Conditions were perfect for a stalk. The hunters followed a little ridge for cover until they got to a rock to hide behind. There was only room for the client to crawl atop and, when he did, the bear was only 15 yards away. The first shot tore through the animal’s shoulders. The bear stood up on its hind legs and stared downstream looking for whatever had hurt him. Another shot or two and the bear was down. He wasn’t quite the biggest Baertle had taken but, he was close. The old boar measured nine and a half feet with a skull just shy of 26 inches.

A few days later, Baertle brought the bear’s skull and hide to be sealed by Fish and Game in Juneau. The biologist saw the collar scar and hole in the ear where there had once been a tag and realized it was a “research bear.” Afterward, Baertle went to FedEx and was about to ship the hide and skull to a taxidermist when Fish and Game called asking if he could come back. Baertle complied, and when he walked into the office he found brown bear expert LaVern Beier waiting for him. Beier had participated in capturing and collaring around 250 brown bears on Admiralty Island. Even though this bear was killed a little outside of Fish and Game’s roughly 140-square-mile research area, Beier knew it was one of his bears. For every bear he captured, Beier had taken meticulous notes and photos so if he encountered that bear again, he’d be able to identify it. Beier examined the hide and skull, noting the teeth were cracked but still in fairly good shape. He spent two days going through his notes. What Beier figured out surprised everyone, including himself, and made him reflect back to the beginning of his career.

Bear Man Beginnings

In 1970, when Beier came to Alaska at the age 17, he had no inkling his life would become intertwined with brown bears. He got talked into, or, as he puts it, “brainwashed” by legendary outdoorsman Bruce Johnstone into forming a trapping partnership with the old timer up the Unuk River. Wise in the way of the woods, Bruce took on Beier as his understudy. In their third season trapping together, Beier had his first life and death encounter with a brown bear while he was trapping beaver. Normally, bears are remarkably tolerant of people and go out of their way to avoid conflict, but there’s the occasional bear that is looking for a fight—or looks at humans as prey. Beier was lined up to shoot a beaver when he heard something behind him. He turned to see an adult male brown bear coming for him. He swapped his .22 for his .338 and yelled to try to stop the bear, but the bear kept coming. It took four shots before it went down.

A few months later, Beier took his first job with Alaska Fish and Game, where his job was to patrol the bays around south Admiralty Island for illegal commercial fishing. All was not well on the brown bear island wilderness. The Forest Service was on the verge of selling off the island to pulp mills to be clearcut. That summer Beier met Jack Aldrich, the creator of the Aldrich bear foot-snare, who’d just completed his third season working with biologists Harry Merriam and Bob Wood on the other side of Admiralty Island. They’d been foot-snaring brown bears to try to get some baseline data before the island was logged. Aldrich and Merriam captured around 30 bears. They had two early homemade VHF radio collars but neither worked. They’d learn the movements of their captured and tagged bears based on where hunters killed them or, if they got lucky, by spotting bears with ear tags in the spring when they were on beaches. A few years later, Aldrich taught Beier the art of foot-snaring bears. Utilizing the Aldrich foot-snare was considered the most feasible methods for capturing bears in the temperate rainforest of Southeast Alaska.

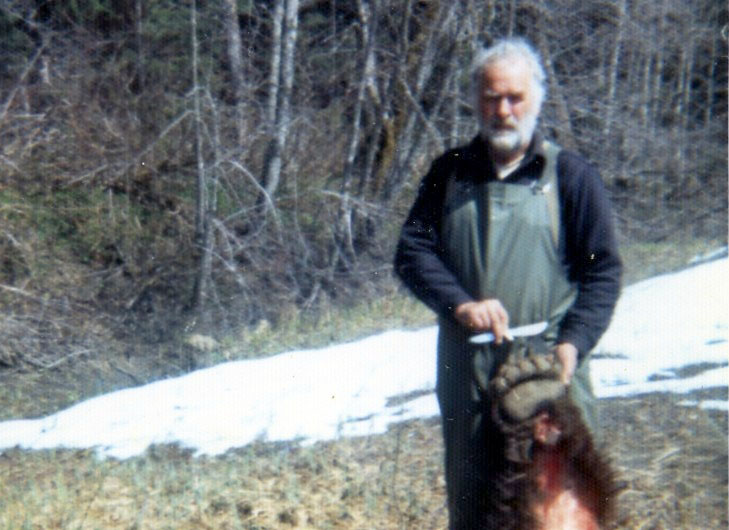

Beier worked for Fish and Game seasonally; he’d trap in the winters and guide bear hunters in the spring and fall. He worked nine years for Karl Lane, a master guide who fought tooth and nail to save Admiralty Island. Beier shares Lane’s conservation ethic and to this day is a staunch advocate for brown bears. He received criticism from some over being both a bear hunter and researcher, but the biologists he worked with supported him.

