this part of the ocean is famous for being the world of total darkness. Only less than 1 percent of the sunlight penetrates these depths, which actually make up most of the ocean waters.

So, the fact that the expedition team encountered the creature not once, but twice, is quite amazing. These sightings are the result of more than 182 hours of expedition dives with the remotely operated underwater vehicle SuBastian, which can reach depths up to 2.8 miles (4500 meters).

Although the species was discovered in 1918, we know very little about its life cycle and habits besides that they seem to grow up to about 1.5 feet (46 centimeters) long and are estimated to live about 2-5 years. In previous studies, females have been shown to lay hundreds of eggs in the mantle cavity, and since there is almost nowhere to hide in the open water where glass octopuses live, they seem to take the eggs with them until they hatch.

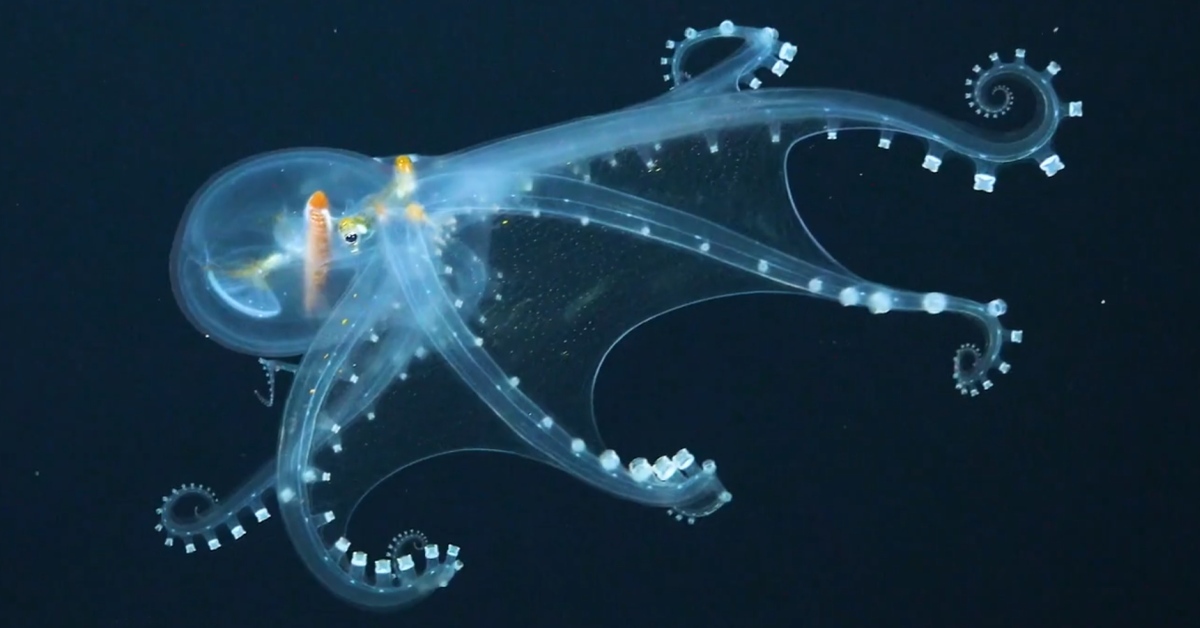

The name “glass octopus” refers to the creature’s body, which is almost totally transparent except for the optic nerve, eyes and digestive tract, which they can’t make transparent. It is thought that its transparency makes its body less visible to both prey and predators, but this is not the only thing that sets it apart from other octopuses.

Unlike many other octopuses, which have large, round eyes that can cover roughly 180° on one side of the animal, increasing their field of vision, the glass octopus has odd, cylindrical eyes. According to research published in the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, this shrinks their peripheral vision, but also makes it more difficult to spot the eyes from below, making these animals even less detectable to predators.

Coming across the two Vitreledonella richardi specimens wasn’t the only groundbreaking finding of the expedition; the scientists also identified marine species and organisms not yet discovered before, and gathered footage of whale sharks, which are also not seen every day, as well as crabs stealing food from each other.

Furthermore, they conducted the world’s first comprehensive survey of coral and sponge predation. Their goal is to determine how corals respond to scars and injuries, using a novel series of experiments and creating the largest collection of deep-water microbial collection in the central Pacific through this work.

As Wendy Schmidt, co-founder of Schmidt Ocean Institute, wrote:

“The Ocean holds wonders and promises we haven’t even imagined, much less discovered. Expeditions like these teach us why we need to increase our efforts to restore and better understand marine ecosystems everywhere–because the great chain of life that begins in the ocean is critical for human health and wellbeing.”

Sources: 1, 2