We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The .220 Swift is odd. It has world-beating velocity, but never became widely popular among hunters. It is a load we all should have fallen in love with—since it’s the fastest commercial rifle cartridge in the world—but didn’t.

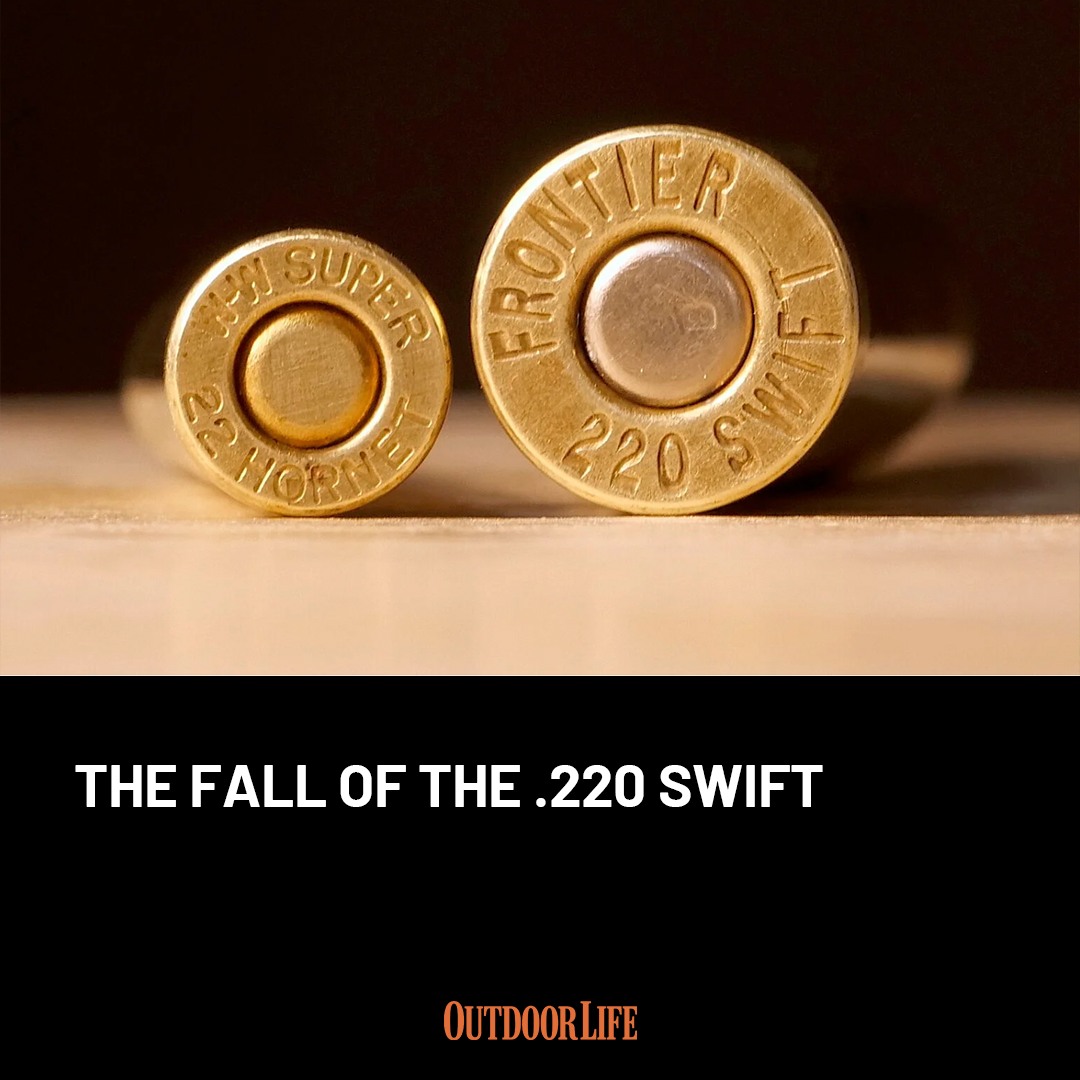

The .220 Swift is a .22-caliber round that fires .224-inch bullets, the same as used atop .223 Remington, .22-250 Remington, .224 Weatherby Magnum, .24 Nosler and similar .22 centerfire cartridges. Winchester created this load, and named it for what it was—swift.

