:focal(638x478:639x479)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/90/43/90436ed6-ddc7-4a99-a361-7d836187bab5/covers2.jpg)

Jewish Museum Berlin / Curt Bloch collection / Charities Aid Foundation America

For two years during World War II, a Jewish lawyer named Curt Bloch lived in an attic in the Netherlands, hiding from the Nazis. He received water, food and essentials from his hosts, as did thousands of other Jews hidden in similar circumstances.

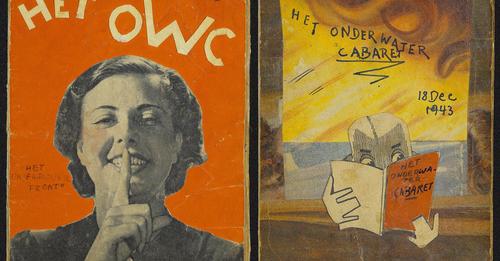

But Bloch’s protectors also provided him with newspapers, pens, glue and other supplies. Each week, he used those materials to create a new issue of his own satirical magazine: Het Onderwater Cabaret. Next month, its 95 issues of art, poetry and song will go on display in “‘My Verses Are Like Dynamite’: Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret,” a free exhibition at the Jewish Museum Berlin.

Bloch’s work was previously “almost completely unknown,” as curator Aubrey Pomerance tells the New York Times’ Nina Siegal. “The overwhelming majority of writings that were created in hiding were destroyed. If they weren’t, they’ve come to the public attention before now. So, it’s tremendously exciting.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9a/c1/9ac19f0e-b9fb-4339-b403-cd70a5047a8b/owc_cover_1943-30-08_downloadimage.jpg)

Jewish Museum Berlin / Curt Bloch collection / Charities Aid Foundation America

Born in Dortmund, Germany, in 1908, Bloch was working as a legal clerk when Adolf Hitler became the country’s chancellor in 1933. Spurred by Hitler’s antisemitic rhetoric, anti-Jewish violence escalated in Dortmund, and after one of Bloch’s coworkers threatened him, Bloch moved to Amsterdam. Come 1940, he was working for a Persian rug business, hoping to move farther west, when Germany invaded the Netherlands. Bloch was transferred to the Hague, then to the small city of Enschede, where he began working for a local Jewish council.

In 1943, with the Nazis closing in and deportation to concentration camps looming, the council urged its members to go into hiding. That spring, Bloch moved into the home of Aleida and Bertus Menneken, a housekeeper and an undertaker, where he shared a small attic with two other Jews, according to Artnet’s Jo Lawson-Tancred.

His hiding place was arranged by Group Overduin, an organization of roughly 50 members who helped at least 1,000 Jews hide from the Nazis, per the Times. The group was founded by Leendert Overduin, a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church, who was ultimately arrested and imprisoned for his efforts. In 1973, Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance center, named him Righteous Among the Nations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/90/58903b1a-303b-402f-beff-924d9f336ccc/owc_cover_1944-16-09_downloadimage.jpg)

Jewish Museum Berlin / Curt Bloch collection / Charities Aid Foundation America

In the attic, Bloch began his magazine, Het Onderwater Cabaret (or The Underwater Cabaret). Inspired by a German radio program called the “Sunday Afternoon Cabaret,” the title used “a unique term in Dutch for the act of going into hiding: ‘onderduiken,’” writes the Times. “Its literal translation is ‘to dive under,’ but a common translation is ‘to slip out of public view.’” Between August 1943 and April 1945, he created a pocket-sized issue every week.

In each issue, Bloch wrote about “the crimes of the Nazis and their collaborators, the course of the war, his situation in hiding, the fate of his family and the approaching defeat of the Axis powers,” according to a statement from the museum. He often targeted Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels, writing in one poem, “If he writes straight, read it crooked. / If he writes crooked, read it straight.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2a/09/2a098dfb-43fe-4769-92cd-d7f0aa2fe7ac/pressebild_curt_bloch_portrait.jpeg)

Jewish Museum Berlin / Lide Schattenkerk

Bloch’s covers—often displaying the magazine’s abbreviated title, Het OWC—incorporated images cut from newspapers and magazines. Dutch author Gerard Groeneveld, who published The Underwater Cabaret: The Satirical Resistance of Curt Bloch last year, tells the Times that the covers were inspired by other anti-fascist satirical magazines, like Germany’s Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (Workers’ Illustrated Magazine).

Though Bloch had to remain hidden, his publication didn’t. Groeneveld estimates that the magazine had 20 to 30 readers, perhaps including other Jews in hiding.

“There was [a] huge organization behind him, which included couriers who brought food, but who could also bring the magazine out, to share with other people in the group who could be trusted,” says Groeneveld to the Times. “They must have also returned them in some way.”

Bloch and his roommates survived in the attic until the spring of 1945, when Germany surrendered. With the liberation of the Netherlands, Bloch was free. Most of his family, however, had died in the Holocaust. In 1946, he married a fellow survivor, Ruth Kan, and in 1948 the two immigrated to New York, where they raised two children.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/19/ba1950c6-dd89-4010-a3da-690d5b83c245/owc_cover_1945-03-04_downloadimage.jpg)

Jewish Museum Berlin / Curt Bloch collection / Charities Aid Foundation America

Their daughter, Simone Bloch, now 64, tells the Times that her father would occasionally read from Het Onderwater Cabaret, but she couldn’t understand German as a child. Much later, Simone’s daughter, Lucy, embarked on a research journey to study the documents’ history, which led to Groeneveld’s book and the upcoming exhibition.

After Bloch was liberated from the Dutch attic that had held him for two years, he created a final issue of Het Onderwater Cabaret in April 1945. Its cover depicts two individuals emerging from a hatch, with the title declaring that they were at last “above water.”

“‘My Verses Are Like Dynamite’: Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret” will be on view at the Jewish Museum Berlin from February 9 to May 26.