The origin of mine warfare dates back all the way to the mid-19th century, during the American Civil War. In December 1861, Confederate officer Maj. Gen. Leonidas K. Polk oversaw several men as they loaded explosives into iron containers and buried them along two routes leading into Columbus, Ohio.

Luckily, the Union soldiers discovered the cache of explosives and dismantled them before they were detonated, but Polk and others had become infatuated with the idea of using mines to sway the outcome of the conflict in their favor. Half a century later, landmines took on a whole new level of lethality during the First World War and, in particular, the Battle of Messines.

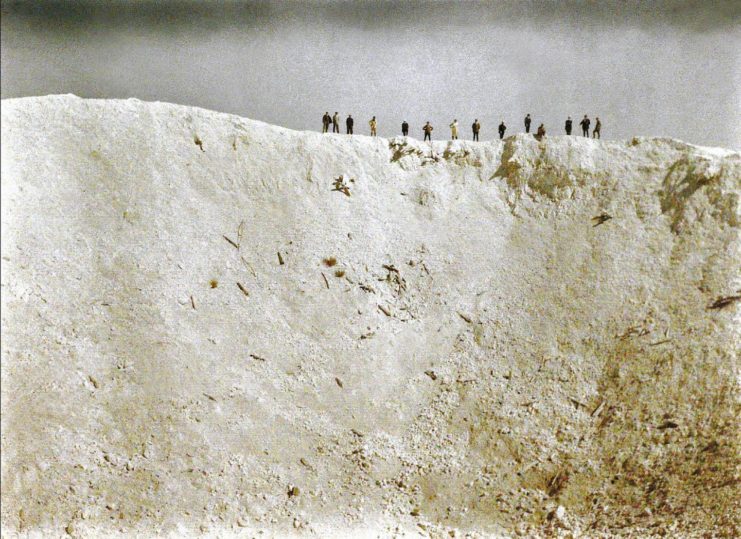

Planting Allied landmines along Messines Ridge

German forces came within meters of Allied mines

The Germans were also digging their own network of tunnels – in fact, one came within meters of the British mine chambers. They also unearthed a mine at La Petite Douve Farm well before the Battle of Messines began.

The Germans weren’t totally oblivious to the Allies’ mine plans, as spies and air-based reconnaissance had picked up on the heavy activity around Messines Ridge. They were also aware that the Allies were planning to use the mines as part of a ground-level attack. After debating leaving the area lined with mines, they decided an assault wasn’t imminent. If one happened to occur, they were confident enough in their defenses, even though some officers wanted to retire to a safer location.

Battle of Messines and the boom heard across Europe

Just before dawn on June 7, 1917, British artillery halted as the sound of nightingales singing broke through the silence of the battlefield. At 3:10 AM, the mines along the Messines were all fired within 20 seconds of each other, creating a massive boom as the largest non-nuclear explosion tore through German territory.

Some even suggested it was the loudest man-made sound in history, supposedly heard as far as London and Dublin.