To this date, the oldest genomic data recovered was from a horse found preserved in the Canadian permafrost dating to 780–560 thousand years ago. This has now all changed.

An international team led by scientists at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm has sequenced DNA recovered from the remains of three ancient mammoths, one of which had been buried in the Siberian permafrost for about 1.2 million years, or more. By analyzing the DNA the researchers were able to turn around the earlier assumption that the iconic Columbian mammoth evolved before the smaller, shaggier woolly mammoth and revealed a new lineage in the mammoth family. The findings were published in Nature.

While two of the three mammoths are over 1 million years old and predate the existence of the woolly mammoth, the third speciman is about 700,000 years old and represents one of the earliest known woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius). The genetic material was acquired from their teeth.

“This is – by a wide margin – the oldest DNA ever recovered,” Professor Love Dalén, study author from the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm said.

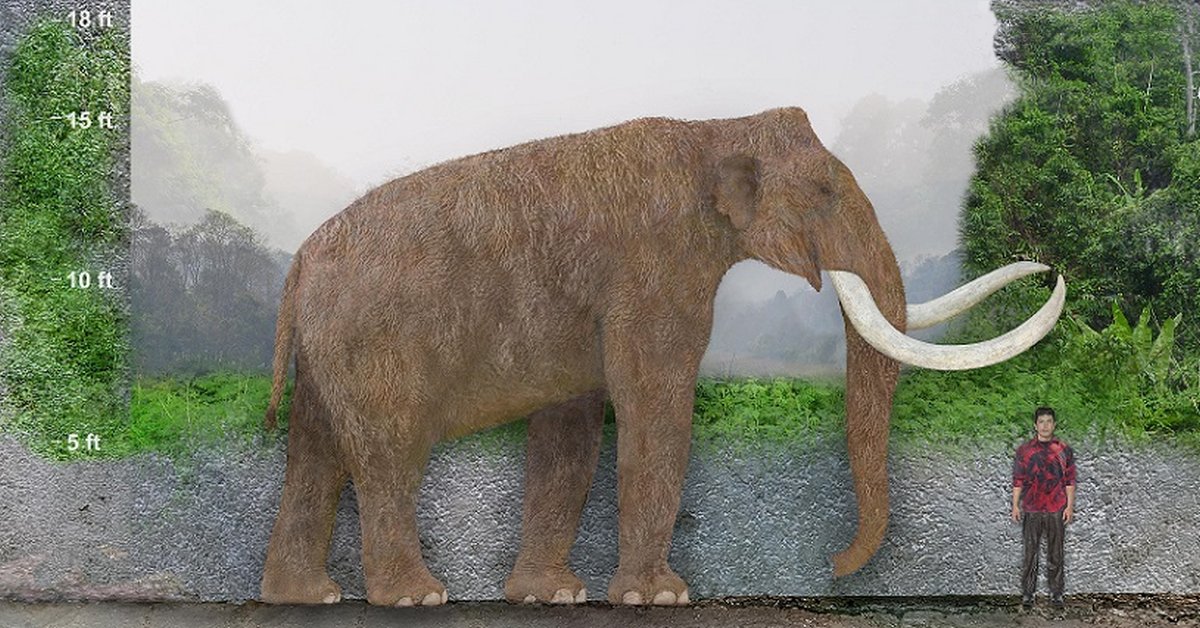

The second oldest specimen is an ancient steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii), a direct ancestor of the woolly mammoth and perhaps the largest species of mammoth and one of the largest proboscideans. The massive steppe mammoth was up to 15 feet tall and weighed about 12 – 14 tonnes. It is among the largest land mammals that ever lived.

Even more interestingly, the oldest specimen the scientists studied belongs to a previously unknown genetic lineage of mammoth, now referred to as the Krestovka mammoth. The scientists conservatively estimate it to be 1.2 million years old – that is the age of the geological section in which it was found. However, mitochondrial genome data indicates this specimen could actually be up to 1.65 million years old, while the second (steppe) mammoth could be 1.34 million years old.

The analyses show that the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) that inhabited North America during the last ice age was a hybrid between the woolly mammoth and this previously unrecognized genetic lineage of mammoth.

It wasn’t an easy feat for the scientists involved to get those results, however, as the genome of these prehistoric mammals has seen much better days, to put it mildly. In fact, it has become so extremely degraded over the millennia that instead of a nice long strip of flawless genetic material, the research team was confronted with billions of odd, miniscule fragments of DNA, which they had to put together meticulously, much like a game of puzzle.

“We have many, many small puzzle pieces and we’re trying to reconstruct the puzzle. The small piece you have, the harder it is to reconstruct the whole puzzle,” explained lead study author Dr Tom van der Valk.

The team set off by extracting a bit of material from the interior of each mammoth tooth with a small dentist’s drill. Then they applied chemicals and enzymes, followed by a washing protocol, to isolate the DNA from the resulting tooth powder.

Most of the extracted DNA consisted of sequences as short as a few dozens of base pairs. (A base pair is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids that contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA.)

To make matters worse, many of the puzzle pieces they came across were not even the mammoths’ but belonged to bacteria or fungi that have contaminated the sample. Luckily, the team had high-quality genomes of woolly mammoths and present-day elephant relatives to use for reference.

When the researchers had managed to eliminate all the non-mammoth DNA, they were left with between 49 million and 3.7 billion base pairs in each of their three samples. (Slightly larger than the human genome, the mammoth DNA is built up of roughly 3.2 billion base pairs.) At this point, the researchers compared their data with elephant DNA a second time, which allowed them to put all the recovered DNA fragments in the correct order.

With the new results at hand, the team believes it’s theoretically possible to recover DNA that is even older than the one recovered from these mammoths. That said, since no permafrost on the Northern Hemisphere is older than 2.5 million years, recovering DNA beyond that time may prove extremely difficult, if not impossible, noted the researchers. Of course, even this “limited” timeframe means a lot to discover, especially as these new insights are gained.

“It’s quite possible that, in the future, the methods will be there to recover DNA from human non-permafrost specimens that are close to 1 million years old,” speculated Professor Dalén.

We can’t wait to see and report on the results of that new quest for scientific knowledge – if it ever happens, of course.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6