We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The performance gap between compound bows and new crossbows seems to be widening exponentially. In last year’s Crossbow Test, for example, we reviewed two bows—the Ravin R500 and TenPoint Nitro 505—that shot speeds faster than 500 fps, which was impossible to imagine just a few years ago. For reference, the fastest compound bow in the 2022 Bow Test—the Bowtech SR350—generated a speed of 288 fps with a 67-pound draw weight, 29-inch draw length, firing a 450-grain arrow. That difference of 200 fps is so substantial that many bowhunters still argue that crossbows don’t belong in regular archery seasons. Many of us also wonder when crossbow advancements might begin to plateau or when game agencies might crack down on crossbow performance.

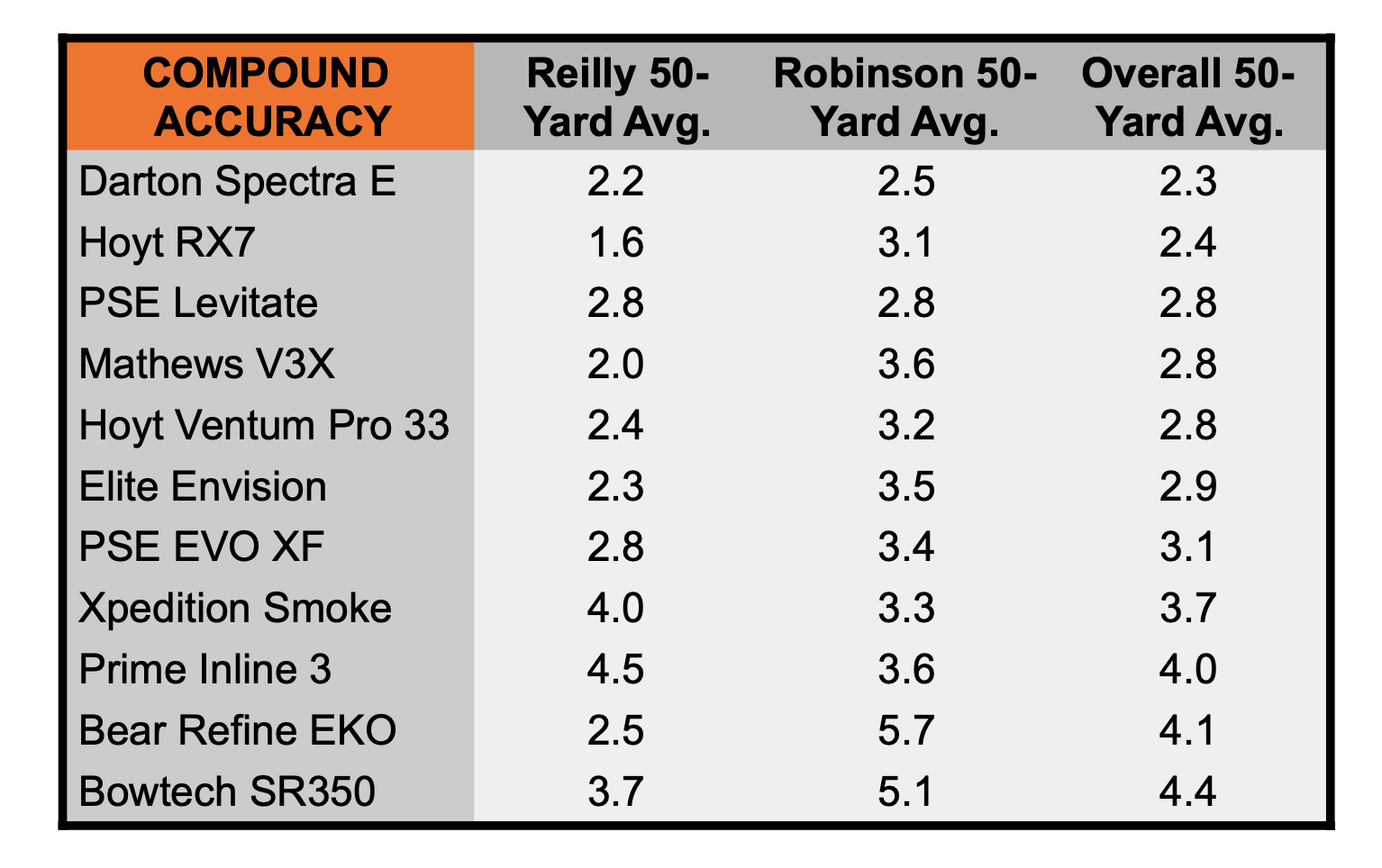

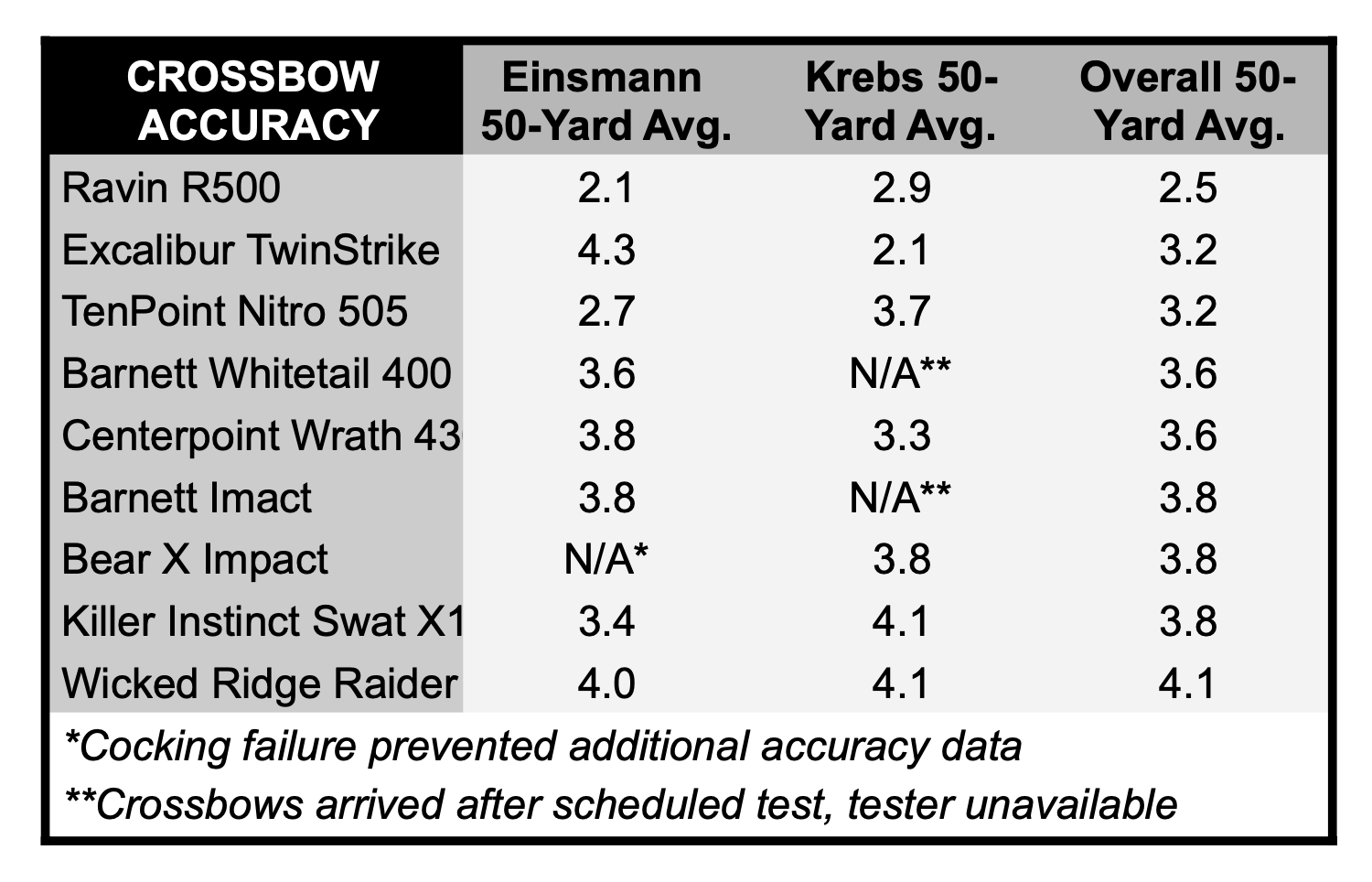

But there’s one critical metric where crossbows and compound bows are much closer than most bowhunters realize: accuracy. We shot the field of new crossbows and compound bows at Lancaster Archery and Supply’s 50-yard range. Crossbows were scoped up, dialed in, and shot from a lead sled. Compound bows were paper tuned and shot without any stabilizers. Our test team included four shooters with varying degrees of experience. The results? The average three-shot crossbow group for the field was 3.45 inches. The average three-shot compound bow group for the field was 3.20 inches. Yep, at 50 yards, the compound bows were more accurate, on average.

Digging Into Crossbow vs. Compound Bow Accuracy Data

