We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

My tenure for the past decade as a western big-game guide, combined with a lifetime obsession for hunting, puts me in the field over 150 days a year. From ground squirrels to lovesick spring toms, bugling bull elk, and a smorgasbord of feathered and furred quarry, the Mountain West provides ample opportunity to hunt year-round. And since I am in the mountains or a duck blind so frequently, there are a few trusted guns I rely on. Of course, the following firearms are not the only guns you can use to hunt the West, but they have all served me extremely well. And if you’re trying to line your gun cabinet with the proper firearms to hunt all western game species, these rifles, shotguns, and pistols will get the job done.

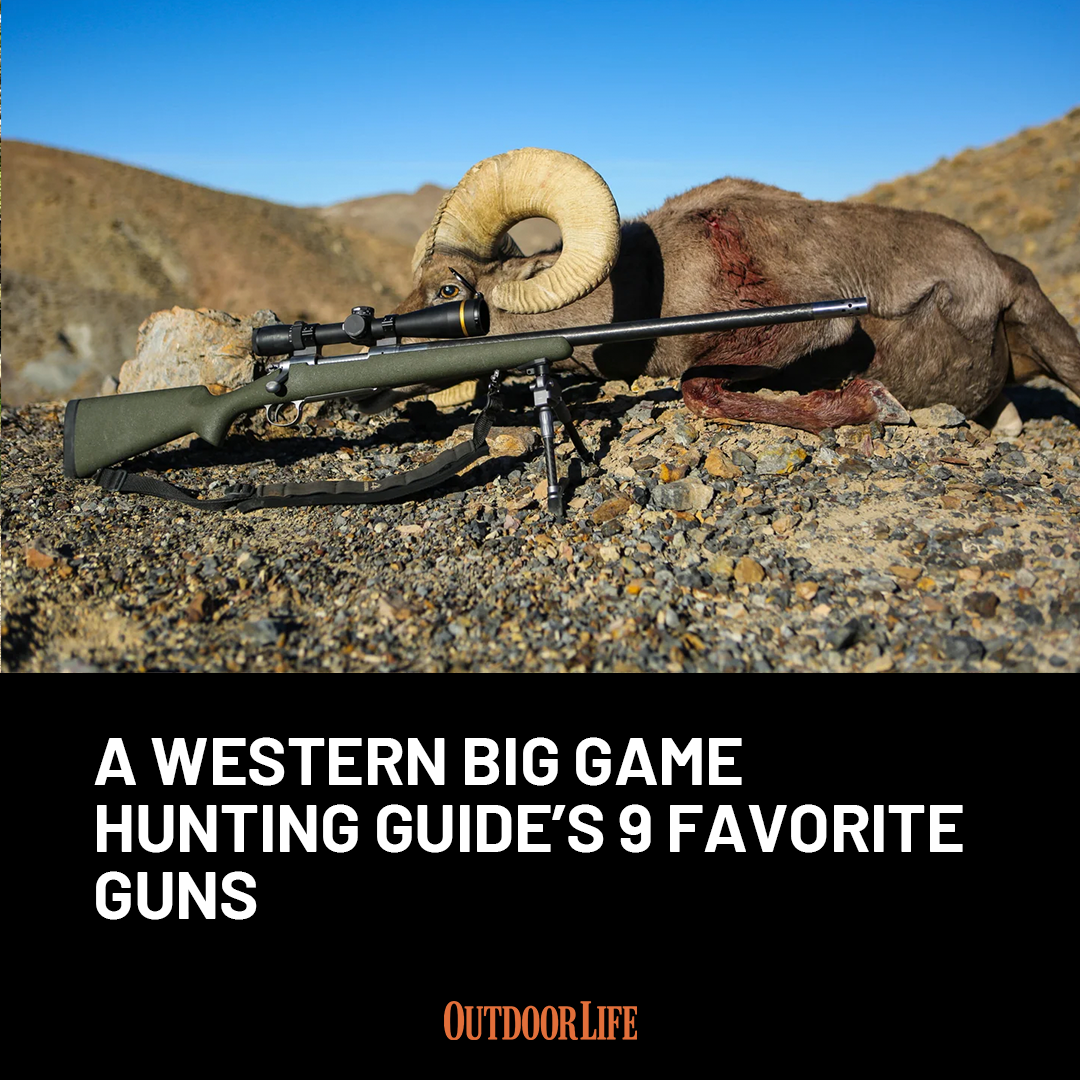

Deer, Sheep, and Antelope Rifle: Custom Remington 700 .280 Ackley Imp.