“I always viewed bear hunting as bear research. There is far more bear watching than bear killing. A lot of biologists don’t know bears being bears. They don’t know bears on the ground. They know bears from helicopters, airplanes and their data,” Beier says.

In 1980, Beier got hired to do brown bear research on Admiralty Island. President Jimmy Carter had protected a significant portion of Admiralty. However, outside the designated wilderness boundaries, the island’s resources were being exploited. The Greens Creek Mine, one of the largest silver mines in the world, was about to be built on the northern portion of Admiralty. In August 1981, Beier, biologist John Schoen and a couple of other researchers went to snare brown bears on salmon streams to get baseline data before the mine went in. It was a big learning curve, and it wasn’t long before Beier was forced to kill a bear in self-defense.

“We wondered if it was even possible to foot-snare and capture bears safely,” Beier says. “We stopped and reassessed what we were doing.”

Some bear biologists at that time doubted they’d be able to track the bears movements across Admiralty with VHF transmitters in the dense temperate rainforest. But still, the team went back to snaring and they successfully put the first VHF transmitter on a bear in Southeast Alaska. They fitted around 10 transmitters on bears that August. Through telemetry flights, they learned many bears were moving into the alpine after salmon runs petered out. Later that September, they successfully darted a brown bear from a helicopter in the alpine—a feat that until then many thought was impossible in Southeast Alaska. They learned a lot, both about brown bears habits and how to work with them. At the time, the drugs they were using to sedate the bears were dangerous for the animals as well as the people using them. It was easy to accidentally kill a bear with drugs. Or, if the bear was not properly sedated, it was easy for a person to be hurt by a bear. There were other unexpected factors to contend with. For instance, once, after Beier and John processed a female bear in the alpine, they left and a male bear came along. The female had been in estrus and when she hadn’t responded to the male’s advances, he killed and ate her.

From 1981 to 2004, Beier captured hundreds of brown bears on Admiralty Island and nearby Chichagof Island. The two islands, as well as Baranof Island, Kruzof Island and Yakobi Island, are part of the ABC Islands. All have similar ecosystems, but Admiralty and Chichagof have the densest populations of brown bears. Beier worked with deer, mountain goats, elk, wolves, as well but brown bears were his expertise. In 2001, he switched from VHF to GPS collars, which turned out to be game changers. In a good year a researcher might get 12 data points from a bear wearing a VHF collar; with a GPS collar they found they could get 2000 data points in a couple of months. It showed them types of movement they had no idea occurred. It was during this transitional time period that Beier had one of his most unusual and unsettling scenarios snaring bears.

Rogue Bears and Close Calls on Chichagof Island

Twenty years of foot-snaring brown bears had honed Beier’s skills and knowledge. When he would consider setting a snare he’d look for signs of cubs. The worse case scenario was catching a cub, which would enrage its mother. If there was sign of cubs, Beier might not make a set. He also modified the Aldrich snare so that in theory it wouldn’t catch small bears unless the snare threw high on the animal’s leg. Beier made sure there were safe vantage points to check snares from a distance. As he approached a set, he’d sometimes spend an hour watching the bear with binoculars to confirm how well the bear is caught and its general attitude. If there were multiple bears, he needed to figure out which one was in the snare and then decide on the safest plan of action.

“We try to go above and beyond to not hurt animals,” Beier says.

In 2002, the brown bear project leader biologist Jack Whitman, agreed to help a National Geographic film crew try to fit a brown bear with the first crittercam, which would show audiences the world from the bear’s perspective. Beier was on Chichagof Island working with another biologist and they started snaring bears a few weeks before the crew showed up. They had caught and processed around 20 animals when they moved to Kennel Creek to set a few snares. There were some salmon around but the main run hadn’t arrived. The following morning, when the men returned to check their sets they saw a motionless bear caught in the first snare. It’s not unusual for bears to fall asleep in a snare, but after studying the animal with binoculars they noticed flies and then blood. They found the bear dead from bites to its head, lying on its back, its genital area torn up from another bear.