What we were really testing here was field accuracy: how accurately a regular archer can actually shoot the bow or crossbow in the real world. If we’d have shot the bows out of a mechanical shooting device, like a Hooter Shooter, we’d likely get different results. But for bowhunters, the thing that matters most is the question: “How well can I shoot the bow?” So that’s what we measured.

We didn’t stack the deck in favor of compound bows with professional shooters, either. The compound bow testers were myself and P.J. Reilly of Lancaster Archery. Reilly is an expert shooter and veteran bowhunter. In other words, if you put him on a random public archery range he’d likely be the best shooter on the line, but he’s not winning national 3D tournaments. As for me, I’m a workaday archer. I’ve been bowhunting since I was 14, and I shoot diligently every summer so that I’m ready to be a lethal hunter in the fall. I don’t compete, I hang my bow up for the winter, and I’ve never had formal coaching. In other words, I’m probably just like you. Here’s how we shot.

We also both shot the underrated Darton Spectra E exceptionally well (2.17 inches for Reilly and 2.5 inches for me). This was our best-shooting bow at 50 yards, and it was as or more accurate, than the most accurate crossbow in the test.

Senior deputy editor Natalie Krebs and gear editor Scott Einsmann tested the crossbows under ideal conditions: from a lead sled resting on a heavy picnic table, in minimal wind. The most accurate crossbow from the field of nine was the Ravin R500 with an average group size of 2.48 inches. (Read the full review of the best crossbows of 2023 here).