A capable centerfire rifle is a necessity to hunt the wide diversity of ungulates found across the West. The popular .300 Win. Mag. will certainly kill any big-game species you need it to, but I prefer having at least two different rifles: One rifle for deer and antelope sized game and another for larger critters such as elk, bear, and moose. I would classify any cartridge between the .243 Win. and the variety of .284 offerings plenty adequate for deer and antelope. My current go-to centerfire is a custom rifle chambered in .280 Ackley Improved. This decked out, custom build features a Remington 700 action, PROOF Research carbon fiber wrapped Sendero Light barrel, PROOF Research Mountain stock, and a Timney H.I.T. Trigger set at 2.5 pounds. Leupold’s VX-6 HD 3-18X44 scope puts the cherry on top of this build, which tips the scales at just under 8 pounds. The .280 Ackley Imp. is an inherently accurate cartridge, but this tack driver of a rifle consistently shoots .50 MOA groups with Federal’s 155-grain Terminal Ascent factory offering. I’ve shot desert sheep in Nevada, pronghorn in Wyoming, and several Texas whitetails with this rifle. It has never let me down.

Elk, Moose, and Bear Rifle: Browning X-Bolt McMillan LR .300 PRC

Assuming you are shooting a well-constructed bullet, any cartridge between .284 and .338 are proven to be deadly on big-boned game such as elk and moose. Can both species be killed with smaller cartridges? Absolutely. In fact, I cleanly killed a mature bull at 365 yards with a single 162-grain Winchester Copper Impact bullet last year with Browning and Winchester’s new 6.8 Western cartridge. However, my time as a guide has taught me that these smaller cartridges do not leave as much margin for error as larger ones (but you also must be comfortable with the amount of recoil a heavier bullet produces in order to be accurate with it).

See It

With that in mind, my current set-up for hunting elk and black bear is Browning’s X-Bolt McMillan LR chambered in .300 PRC. My only complaint about this rifle is it is slightly heavier (over 8.5 pounds with scope and fully loaded) than I am used to carrying, but the weight certainly helps suppress felt recoil. Shooting 190-Grain Hornady CX bullets, this rifle regularly rings steel at 1,000 yards and carries plenty of terminal knock-down power beyond 500 yards.

Short-Range Rimfire Rifle: Ruger 10-22

Rimfire rifles provide valuable training opportunities to hone your marksmanship. They are also effective varmint and small game guns. When I hunt ground squirrels, prairie dogs, and rock chucks, my rimfire of choice is a Ruger 10-22 that belonged to my grandfather. It’s not the prettiest gun, but I’ve hunted with it more than all the other rifles in my safe combined due to its durability and accuracy. I have had the 10-22 for 30 years, and with my son showing a budding interest in hunting I look forward to the day that I will get to pass this rifle on to him. Hopefully he will find as much joy in it as I have.

See It

Long-Range Rimfire Rifle: Savage 93R17 BTVSS .17 HMR

The second rimfire I take afield, especially when shooting rock chucks or taking 100-plus yard shots on prairie dogs, is a left-handed Savage 93R17 BTVSS .17 HMR. The .17 HMR cartridge is an effective killer on small critters and can take out coyotes as well. The Savage is also incredibly accurate, putting holes inside holes when shooting off a bench. This sweet little rifle doubles as a rabbit gun, though a head shot is a must to preserve the little meat that is on them.

