As human population has grown over the centuries, so have the number of infectious diseases. Widespread trade routes, larger cities, an increase in population density, and new opportunities for human and animal interactions provided an ideal breeding ground for epidemics.

Diseases and illnesses have been a part of humanity since the dawn of mankind and the shift to an agrarian lifestyle created communities that increased the scale and spread of these diseases dramatically. In parallel with human development, the risk of epidemics has increased – malaria, tuberculosis, leprosy, influenza, smallpox, and other illnesses first appeared during this period.

An epidemic is when an infectious disease is rapidly spreading to a large number of people in a given population, for example, in a country. When a disease spreads beyond the border of countries, that’s when the disease officially becomes a pandemic.

Science distinguishes several pandemics that have decimated humanity throughout history. Some caused much greater damage than others, but which were the deadliest and how did we overcome them?

3. Spanish flu

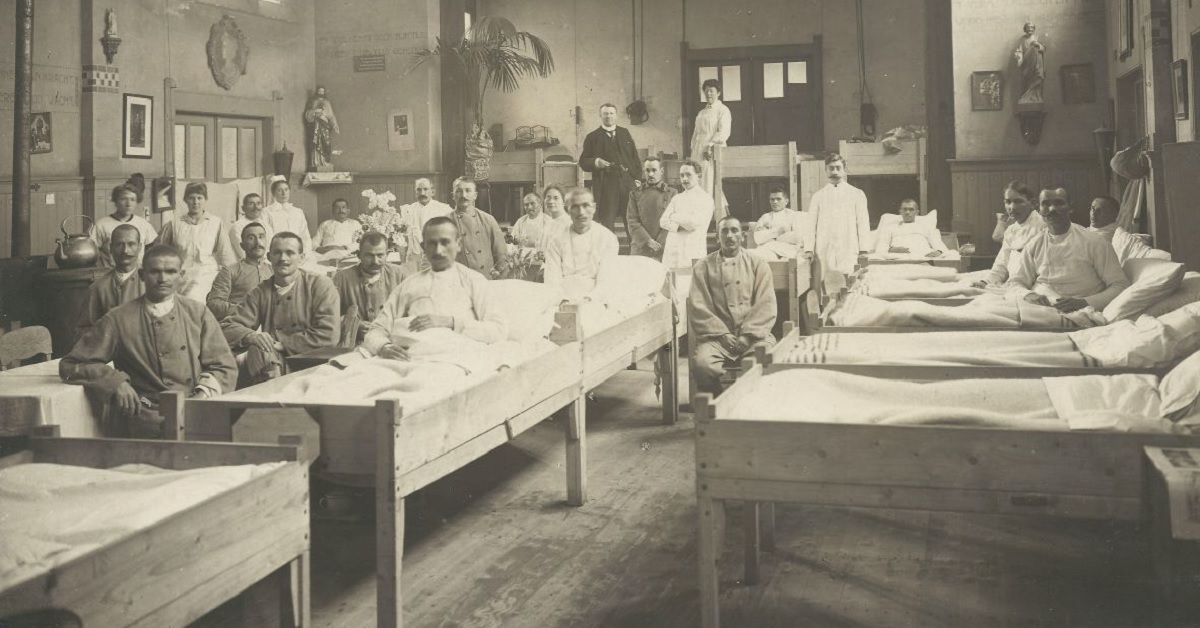

Lasting from February 1918 to April 1920, Spanish flu infected about a third of the world’s population at the time in two main waves. The death toll is estimated to be around 40-50 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics.

Many would think it got the name ‘Spanish flu’ because it originated in Spain, but the truth is that it was World War I, and to maintain morale censors minimalized the early reports of the flu, with Spain being the only country that was honest about the toll it took nationally. Hence, the common belief was that the virus hit Spain very hard and this gave rise to the name ‘Spanish’ flu.

The H1N1 influenza A virus, which caused the Spanish flu is a virus that attacks the respiratory system and is highly contagious. The first wave occurred in the spring of 1918 and was considered to be mild. People who got infected experienced typical flu symptoms, such as chills, fever and fatigue. They usually recovered after a few days and the reported death rate was low as well. However, a more contagious and deadly wave of the flu struck the world in the fall of the same year. The infected died within hours or days after developing symptoms, which were way more severe this time. First, dark spots appeared on their cheeks which spread across their face within a few hours. This was followed by a black coloration further spreading to their limbs and the torso. They would eventually suffocate from a lack of oxygen as their lungs filled with a frothy, bloody substance.

