The F-14 Tomcat was designed to defend the U.S. Navy’s fleets from practically every airborne threat. While it packed long-range AIM-54 Phoenix missiles for defense against bombers carrying standoff missiles, it was no slouch in a dogfight either, although early versions were held back by its TF30 engines in that arena.

But for a brief period in the 1990s, the F-14 was used as a strike aircraft. The Navy’s retirement of the A-6 Intruders left a small capability gap until the new F/A-18E/F Super Hornets entered service, and the F-14 could carry more bombs than the new F/A-18A/C Hornet.

Operations in former Yugoslavia and the Gulf showed the need for a heavy strike aircraft in the Navy’s arsenal. But how effective could the F-14 be in that role? While Israel used F-15B and Ds for ground strikes in relatively unmodified configurations, the U.S. Air Force spent a lot of effort developing a dedicated strike version of the F-15, the F-15E Strike Eagle. For the F-14, some small subsystems were installed, and the aircraft was sent on its way. Could it compete?

While the F-14 was only used operationally in the strike role by America in the 1990s, the aircraft was designed for it to a limited degree. Grumman showed the prototype carrying bombs, and flight tests were carried out with a rack of 14 Mark 82 bombs.

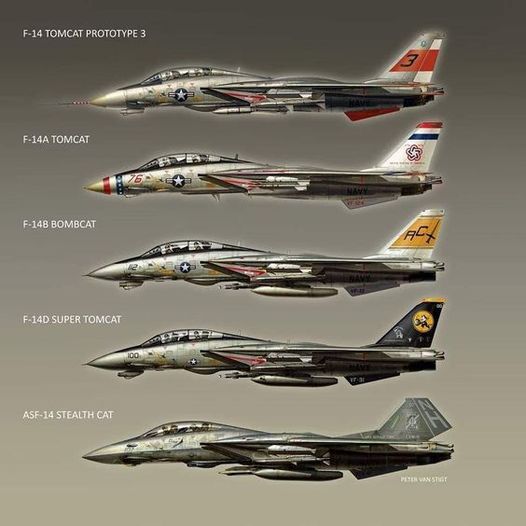

The F-14D, built with digital computers, expanded on this functionality: integrating more weapons onto the F-14. The F-14D was granted clearance by the Navy to drop bombs in 1992. However, it was the F-14B that would serve as the primary F-14 for ground attack.

The gap between the retirement of the A-6 Intruder in 1997 and the fielding of the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet in the 2000s let the Tomcat step up to the plate as a ground attacker. Anticipating the shortfall in capability, a Navy paper in December 1994 urged the acquisition of targeting pods so that Tomcat could fulfill this role.