“We were stunned. This was something new. We went down the creek to check the other two snares and, fuck, there was another big dead bear. Nothing consumed. The sexual area torn up again,” Beier says.

They pulled out of Kennel Creek, hoping that when the flood of salmon came in the rogue bear would calm down and become preoccupied with catching salmon. A week later, after the salmon had arrived, Beier and Steve returned to Kennel Creek and set two snares near where the first bear had been killed. They came back the next day and in the first snare there was a dead bear lying on its back with its groin torn-up. The next snare held a big dead female bear that was buried beneath a mound of gravel. Only her front paws stuck out of the gravel bar. The men finally saw the track of the bear responsible.

“Suppose he was the biggest bear on Chichagof? He wasn’t. Maybe an 8-footer. It was not food driven. It was a power thing. I decided if I saw the Kennel Creek Killer, I was going to kill it. I didn’t give a shit if I got in trouble, this was one twisted bear,” Beier says.

The next day the National Geographic film crew arrived and promptly suggested putting a camera trap that could be viewed in real time from a distance on the buried bear. When they returned to where she’d been cached she was gone. There were no drag marks. Beier estimated she weighed between four and five hundred pounds. A bear, most likely her killer, had lifted her clear and carried her off into the forest.

The men left Kennel Creek to go work a creek three miles away, which they assumed would be safer. They made 6 sets, then came back the next day to check them. It was raining hard and the sounds of the rapidly rising creek and vegetation being splattered drowned out most other sounds. Early in the morning, at their first set, they found a bear asleep on a log jam. Once immobilized, Beier noticed she was lactating but didn’t see or hear any signs of cubs. In the early evening, after they finished checking the other snares and processing another bear, Beier began leading the crew back. They were in bear central—it’s not rare for there to be 30 or more brown bears on a mile of salmon stream on Chichagof Island. Beier made sure to give the areas where he’d left the sedated bears plenty of space. In a dense alder patch, Beier heard a bear roar and then charge. It was the first bear that they’d caught early in the day. In hindsight, Beier figured the bear had cubs and was trying to find them. The heavy rain had washed away the cubs’ scent and she was desperate and mad when the crew ran into her. In the jungle like rainforest Beier always carries a machete and he used it to try to hold her off, thinking the residual influence of the drug might make her manageable. Beier was wearing a heavy pack and became tangled up in the vegetation before the bear knocked him down and pinned him to ground. He had to hold his .338 to the side so he didn’t blow his foot off when he fired.

“I lay on that bear and cried. I apologized to her. I lay on that bear as it breathed its last breath. Saying…I was so sorry, we are here to help you not hurt you,” Beier said.

The Oldest Bear

By the time Hans Baertle the hunting guide brought in the hide and skull of the bear his client had killed in 2015, Beier had captured and handled over a thousand bears. He’d survived four brown bear attacks. Based on his involvement with DNA research work, he knew the nine distinct populations of brown bears in Southeast Alaska better than anyone. Of the thousands of brown bears Beier had encountered, Baertle’s bear was special. It was one of the first bears that he had and biologist John Schoen had darted from a helicopter in 1981. A few years later, Schoen and Beier had recaptured the bear and swapped collars. The bear had established its home range just outside of the researchers’ study area, on land owned by a Native Corporation, which explains why Beier lost track of it. The bear was 38 years old, making it potentially the oldest known wild brown bear.

“All the changes he lived through…His home range was initially old-growth forest and then it was all logged. Something like 23,000 acres clearcut. Besides his teeth, he was in great shape. He would have lived a while yet if he hadn’t died from lead poisoning,” Beier said.

Beier retired from Fish and Game in 2016. He’s still invested in bear research and conservation. Among other things, in 2018 he was part of team to that went to Mongolia to study the extremely endangered Gobi brown bear. He’s been working on two books, which many people (this writer included), are looking forward to reading.

Bjorn Dihle is a lifelong Southeast Alaskan. His most recent book is A Shape in the Dark: Living and Dying with Brown Bears.