See It

Duck Hunting Shotgun: Winchester Super X3

By and large the vast majority of waterfowlers shoot either a pump or semi-auto 12-gauge shotgun to take advantage of larger payloads and the ability to shoot three shells. Both platforms are also easier to load and unload when you’re hunting from a blind. My waterfowl gun collection has grown in recent years, but the one I grab most often is the Winchester SX3.

See It

The gas-driven action of the 3½-inch SX3 has cycled every shotshell I have ever put through it. But more importantly, I shoot the gun well. The SX3, a favorite among snow goose hunters for its soft recoil and functionality, features a Dura-Touch coating that protects the shotgun fromthe constant abuse and corrosion duck hunters put their guns through.

Upland Shotgun: Browning Citori Lightning

See It

Over/under shotguns go hand-in-hand with upland bird hunting. There are many great O/U options, but the one that has always trumped them all for me is the Browning Citori, an affordable break-action platform that is available in a gauge and price point to fit most hunter’s needs and means. My first Citori was an older model 20-gauge Lightning. It now proudly wears the dings and dents of years of use and abuse from hunting across the West. I shoot a sub-gauge because shots are typically close and upland birds are easier to bring down than ducks and geese, so you can get away with smaller payloads. Sub-gauge shotguns are also lighter than a 12-gauge, which makes a big difference when you’re climbing steep faces for mountain chukar.

Turkey Shotgun: Benelli Super Black Eagle

Tungsten Super Shot (TSS) has changed the game for turkey hunters, making even a dainty .410-bore a legitimate gun to kill longbeards (where legal). But paying over $10 per shell is not an option for many hunters. And if you hunt turkeys the way I do—calling them in close—TSS isn’t a necessity. That’s why my turkey gun has been an original inertia-driven 12-gauge Benelli Super Black Eagle for years. Although there are plenty of aftermarket choke options, the factory full in this classic auto-loader paired with Winchester’s 3-inch Longbeard XR No. 5s has patterned best for me. It’s capable of killing a turkey at 50 yards, though I don’t need to take shots at that distance.

Truck Gun: Christensen Arms CA-15

Most western hunters have a dedicated truck gun. Mine is a Christensen Arms CA-15. During the fall this rifle rides shotgun with me always, primarily to shoot coyotes. The CA-15 is light, accurate, and the collapsible stock makes it easy to store or keep out of the way inside my vehicle. Hornady’s Varmint Express ammo, loaded with a 55-grain V-MAX bullet produces the most consistent groupings for me, typically around 1 MOA. I consider that good enough for and AR I shoot out to 300 yards. My rifle scope of choice on this coyote exterminator is Leupold’s bomb-proof VX-3 HD 4.5-14X40. The low end of magnification on the scope allows for quick shots when calling predators in close quarters, while the top end still allows me to reach out if a wary song dong hangs up. This rifle also doubles as a great rock chuck gun when I don’t have a rimfire handy.

See It

Personal Defense Pistol: Springfield XDS .45 ACP

Living in Utah, I never felt it necessary to carry a sidearm while hunting to protect myself, but that changed a few years ago. I was scouring the hills in search of shed antlers when I crested a ridge and came face-to-face with a mountain lion. The lion never showed aggression, but we had a stare down inside 100 yards that I vividly remember. As I slowly walked backwards, I felt helpless without any way to defend myself. Luckily the lion stayed put, but that week I made my way down to the local gun store and purchased a Springfield XDS chambered in .45 ACP that rarely leaves my side.

See It

The XDS weighs a mere 21.5-ounces and sports a 3.3-inch barrel, making it easy to carry in the backcountry. One downside to the XDS is its single-stacked magazine capacity of 5+1. It would be nice to have a few more rounds to send downrange in a pinch, but on the rare occasion that I will ever have to use this sidearm, I believe I am accurate enough to subdue a threat with six shots. Like home defense weapons, any soft or hollow point ammo is sufficient for personal defense from lions or black bears (I don’t run across grizzly bears often). If you are hunting in grizzly country, you are better off shooting a solid cast bullet that could penetrate the dense skull of a bear. A personal defense pistol adds weight but provides peace of mind knowing that I have fire power close by if an emergency were to arise.