If we parse out the data, and look at each shooter with each bow individually, some more interesting points arise:

- Best overall compound group: Mathews V3X, .75 inches

- Best overall crossbow group: Ravin R500, 1.06 inches

- Best overall 3-group average, compound: Hoyt RX7, 1.62 inches

- Best overall 3-group average, crossbow: Ravin R500, 2.06 inches

- Worst overall compound group: Bear Refine Eko, 6 inches

- Worst overall crossbow group: Killer Instinct Swat X1, 5.7 inches

- Worst overall 3-group average, compound: Bear Refine Eko, 5.67

- Worst overall 3-group average, crossbow: Excalibur Twin Strike X1, 4.27 inches

The takeaway? The most accurate compound bows beat the most accurate crossbows. But the least accurate crossbows beat the least accurate compound bows. Below, you can see our average three-shot groups with each bow and crossbow. —A.R.

Why Modern Compound Bows Are So Accurate

One of the biggest innovators in compound bows is Rex Darlington, who helped shaped compound bows into the tack drivers we know today. He also designed the most accurate bow we shot at the Outdoor Life Bow Test, the Darton Spectra E. You’ll find Darlington’s patents used in just about every flagship bow, especially his synchronized cam system.

“That cam system takes away a lot of the issues the shooter creates,” Darlington says. “It contributes a lot to the consistency and accuracy of the bow.”

One way it makes bows accurate is by eliminating nock-travel issues. Anyone who shot an early cam ½ system can appreciate the headaches the synchronized cam alleviates.