It’s a “hot” round, pushing a 48-grain bullet at 4,100 fps. The .220 Swift was faster than any other commercial cartridge of any other caliber in the world (and still is). Only the .204 Ruger comes close to the .220 in terms of speed. The .223 WSSM could match the .220 in velocity, but that cartridge is now obsolete.

It was built pre-WWII, before fighter jets had been invented or the atom had been split. The next fastest .22-caliber rifle cartridge extant at the time, the .22 Hornet, pushed 40-grain bullets about 1,400 fps slower than the .220. It was so advanced that 86 years later nothing has caught up in terms of speed (the .22 Savage Hi-Power of 1912 drove 70-grain bullets about 2,800 fps, but they were .228 inches).

So why isn’t the .220 a popular load for today’s hunters and target shooters? There are a few different reasons. But first, let’s take a closer look at the history of the .220 Swift, and its ballistic makeup. Then I will delve into why it failed.

Building the Fastest Rifle Round

How did Winchester pull this off? They went to the Navy for the .220 Swift’s parent case. From 1895 to 1899 the U.S. Navy was experimenting with a straight-pull bolt-action rifle built by Winchester chambered for 6mm. That round burned the then new smokeless powder to push a 112-grain round nose bullet 2,560 fps. To stabilize that, rifling twist was a surprisingly fast-for-the-era (and still today) 1:7.5 inches.

While the 6mm Lee Navy cartridge and rifle was accurate and dependable, both were phased out in favor of the .30/40 Krag, which was itself dumped for the .30/03 three years later. Three years after that the .30/03 was jettisoned for the .30/06.

Winchester sold a few straight-pull rifles and its 6mm Lee Navy ammo for many years, but lever-actions were all the rage. Bolt-actions and 6mm calibers were a trifle too esoteric for the average American hunter. With the languishing 6mm cartridge in its portfolio, Winchester had the foundation and incentive to reformulate it. But instead of sticking with the 6mm, a lonely caliber at the time, Winchester decided to squeeze in .224 bullets.

In that era the .22 Hornet was making waves, so wildcatters were beginning to stuff its little bullets atop other cases in an effort to gain more speed. Woodchucks, ground squirrels, foxes, crows, and hawks were a ubiquitous menace around farms and ranches across the country. “Varmints” were a genuine threat to chickens, sheep, and daily dinners, if not livelihoods. A .22 with more reach than the Hornet was needed, and the .220 Swift delivered in spades. It shot flatter at 325 yards than the Hornet at 230 yards. And delivered 725 foot-pounds more energy.

The Swift Shoots Like a Laser

From the get go the Swift was controversial. Winchester chambered it in its 26-inch barreled M54 bolt-action, a precursor to the M70 that appeared two years later. Of course, it was lauded as the new super-cartridge, able to travel 300 yards in record time. Had there been such a thing as a laser, the Swift’s trajectory would have been favorably compared. Woodchucks began having their garden depredations short-circuited while still 400 yards away from the carrots. Whitetails and mule deer collapsed at the touch of the little 48-grain projectile to their ribs. More than a few westerners found it effective on elk and at least one adventurer applied it successfully to a tiger in India. By the mid-20th century noted gunsmith P.O. Ackley was touting the .220 Swift as “the greatest one-shot killer on deer and similar game ever produced.”

But there were detractors. The one with the loudest megaphone was one of the most recognized writers of the time, Robert Ruark. He escorted a .220 Swift to Africa, wounded a hyena with it, and declared he wouldn’t even use the hot .22-caliber “on a woodchuck.” “Use enough gun” became his rallying cry. In contrast, Lester Womack, who was culling destructive feral burros in the Grand Canyon region in 1948, discovered the .220 Swift dispatched 600-pound burros more effectively than the .30/40 Krag, .30/06 Springfield, and 8mm Mauser used by fellow cullers out to 600 yards. As if that weren’t astonishing enough, Womack compared the impact of his .220 Swift 48-grain factory loads to a .270 Winchester 100-grain load, and .30/06 armor-piercing military bullets.

