A mythical sea monster has been demythicized.

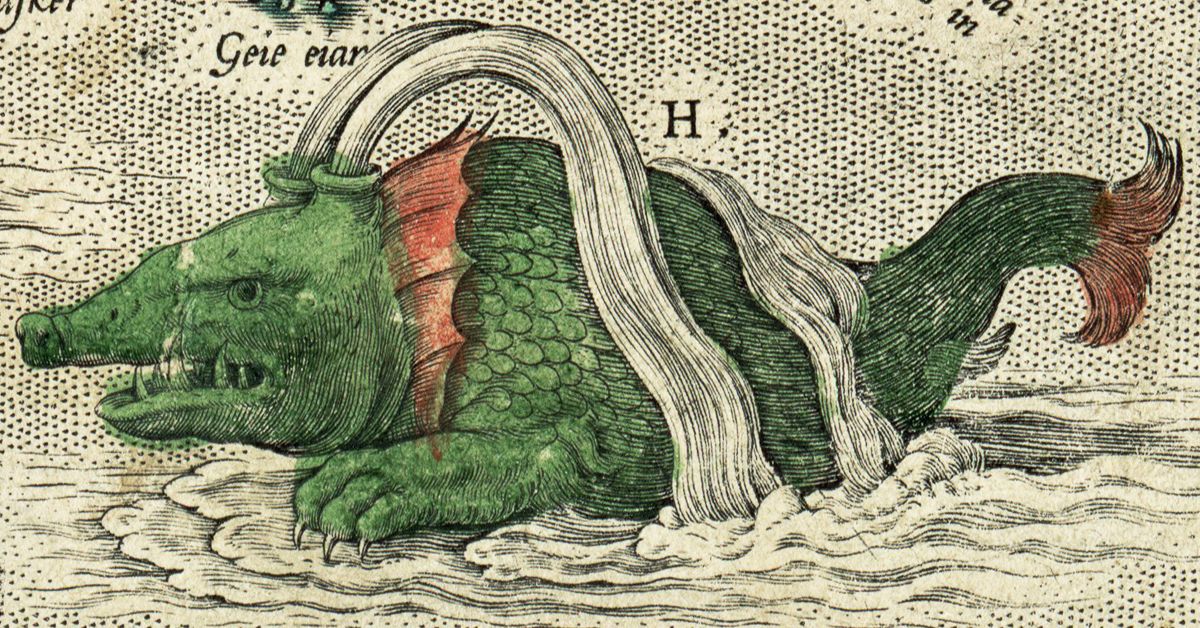

Maps from ancient times showcased illustrations of incredible sea monsters and the phrase “here be monsters,” as a way of warning sailors about the potential dangers of the ocean. These monstrous creatures, with their fierce teeth and numerous tentacles, were meant to warn sailors of the perils that lay beneath the waves. But what was the reason for mapmakers to include such ominous creatures in their representations of the world’s waters? Was it just an artistic choice or did it have a more profound significance? Recent recent suggests the latter, giving us insight into what one of these mythical creatures may have actually been.

According to a recent study, the ‘hafgufa’ – a sea creature referenced in 13th-century Old Norse documents, which was initially believed to be a mythical monster akin to the Kraken – is a whale employing a hunting method called trap or tread-water feeding.

Whales sometimes swim to the surface, open their mouths, and wait for a school of unsuspecting fish to swim in. At this time, their upper jaw is raised high towards the surface of the water, which, according to the chronicles, already caught the eye of the Vikings, but researchers only observed this behavior for the first time in 2011. The Norwegian sailors of the 12th century thought that they were seeing the hafgufa, while the researchers assumed that the animals adapted to the changing ecological conditions.

The peculiar behavior was observed in two independent studies of two species, the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) and the Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera brydei), and shows an eerie resemblance to the hafgufa, which researchers have traced back to a second-century A.D. text from Alexandria titled “Physiologus.” This text includes illustrations of a whale-like creature known as the “aspidochelone,” with fish jumping into its open mouth.

In 2021, a BBC documentary series showcased a video clip of a Bryde’s whale using this tactic, which subsequently went viral on Instagram.

View this post on Instagram

“I was reading some Norse mythology and noticed this creature, which resembled the viral whale feeding behavior,” John McCarthy, a maritime archaeologist in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University in Australia, told Live Science. “Once we started to investigate a bit further, we noticed the parallel was really quite striking.”

A collaborative effort between marine biologists, archaeologists, and experts in medieval literature and language sought to explore the parallels between the hafgufa and this way of whale feeding. The findings were published in the journal Marine Mammal Science.

According to the study authors, it is highly likely that medieval sailors were aware that the hafgufa was a species of whale, and not an actual sea monster. The researchers found one of the most compelling examples from ancient texts in a document called Konungs skuggsjá, or “The King’s Mirror,” which was composed for a Norwegian king in the 1200s and was probably an effort to compile a reference work akin to contemporary encyclopedias. The document contains the following account of a hunting technique that bears a striking resemblance to modern observations of trap or tread-water feeding by whales.

“It is said of the nature of this fish that, when it goes to feed, it gives a great belch out of its throat, along with which comes a great deal of food. All sorts of nearby fish gather, both small and large, seeking there to acquire food and good sustenance. But the big fish keeps its mouth open for a time, no more or less wide than a large sound or fjord, and unknowing and unheeding, the fish rush in in their numbers. And when its belly and mouth are full, (the hafgufa) closes its mouth, thus catching and hiding inside it all the prey that had come seeking food.”

According to the study, the “belch” mentioned in the text could pertain to how rorqual whales strain their food, spewing out a portion to attract additional prey into their mouths. Additionally, the researchers highlighted that the process of whale feeding is often accompanied by a foul odor resembling that of rotten cabbage.

So, the ancient description is surprisingly accurate, according to McCarthy, but that is by no means surprising: the King’s mirror was intended as a serious reference work, and although early natural science descriptions are often incomplete and contemporary scientists filled in many details with their imaginations, it points to an existing feeding strategy.

McCarthy concluded that research clearly shows how important a meaningful reading of medieval and early natural science sources can be: researchers should start from the fact that the descriptions were compiled by intelligent people, and it does no harm to pay attention to what they observed – from this it may even turn out that a feeding strategy thought to be new has actually always existed.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6