When the flu hit in 1918 there were no effective vaccines or drugs that could treat it and doctors were unsure what caused it or how to deal with it. Some communities shut down public places, introduced quarantines and ordered citizens to wear masks. People were also advised to avoid shaking hands and to stay indoors. Citizens in San Francisco were fined $5 (a lot of money at that time) if they were caught in public without masks and charged with disturbing the peace.

Although no treatment was available at the time, restrictions definitely helped to keep the mortality rate as low as possible. A good example of this is the case of Philadelphia and St. Louis. Not only did Philadelphia not close the public places, it even held a parade in the middle of the pandemic. The lack of protective measures against the flu resulted in 15,000 people dying in Philadelphia between September 1918 and March 1919. On the other hand, St. Louis banned public gatherings and closed schools and movie theaters. Consequently, the peak mortality rate in St. Louis was just 1/8 of Philadelphia’s death rate during the peak of the Spanish flu.

By 1920, the influenza virus came to an end, as those that were infected either died or developed immunity. The end of the pandemic didn’t result in a neat bookending, but society moved on. Many scientists believe that the flu viruses we deal with in recent times are directly related to the 1918 ancestor, even though a vaccine for both types A and B of the virus was developed in 1942. The 2009 flu pandemic vaccine provided some cross-protection against the Spanish flu pandemic strain as well.

2. Smallpox

According to the World Health Organization, smallpox terrorized the world for about 3000 years. The earliest evidence of the disease dates to the 3rd century BCE in Egyptian mummies. It spread from one person to another. The disease itself is caused by the variola virus, a member of the orthopoxvirus family, which also includes cowpox or monkeypox.

The early symptoms included fever and vomiting which was followed by ulcers in the mouth and a skin rash. The skin rash turned into the characteristic fluid-filled blisters in a couple of days, which eventually fell off with the end of the disease. Most people with smallpox recovered, but many survivors were left with permanent scars on their skin, and some became blind. The risk of death after contracting the disease was about 30%. Scientists believe smallpox was able to kill by crippling the immune system by attacking molecules made by our bodies to block viral replication.

The death rate in Afro-Eurasia paled in comparison to the devastation brought on native populations in the New World when smallpox arrived in the 15th century with the first European invaders to The Americas. The native population of Mexico and North America had no immunity at all to smallpox and it cut them down by the tens of millions. 90 to 95 percent of the indigenous population was wiped out over the next century.

By the mid-18th century, smallpox was a major endemic disease everywhere in the world except for Australia and small islands untouched by outside exploration. Smallpox was a leading cause of death, killing an estimated 400,000 Europeans each year in the 18th century throughout the continent. However, at the end of the 18th-century, a British doctor named Edward Jenner discovered that milkmaids infected with cowpox seemed immune to smallpox. Jenner famously inoculated his gardener’s 9-year-old son with cowpox and then exposed him to the smallpox virus which had no ill effect on him. With the discovery of Jenner, the first-ever vaccine was born. From there, countries launched massive vaccination programs and in 1980 the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated. It took two centuries after Jenner’s invention, but it paid off; smallpox became the first infectious disease in history that was eradicated with a vaccine.

1. Black Death (Bubonic Plague)

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that carved a path of death in Asia, Africa and Europe from 1346 to 1351. The pandemic claimed approximately 200 million lives in only 4 years, which makes it by far the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history.

The plague arrived in Europe in October 1347 when ships from the Black Sea docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. Many of the sailors aboard the ships were already dead. The few survivors were in critical condition; their bodies were covered in black boils that oozed blood and pus – the typical symptom of the bubonic plague. It was followed by a host of other unpleasant symptoms, such as fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, terrible aches and pains – then, in short order, death. People didn’t know what hit them, many believed it was God’s punishment for sins such as greed or blasphemy.

The Black Death killed 2/3 of Europe’s population and it may have reduced the world population from an estimated 475 million to 350–375 million in the 14th century. It took 200 years for Europe to regain the levels of 1300. The plague traveled from person to person through the air, as well as through the bite of infected fleas and rats – both could be found almost everywhere in medieval Europe.

The word ‘quarantine’ also originates from this period. In some coastal cities, officials implemented a 30 day isolation period for newly arrived ships, which was known as ‘trentino’. As time went on, the isolation period was extended to forty days, and given the name quarantino from the Italian word for 40.

Truth is that the plague never really ended and it reappeared every few generations for centuries. Although, none of the epidemics were as fatal as The Black Death. It is still present in some parts of the world, but you shouldn’t worry; standard sanitation practices greatly mitigated the impact of the disease and it can be easily treated with antibiotics.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10