After a decade working with the .220 Swift as well as many other cartridges, Mr. Womack declared: “If I were forced to choose only one rifle from my rack and forsake all others, the choice would be simple — I would reach for the .220 Swift.” Womack was shooting Winchester’s 48-grain bullets, but also 50-grain Ackley Controlled Expansion all-copper bullets with 10 grains of lead in the nose cavity.

The Unpopular .220

That rifleman’s declarations notwithstanding, Ruark’s opinion stuck, augmented to no small degree by complaints of severe throat erosion and early barrel burn out by many high-volume varmint shooters. Handloaders complained of case stretching and a frequent need to trim for case length.

In response to these complains, it is said, Winchester and other ammomakers began reducing .220 Swift muzzle velocities, but the barrel burner rumor mill wouldn’t stop churning. Then the .22-250 Remington hit the market in 1965, driving same-weight bullets as the Swift, but about 200 fps slower. That was fast enough for most. The .22-250 took off and left the speedier Swift in the dust.

Today, most riflemakers chamber for the .22-250 Remington and .223 Remington, but almost none make a rifle for the Swift. Nevertheless, the speed king remains the ultimate, high-velocity .22. It’s also as accurate as or slightly more accurate than, on average, the .22-250 Rem, according to records kept by some gunmakers and many serious varmint hunters who work with both. The steels in modern barrels have reduced the throat burning significantly, too. Many .220 Swift shooters report stellar accuracy after 2,000 rounds, some 2,500 rounds. The trick is to temper the rate of fire.

Read Next: 13 of the Biggest Gun Fails in Recent Firearm History

The .220 is the Ultimate Coyote Load

The .220 Swift’s biggest problem results from its 19th century heritage. It sports a rare “semi-rim,” a concession to its parent’s use in a military machine gun. By today’s standards it has excessive body tape and a sloping shoulder of 21 degrees, a far cry from the 30- to 35-degree shoulders preferred on modern, long range cartridges. The upshot is a bit more case stretching, which leads to frequent neck trimming.

Despite this, most handloaders can get five to eight reloads from a Swift case depending on how hot they load.

Twist rates in most factory-built .220 Swift rifles are 1:14, a few are 1:12. Neither is fast enough for traditional bullets heavier than 60 or 62 grains, which can be pushed to 3,712 fps from 26-inch barrels. The more common 55-grain loads should hit 3,850 fps, about 100 to 200 fps faster than the .22-250 Remington pushing the same weight, and 600 fps faster than the .223 Remington.

The overall cartridge length of the Swift is 2.680 inches, leaving it plenty of room to fit in standard short-action magazines (2.8 inches), even with today’s longer high B.C. bullets. Given the Swift’s powder capacity, this seems an excellent option for increasing its versatility. A 1:8 twist custom barrel and long-throat chamber will be required to handle the longer bullets, but muzzle velocities as high as 3,350 fps, perhaps 50 fps more, should be easily attained with 75-grain bullets. Couple that with the .220 Swift’s famous precision and you’re looking at extraordinary long range performance and minimal wind deflection with a .224 bullet. With a 1:7 twist the Swift will stabilize 90-grain bullets and drive them at least 3,000 fps for additionally impressive long-range performance.

What’s the 220 Swift good for? Besides long-range rodent control work, it could be considered the ultimate long-range coyote cartridge. In states where .22-calibers are legal for big game it’s been a proven killer on pronghorn, whitetails, and mule deer. In an 8-pound rifle, recoil energy is just 7 foot-pounds with 7.5 fps recoil velocity. That makes it a fine option for ringing steel at distance. Just pace yourself and the .220 Swift will keep you on target for thousands of rounds.