You might think that an arrow shooting from full draw travels in a straight line, but in some bow designs the nock end would move at an angle. In the worst designs, it would travel at an inconsistent angle. To solve the inconsistency issue, many archers timed their cams for a little downward nock travel to give the arrow a consistent direction. Another issue was that with each draw length adjustment, the nock travel changed, which made tuning bows a headache. Basically the synchronized cam system makes bows really easy to tune.

According to Darlington, one thing contributing to Darton’s accuracy is that their manufacturing process and specifications make each bow very consistent and easy to tune.

“That bow should shoot a bullet hole just by lining things up, and there shouldn’t be any more tuning than that to the bow,” he says.

Beyond the synchronized cam system found in almost every bow, many of the top bows had a wide limb stance.

“The limbs have gotten wider because it helps distribute stress and makes them less prone to fatigue. They hold up better,” Darlington says. “It also takes more effort to twist them, which makes the bow more stable.”

Bows used to have comfortable, but torque-prone, grips. These days more bows have a square, flat grip that promotes even and consistent grip pressure. There’s a reason target archers prefer a grip of that style, and bowhunters reap the same benefits. Another X factor is that there’s more archery information available. You can go to YouTube right now and get shooting advice from great coaches like John Dudley or George Rylas IV, and many bowhunters have. So you have fewer trigger slappers out there and more people shooting solid form. —S.E.

Why Modern Crossbows Aren’t More Accurate

While Darlington is known for his compound bow designs, Darton makes crossbows, too. Darlington provided insight into what’s holding back crossbow accuracy.

“The thing about crossbows is, if you take the arrow weight and you figure the amount of stored energy, it’s like shooting an under-spined arrow out of a compound bow,” he said. “So, you’ll encounter arrow flight issues you wouldn’t accept out of a compound bow.”

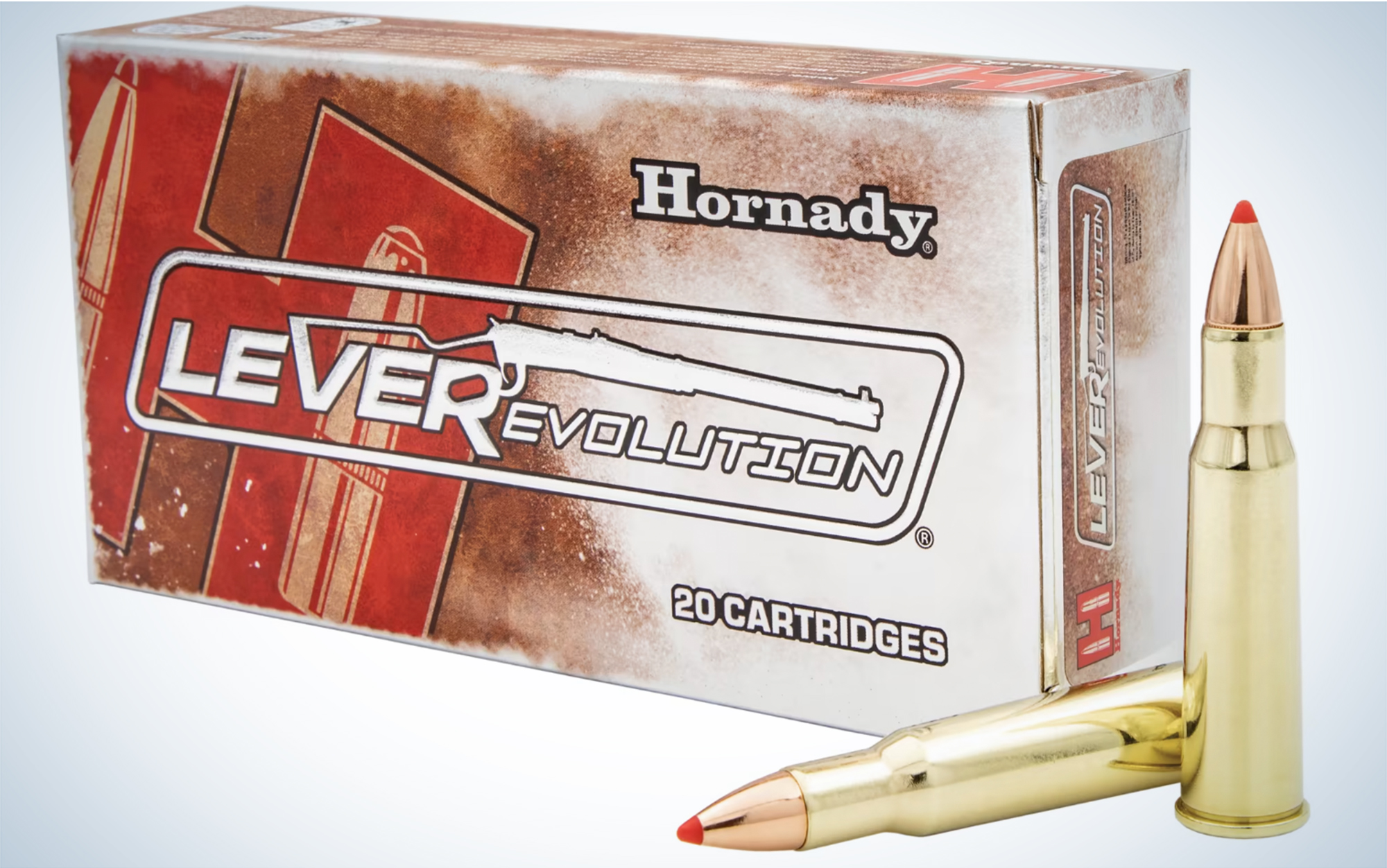

The issue isn’t the crossbow. It’s that the bolts they shoot aren’t optimized for their 300-pound draw weights. The result is the same as shooting a poorly-tuned compound bow. Another pitfall is some crossbow package bolts lack straightness and spine consistency. So, how do you get the most out of your crossbow? Tamp down the speed by shooting a heavier bolt or a crossbow with a lower draw weight.

“Mathews [Mission Crossbows] has pretty much dominated crossbow tournaments, but they’re not shooting very fast speeds out of their crossbows,” Darlington said. “Their weights are under 200 pounds and that’s one of the things that contributes to their accuracy.” —S.E.

Long-Range Accuracy

If we had stretched the range of our test to 70 yards or 100 yards, you’d see crossbow accuracy start to pull ahead of compound bow accuracy. Most average compound shooters would have a hard time turning in 6-inch or even 8-inch groups at 100 yards. Shooting from a supported position, with a scope, is too great of an advantage for all but the best compound shooters to overcome. But even with today’s, ultra-fast crossbows, 100 yards should not be considered a reasonable archery range. The bolt would be in flight for about three quarters of a second (more than enough time for the animal to move). Plus, at that range, wind can severely change a bolt’s point of impact. (I don’t know any average-joe crossbow hunters who have practiced enough with their setup to acquire accurate windage adjustments for 100-yard shots).

So while it’s true that crossbows are speeding ahead with innovations and incredible performance, when it comes to reasonable archery ranges, compound bows are just as accurate—and in the right hands, even more accurate. —A.R.

Crossbow Accuracy vs Compound Bow Accuracy Q&A

Are compound bows more accurate?

Yes, compound bows are more accurate than traditional bows and crossbows at moderate hunting ranges. That’s not to say that every compound bow is more accurate than every other type of bow. Only that the top-end compound bows are still more accurate on average (or at least easier to shoot accurately). And remember, the archer (not the bow) is always the most important factor in the accuracy equation.

What are the disadvantages of a crossbow?

Crossbows are loud and a bit unwieldily compared to compound bows. Plus, they can be difficult to cock while in a tree stand. However crossbows do have plenty of advantages over compound bows (see below).

Are crossbows easier to aim than bows?

Yes, crossbows are easier to aim because they have scopes and hold themselves at full draw. However shooting a crossbow offhand can be challenging. The best crossbow accuracy comes by placing the bow on a shooting rest, sticks, or the rail of a stand.

What are the advantages of a crossbow?

Modern crossbows are ultra-fast and relatively easy to use. Anyone familiar with shooting a gun can pick up a crossbow and shoot effectively at moderate ranges. Plus, crossbows remain cocked, so the archer doesn’t have to draw while the critter is in range.